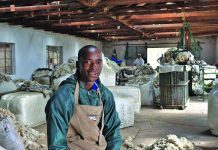

Photo: Annelie Coleman

It all began with wattle. Stan Burger had vast quantities of the unsightly weed covering his game ranch, Iwamanzi, near Koster in North West.

His solution was to introduce a flock of Damara sheep to fight the invasion, and eight years later he has become passionate about the breed, arguing that it is uniquely adaptable, economical and profitable.

READ Preventing disease in goats and sheep

More significantly, Stan, who is today president of the South African Damara Breeders’ Society, is determined to preserve the breed, ensuring its characteristics are maintained.

One of the Damara’s chief advantages is its non-selective feeding habits. Damara sheep graze grass and forbs (40%) as other sheep do, but also browse (60%) in a similar fashion to goats.

The anatomy of its rump allows Damara sheep to stand on their hind legs like a Boer goat. Moreover, these ‘sheep-goats’ have a particular fondness for wattle, a fact that Stan has used to his advantage.

“They eat virtually anything and have, to a great extent, annihilated the wattle,” he explains.

“They literally eat it to death, browsing on the leaves and shoots as soon as they emerge. And because they can reach shoots high up, they’re very efficient feeders. They consume the wattle seedlings entirely. They also browse sickle bush and even enjoy milkweed, which is highly toxic but seems to have no effect on them.”

Natural selection

The indigenous Damara sheep are highly adaptable and selected by nature for exceptional fertility and foraging ability. The breed originated from wild Asian sheep such as the Moufflon, Argali and Urial and its ancestors entered Africa through Europe, moving south along the east coast of the continent.

It reached Southern Africa some two thousand years ago, where it spread to northern Namibia and the southern parts of Angola. Commercial farmers in then South West Africa obtained the sheep from the Himba people in the 20th century.

Stan explains that only the fittest survived this epic migration.

READ Goat breeding: the challenges faced by smallholders

“Nature is a ruthless selector and only the hardiest and most adaptable animals made it, retaining the essence of the breed’s gene pool,” he says.

“The onus now rests on Damara breeders to preserve its pure genetic base. This is a highly economical and profitable breed that’s ideal for today’s sheep farming with its ever-increasing input and production costs.”

Naturally selected to deal with extremes, Damara sheep were, for example, generally unaffected by the recent Rift Valley fever epidemic.

Stan’s 200-strong Rubicon Stud is run free-range on the 3 700ha game farm along with buffalo, blesbok, sable, wildebeest and zebra.

The veld has a carrying capacity of 5ha/MLU, with an average annual rainfall of between 600mm and 800mm. Temperatures range from -5°C to 40°C.

“The only additional feed my sheep get is chocolate maize or lucerne to entice them into the kraal at night,” says Stan.

“The Damara is a natural free-range forager, as one can see from its strong legs. It is less dependent on water than other breeds, which means it can range widely.”

Disease-resistant

According to Stan, the Damara is “virtually unaffected” by internal and external parasites.

“This makes it the ideal breed for me, because heartwater and gallsickness are endemic here,” he explains.

“My disease management programme consists of a weekly foot dip and I treat the groins and legs once a month against ticks. I apply the pesticides by hand and use a variety of ecologically friendly products.”

Stan selects animals with a high degree of natural resistance to internal parasites, and points out that the breed’s distribution is now from the Kalahari to Alldays and even in the subtropical areas of Tzaneen and KwaZulu-Natal.

This is due both to its strong resistance and its effectiveness in combating invasive vegetation and indigenous bush encroachment.

The formidable Damara

The Damara’s alert nature and strong flocking instinct ensures that the lambs stay well-protected against predators such as black-backed jackal, claims Stan.

“I’ve seen my flock standing its ground against two black-backed jackal, the big rams on the outside and the young protected inside the flock,” he says.

“The Damaras’ horns make them a formidable quarry for predators. We do kraal them at night for protection against larger predators such as brown hyena and leopard, though.

“The flocking instinct also makes life difficult for stock thieves. It’s one thing to steal a few sheep, but a different ball game with an entire flock.”

Efficient breeding

According to Stan, the production characteristics of Damara have improved to such an extent that, coupled with exceptional feed conversion, the breed performs on a par or even better in harsh conditions than exotic sheep breeds.

“The days when the Damara was referred to as the breed with four shoulders are long gone. It performs strongly under extreme conditions, while the so-called superbreeds do well only under ideal conditions,” he explains.

In addition, Stan has found that although the Damara’s carcass is relatively light, the breed’s production per hectare is high, thanks to high lambing and weaning rates, strong maternal behaviour and early maturation.

He says that his ewes can be mated at 30 to 36 weeks, with first lambing at 52 to 58 weeks and an average inter-lambing period of 30 to 34 weeks. Multiple births are common and an annual flock lambing rate of 140% is the norm under favourable conditions.

In addition, low mean lambing weights of between four and four-and-a-half kilograms mean few lambing problems.

The ewes have a reproductive lifespan of between eight and 13 years due to their strong, well-developed teeth, among other factors. Rejected lambs are rare, thanks to the ewes’ strong maternal instinct.

According to Stan, the average live weight of an adult ram is 80kg to 95kg while the average ewe weighs 50kg to 65kg. The average 100-day weight is 21kg to 26kg, the average six-month weight is 32,5kg and the average 12-month weight is 46,6kg.

“The meat is juicy, tender and lean because most of the body fat is stored in the tail.

“An added bonus is that Damara skins are graded as glove quality and obtain high prices. The skin is currently still sold as part of the so-called fifth quarter at abattoirs, but I want to explore this further,” he explains.

Affordable

Stan believes that the Damara, with its affordablity, low input costs and ease of care, is the ideal option for commercial as well as developing farmers. Registered ewes can be bought for between R2 000 and R2 500. Registered rams sell for R5 500 to R15 000 and both ewes and rams have become sought after for crossbreeding.

“Damara is the breed of the future,” Stan concludes. “Its mutton is healthy, gourmet-quality meat, free from antibiotics and other additives and will become increasingly popular as consumers strive for a healthier diet.”

Email Stan Burger at [email protected].