Photo: Glenneis Kriel

Developing a production calendar can be a daunting task, as there are so many variables to consider. The trick is to keep it simple, and that’s exactly what Dr Danie Odendaal, founder and director of the Veterinarian Network (V-Net), has done with the V-Plan herd management plan, which he has designed and improved over the past 30 years.

According to Odendaal, his V-Plan is based on two essential principles:

- Livestock have a specific reproductive cycle that must be maintained and optimised to unlock the full income potential of a herd/flock.

- Seasonality affects feed availability.

Beef cows have a gestation period of nine months and are dry for three months before

being impregnated again, whereas sheep have a gestation period of only five months.

In the past, sheep were left to recover for seven months before being placed with rams again; these days, most farmers have shortened the recovery period after lambing to three months. In these intensive breeding systems, sheep reproduce every eight months, or three times over a two-year period.

DOWNLOAD Herd health and production management calendar for livestock

Odendaal says a few farmers are shortening the recovery after lambing to two months, but he advises against this, as it requires extraordinarily intensive feed management and takes a toll on ewes and their offspring in the long run.

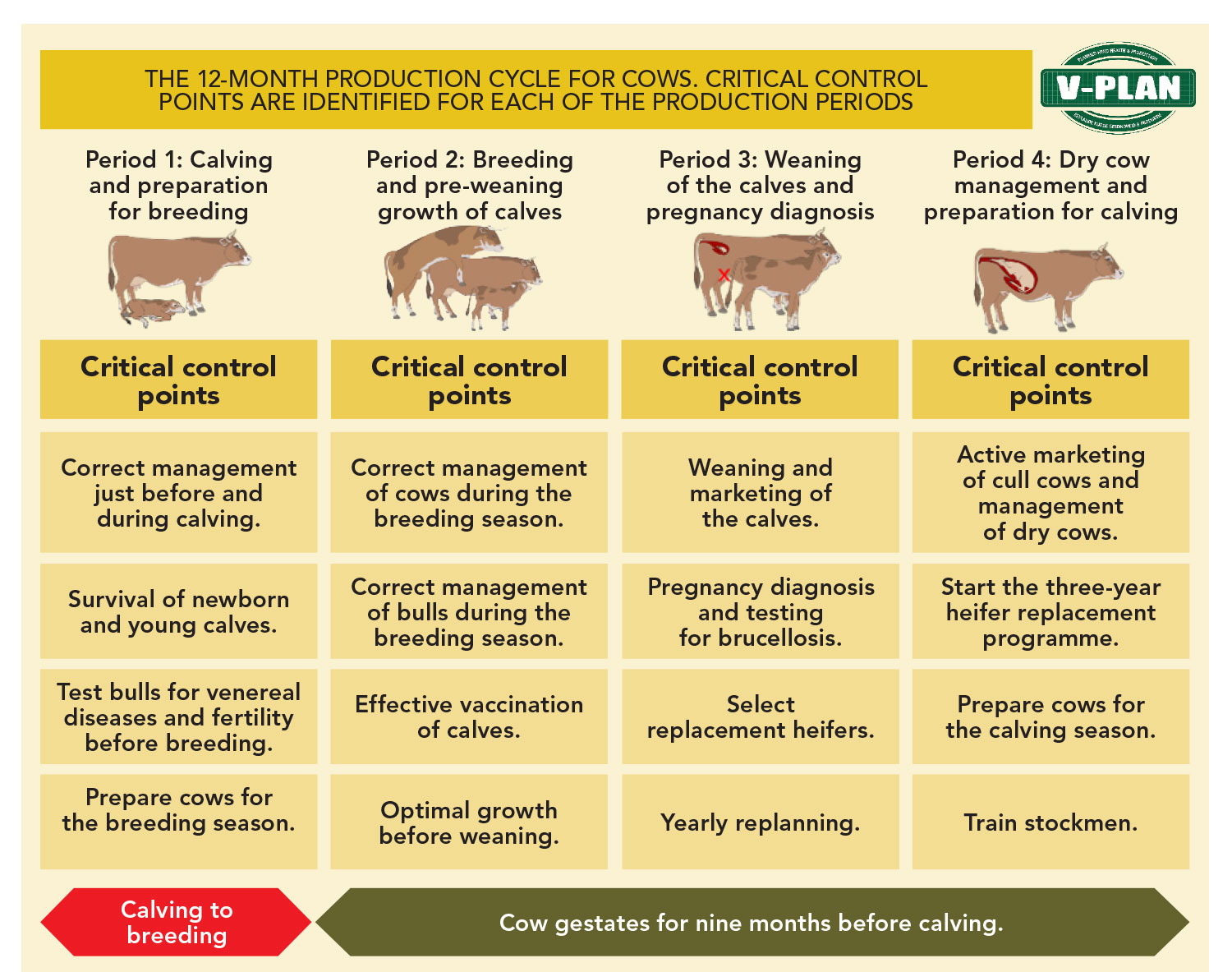

The reproductive cycle can be divided into different stages, based on changes in the animals’ dietary needs, management and health requirements; these stages are calving, mating, weaning and, for cows, the dry period. For cows, each of these stages will be, on average, three months long within a 12-month production cycle.

With sheep, there are two stages: lambing and mating. The period between stages will differ from three to seven months, depending on the intensity of the production system (one lambing season per year or three in a two-year cycle).

The seasonality of production

Odendaal says it is important to break production down into these stages, because the dietary requirements and the way in which the animals should be managed differ greatly from one stage to another.

The protein requirements of a cow after calving, for example, are approximately double that required after weaning, because she needs to produce milk and get back into condition before being placed with the bull.

Turning to the second principle that the V-Plan is based upon, in summer rainfall areas, veld becomes less palatable and its nutritional value can drop by half in winter, whereas it is the other way around in winter rainfall areas.

“Some people argue that the seasons don’t really matter, as you can feed livestock year-round,” says Odendaal.

