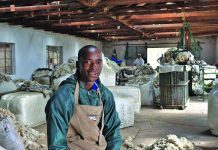

Photo: Glenneis Kriel

Since they started farming Angora goats at Amantis Landgoed in 2014, Jasper and Leon van der Westhuizen have broken the world record for the price of a bale of adult mohair several times, ending 2021 with a bale that fetched an astonishing R620/kg.

Their 400ha farm near Mossel Bay produces an average clip of 26mm, which is the industry standard for young goats.

Jasper says that Angora goats are not a popular choice with farmers in the Southern Cape, as they are difficult to manage, often escaping from their camps. Coming from the Karoo, however, he and Leon were used to farming Angoras, and see these goats as the future of livestock production.

“The demand for renewable and natural fibres is increasing. This is especially the case with fibres like ours, which are produced in an environmentally and ethically responsible manner, as underlined by Responsible Mohair Standard certification. Mohair is also highly versatile, with textile and industrial applications,” he says.

Good genetics

The Van der Westhuizens ascribe their success with Angora goats to good genetics, sound management practices, and a favourable production environment.

“When we started farming Angoras, we built the herd on a solid foundation by buying the best genetics we could afford from Fred and Billy Colborne, stud breeders in Willowmore. It’s tempting to save money by buying cheap animals, but this will negatively affect your bottom line in the long run, as it can take years to correct problems through selective breeding,” says Jasper.

Today, the brothers have no need to buy in new ewes, and simply replace one or two rams every year, depending on demand. “We make use of natural breeding techniques, with one ram used on every 30 ewes,” says Leon.

The 220 ewes they bought from the Colbornes averaged between six and seven years of age which, in the Karoo, is considered past an Angora goat’s prime. Jasper explains that goats typically start to lose their teeth from this age, resulting in dietary problems that negatively affect their health, reproduction and mohair quality.

The softer veld grasses of the Southern Cape, however, are much gentler on the goats’ teeth than Karoo bushes, and this greatly increases the longevity of these animals. The result is that some of their original ewes are still going strong in their herd, even without teeth. On the downside, the veld grasses of this area are not as nutritious as Karoo bushes, so the goats have to be fed daily to maintain their condition, which significantly increases production costs.

“We buy all our feed from a reputable source, De Heus, with whom we’ve built a relationship over the years, and try to plant barley when there’s sufficient soil moisture. Unfortunately, this has been more the exception than the rule, as our farm has been subjected to drought since we bought it in 2014,” says Jasper.

Leon would like to plant lucerne once they have broken out of the dry cycle, at least in the camps used for weaning. “The drought and rising input costs are threatening our sustainability and make mistakes very costly. For now, it’s better to stick with what we know than to try out new things,” he says.

Feed management

The dietary plan for the goats has been designed by a feed specialist and is continually adjusted according to the animals’ condition, their reproductive cycle, climatic conditions, and the condition and availability of veld and planted pastures. Liver examinations are also done on dead animals to identify mineral and vitamin deficiencies.

“Feeding is one of the cornerstones of livestock production, as it directly influences the quality of fibre, offspring and reproduction. It doesn’t pay to have the best genetics if you’re not feeding your animals well,” says Jasper.

The ewes are given high-protein rations for two months, from just after weaning until the mating season starts, to ensure that they are in optimal condition when placed with the rams. Once they have conceived, they receive high-energy rations for good foetus development and to prevent abortions, low birthweights and poor lactation.

The ewes are also given premixed multivitamins and minerals, as well as phosphate, in their feed and licks to prevent nutritional deficiencies.

“I prefer licks over products mixed into the feed, as the intake of weak animals can be negatively affected by competition at feeding troughs. Intake is restricted when a lick is used, which helps to equalise intake among the animals,” says Leon.

Angora goats can tolerate some heat stress, although it results in lower feed and higher water intake. Problems occur when the temperature fluctuates greatly and conditions are cold, wet and windy.

“We put the goats in a shed for protection when we expect cold and windy conditions, and supplement their water with glucose to prevent their blood sugar from falling, which can cause them to go into shock and even die,” he says.

He adds that giving the goats a balanced ration throughout the year and keeping them in a good condition make them less vulnerable to stress and diseases.

Production management

The Van der Westhuizens place the ewes with the rams in April to ensure that the kidding

season starts towards the second week of September, after the wet and cold winter conditions in the region.

The ewes are dewormed and vaccinated two to three weeks before the breeding and lambing seasons start, during which time they are also injected with a multivitamin mineral supplement.

“Our wet conditions favour the development of intestinal parasites, such as roundworm and hookworm, especially when warm days are followed by very wet conditions. Where Karoo farmers can get away with one anthelmintic treatment a year, we give regular treatments guided by climatic conditions and animal observations,” says Leon.

As a preventative measure, the drinking and feeding troughs are kept clean to prevent a build-up of parasites. “This is actually non-negotiable, no matter where you farm,” he stresses.

The brothers’ dosing and vaccination protocols are based on industry advice and the newsletters of Dr Mackie Hobson, veterinarian at the South African Mohair Growers’ Association.

The ewes are taken to smaller camps a week before kidding; afterwards, they are placed in small pens with their offspring for two to three days, during which times they are closely observed so that problems can be addressed before they get out of control.

The ewes with their offspring, along with other ewes and their kids, are then moved to a small camp, where they stay for at least five days before being reintroduced to the big camps.

“Most kid mortalities occur during the first two weeks after birth. Time in the pens and smaller camps enables us to intervene quickly when problems arise. It also strengthens the bond between the ewes and their kids, which in turn helps prevent later complications, such as a kid not being able to follow the ewe or a ewe losing its kid,” says Leon.

So far, their ewes have produced only single kids, but this has been under drought conditions.

“While it’s good to have twins, their management is more difficult, as the ewe needs to be strong enough to raise two kids,” he says.

Shearing

The goats are sheared in August, about three weeks before the lambing season starts, and again in February, two weeks before the kids are weaned.

“We keep the kids with the ewes for about 22 weeks, which is longer than the norm. This, and not shearing during weaning, helps to significantly reduce weaning shock,” says Leon.

It is also easier to castrate young rams after they have been sheared. The rams are separated from the ewes and kept on lower-quality veld after weaning. “We keep the young rams separate from the older rams during the first year to prevent them from being bullied,” says Jasper.

The goats are shorn in a shed, but there is not enough space for all of them during shearing. This means that if it rains, they have to be moved to prevent their hair from getting wet. Fortunately, due to the relatively small size of the herd, shearing can be completed in about four days. The goats’ hair is shampooed and conditioned before shearing.

The shearing team grades the hair, but the Van der Westhuizens spend up to six weeks thereafter sorting it. “We find that agents go out of their way to get you a good deal when they see you put effort into supplying them with a high-quality product,” says Jasper.

The goats are not crutched, as the farm is far from shearing teams. Contrary to expectation, however, this has not had a big influence on the quality or colour of their fleece, according to Leon.

The shearers also clip the hair on the goats’ heads (‘wigging’), to prevent ‘wool blindness’.

“If you leave the hair over their eyes, the goats won’t be able to see where they’re going or where their food and water are.”

None of the animals on the farm is culled, unless the quality of its hair starts to deteriorate.

“We’re in the business of mohair production, so we keep animals as long as they produce good-quality hair, regardless of their age or whether they’re good or bad mothers,” says Leon.

Email Leon or Jasper van der Westhuizen at [email protected], or [email protected].