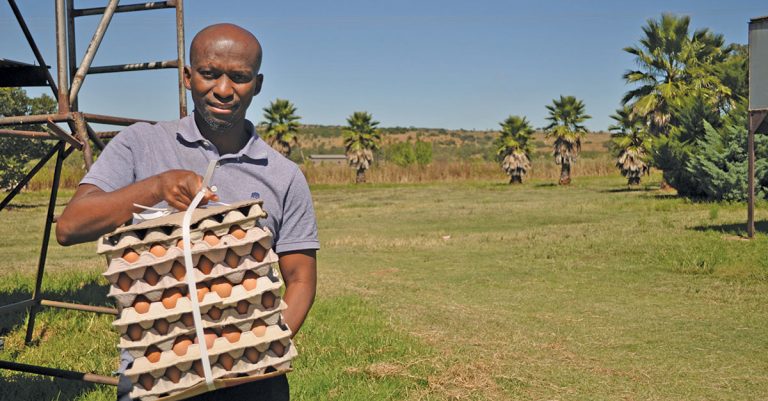

Photo: Pieter Dempsey

When Kobedi Pilane started farming in 2009, he had 2 000 broilers, as well as a few pigs. Although he had no formal training or background in farming, he did have experience in running a business, which equipped him with many of the skills needed to run a successful farm.

He has also learnt much over the past 10 years or so by seeking help and advice from other producers. In 2017, Pilane purchased a 43ha farm, Brakfontein, near Parys in North West, after getting a loan from the Land Bank. At the same time, he made the switch from broiler farming to egg production, starting out with 3 800 layers.

His flock has since grown to 5 000 layers and his goal is to double this to 10 000 over the next few years, provided he can get the necessary funding.

Production and housing

Pilane’s farm has two poultry houses that can house 2 000 and 3 000 layers respectively. There are also two 18t silos in which feed is stored. He buys in Lohmann point-of-lay pullets and is in the process of increasing the productivity of the flock.

The hens currently lay at a rate of around 700 eggs per 1 000 chickens per day but, ideally, he would like to increase this to between 800 and 870 eggs.

The chickens are housed in a battery-caged system designed according to industry standards, and the cages are cleaned daily. Pilane monitors the feed intake and productivity of the chickens so that he can maintain proper production records.

“The layers are culled after about 56 weeks, by which time they should have laid at least

265 eggs each. There is a mortality rate of about 4%,” says Pilane.

Taking into account mortalities and the layer replacement rate of 12,5%, the facility maintains an efficiency rate of about 83%, which means that when the farm is at full capacity with 5 000 layers, it can produce up to 4 150 eggs per day.

“On average, the layers stay on the farm for between 56 and 70 weeks, after which they are sold on the meat market. I sell up to 400 chickens a month, and replace them at the same rate.”

Production management

Pilane has not implemented formal biosecurity measures on the farm due to the cost of implementing such a system, but he does implement control measures such as restricting movement on the farm.

The layers are fed a ration mixed according to a set formula to ensure sufficient calcium in their diet. Pilane goes through 18t of feed in about six weeks during summer, and five weeks in winter when the layer houses are at full capacity.

The point-of-lay pullets arrive on the farm when they are about 17 weeks old, and start laying after a week or so.

The temperature in the houses is kept at between 25°C and 30°C by manually raising or lowering the curtains on the sides of the houses to control airflow.

The birds are vaccinated when they are purchased, which includes vaccines for bursal disease and Marek’s disease.

They are treated preventatively on a monthly basis for ailments such as Newcastle disease and bronchitis. The chickens are also regularly given a stress pack, consisting of a soluble form of vitamins and electrolytes, through their drinking water; this benefits production immensely, says Pilane, as there is always a drop in the number of eggs laid when chickens suffer from stress.

This could be brought on by any of a number of reasons, including a change of season from summer to winter, or an altered feed formula.

“I plan to implement a biosecurity protocol in the future to prevent any subsequent outbreaks of diseases on the farm,” he says.

Marketing and expansion plans

Pilane says he was able to grow his flock from 3 800 to 5 000 layers rapidly because of the demand for eggs on the informal and formal markets that he supplies.

Although the demand from the informal market is strong, he prefers to also have formal supply agreements in place to ensure a secure market for his eggs. He has offtake agreements with Mugg & Bean and Wimpy, whom he supplies with eggs on a weekly basis, and the remainder of his eggs are sold out of hand and to the informal market. All of these markets are within a 100km radius of the farm.

His future expansion plans all hinge on whether or not he receives the funding he has applied for. According to Pilane, it is very challenging to grow the business because of the very low profit margins, which are affected by the high cost of feed.

“If my funding is approved, I’ll be able to turn this farm around to ensure it remains profitable,” he says.

Diversification

Pilane is currently moving to a new farm that will afford him the opportunity to increase his production as well as diversify by planting crops that he can use to produce his own feed for the chickens.

In addition to the funding that he is trying to secure, he is investigating an opportunity to become a majority shareholder in a broiler farm in the area that has the capacity to produce 250 000 chickens.

“Diversification is key. This is why I’m also focusing on sheep production now to provide an additional source of income for the farm,” he says.

Email Kobedi Pilane at [email protected].