“But this isn’t cost-effective and is unsustainable in the long run. So once you’ve broken production down into its various stages, match these with the seasonal availability of feed.”

The seasons also influence outbreaks of pests and diseases. These are usually a bigger problem during wet seasons, with significant population booms observed when extreme dry conditions are followed by very wet seasons, as is currently happening.

In summer rainfall areas, lice in late winter and ticks, worms and flies during summer might affect the condition of the animals and lead to disease. Livestock should therefore be inspected weekly and dipped when high loads of ectoparasites are expected.

“External parasites may cause various fatal diseases, most of which are incurable but can be prevented by vaccination,” notes Odendaal.

“So don’t take chances; ensure your animals are up to date with their vaccination programme.”

The time of vaccination will depend on the product. Your veterinarian can help you to develop a programme that addresses the main threats in your area. More than 200 veterinarians participate in the V-Net disease reporting system, providing a monthly report of disease cases and outbreaks.

Practical implementation

Odendaal has developed a chart (see tables) that farmers can use to develop a herd health and production management calendar for their livestock. The farmer, in consultation with his/her herd’s veterinarian, starts by filling in the month when the mating season starts and works out the critical actions and production protocols from here.

“For each stage, the farmers and their vets can identify certain critical management outcomes and then define specific management actions or protocols and the steps that should be taken to achieve these,” says Odendaal.

He identifies the birth season as one of the most critical stages of production, as most calf and lamb mortalities take place within the first 10 days after birth.

“Some farmers regard the death of a newborn as of little concern. But the truth is that you’re losing at least R7 000 in terms of the sales value of a weaner and at least R3 000 in terms of the cost of bringing a cow to term. That money is lost; it cannot be replaced.”

In short, do your very best to limit mortalities during the birth season. To begin with, move gestating animals to predetermined camps a few weeks before they give birth. The camps should have enough feed and water, and be sheltered from extreme weather and predators.

While animals should generally be checked weekly, they should be checked daily during the birthing season to identify and address problems before they get out of control.

Train your stockmen well to ensure they have the skills to deal with complications before the season starts.

“Many stockmen these days didn’t grow up with livestock, so need to be trained to identify birthing signs, understand the normal birthing process and deal with complications,” says Odendaal.

“Cows, for instance, usually take two hours to give birth after their waters break, whereas the time can be four hours with heifers. Intervention is needed if it takes longer.”

Steps to take in the event of birth complications should also be clearly stipulated. For example, if a calf is stuck with its feet next to its head, the legs should be pulled straight and the face pushed back to straighten the elbows and facilitate normal birthing.

If one leg is stuck, the stockman should act quickly and use gloves and lubricant to straighten this leg. If both legs and not the head can be seen, it is an indication that the head is turned backwards and stuck. Tie a rope to the legs and push the calf back to reposition it.

Each protocol should also stipulate what needs to be done if an intervention does not help. Odendaal says the best course is to phone the vet within 30 minutes.

Ensure that sheep and calves get sufficient colostrum as soon as possible after birth; this will boost their immunity and help their intestinal development.

Immunity wears off after a while, so calves and lambs should be vaccinated against diseases prevalent in the area from three months of age, as advised by the herd vet for the specific farm and production system.

“Consult your vet to help you develop a vaccination programme for 12 months ahead and to inform you when certain disease risks develop in the area. This 12-month vaccination plan forms the cornerstone of planned herd health. Prevention is always much better and cheaper than cure,” says Odendaal.

Female animals should be evaluated to ensure they have enough milk and can look after their young. The offspring should also be evaluated to check whether they are gaining enough weight.

Give creep feed to get the young animals used to it, stimulate their stomachs and reduce their dependence on their dams for sustenance over time. This will also help to ease weaning shock.

Weaning and dry season

During the weaning stage, take great care to ensure optimal growth of the young animals. In addition, start making plans for the marketing of animals that will not be incorporated into the herds.

“Cull and replace old female animals and those that didn’t raise offspring or those that experienced complications. You cannot afford to keep freeloaders in a herd,” says Odendaal.

Internal and external parasites should be monitored and managed to prevent them from turning into a problem.

Depending on the parasite load and time of year, ewes and cows might have to be dipped and dewormed a month before the mating season to ensure they are in good condition and able to carry and raise their offspring. Give top-up vaccinations before the mating season starts, as many vaccines cannot be given to gestating animals because of the risk of abortion.

Ewe and ram feed should be supplemented to ensure they are in good condition when

the breeding season starts.

“Look at what’s available in the veld and talk to a livestock nutritionist to help you provide the correct supplement to balance the nutrition available from grazing,” says Odendaal.

“Female animals should have a body condition of at least 2,5 when the mating season starts. If they’re too fat or too thin, they’ll struggle to conceive or won’t be in a good enough condition to look after their offspring.”

It is better to keep female animals in as a good condition as possible throughout the reproductive cycle, because it’s difficult to improve an animal’s condition in only a few months before mating.

During this stage, pay special attention to addressing nutritional deficiencies. Trace minerals and vitamins A and E are especially important, according to Odendaal, as they can have a positive effect on conception and help limit embryo losses.

Bulls and rams should be evaluated, tested and exercised to ensure they are in peak condition when the mating season starts.

Mating season

During the mating season, be sure to implement the correct male:female ratio, and observe the animals to ensure the males are working. Take immediate action if you see any problems.

The female animals should be scanned a few weeks after mating to identify animals that did not conceive and need to be serviced again, and those that are carrying multiples and therefore require more feed to maintain their condition.

Separate the animals into groups according to the results.

Protein levels in the female animals’ diets should also be increased to accommodate the growth of the foetuses and ensure that the gestating animals have enough milk to support their offspring by the time they give birth.

Odendaal says the whole goal of a production calendar is to ensure the optimal production of offspring per female animal.

“To achieve this, you need to take the right action at the right time, which means adjusting the feed regime according to the changing needs of animals during different productive stages and taking actions, such as vaccination and biosecurity measures, to prevent diseases as far as possible.”

Email Dr Danie Odendaal at [email protected].