When Dr Faffa Malan, Prof Gareth Bath, and Prof Jan van Wyk first introduced FAMACHA (short for FAffa MAlan Chart), they gave sheep and goat farmers something they had long needed: a simple way to spot animals that were suffering from anaemia caused by wireworm, also known as barber’s pole worm.

By using the chart, farmers no longer needed to routinely drench their entire flocks. Instead, they could check the mucous membrane of each animal’s eye, compare its colour to that on the chart, and only give extra treatment to the animals that genuinely needed it.

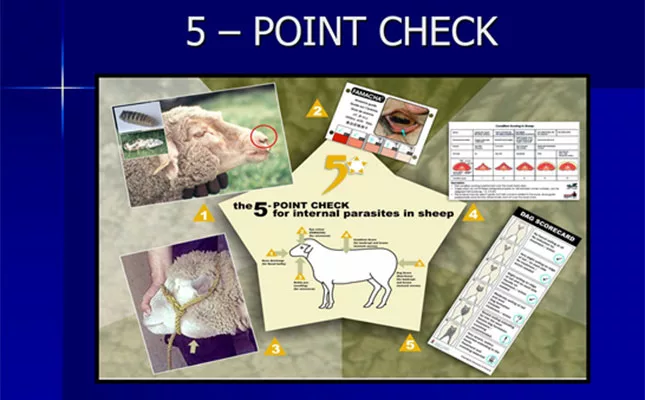

Malan says FAMACHA was a tremendous breakthrough, but Bath took it even further by developing it into the Five Point Check.

“The Five Point Check broadened the focus beyond anaemia to other visible signs of parasite problems and has since revolutionised parasite control around the world through its enabling of selective treatments,” he explains.

He warns, however, that farmers should not see FAMACHA and the Five Point Check as replacements for veterinarian-developed worm management programmes but rather as tools to complement them alongside good grazing practices to help prevent and reduce worm-resistance issues.

From chart to full-body check

With the Five Point Check, farmers are encouraged to regularly examine the eyes, nose, jaw, tail, and back of each animal to identify parasite or disease problems.

The eye check is where FAMACHA comes in. By pulling down the lower eyelid and comparing the colour of the mucous membrane with what’s on the chart, one can tell whether the animal is anaemic.

Those with pale membranes, falling into categories three to five, are considered at risk and should be treated on the advice of a veterinarian.

The nose is checked for discharge, which may signal nasal botfly, lungworm, or pneumonia.

The jaw is checked for swelling of the soft tissue, referred to as ‘bottle jaw’, which may indicate wireworm, liver fluke, hookworm, or conical fluke. The tail is checked for soiling, which might indicate bankrupt worm, conical fluke, brown stomach worm, nodular worms, and other worms.

The backs of goats and sheep are evaluated to determine their body condition, as poor body condition may indicate brown stomach worm, bankrupt worm, long-necked bankrupt worm, nodular worms, tapeworms, and other worms.

Malan says farmers should consider that the list is largely confined to internal parasites, although the causes of animals being flagged may be much more diverse and include diseases and nutritional imbalances or deficiencies.

The tell-tale signs might also be masked. Eye membranes, for instance, may appear redder than they should be because of irritation caused by dust, closed sheds, hot conditions, fever, eye infections, and diseases associated with blood circulatory failure.

“The best thing to do is to consult your veterinarian to help you identify the exact cause and best remedy for the situation under your production conditions,” he adds.

Evaluations and treatments

Malan advises farmers to check sheep, especially lambs and in-lamb or lactating ewes, every two to three weeks during the high worm risk period and as often as weekly at the peak of the worm season.

“Warm and wet conditions are usually associated with outbreaks in the summer rainfall area, but you should also familiarise yourself with what is happening on other farms in your region to identify other potential risks,” he says.

In large flocks, it can be time-consuming to check every animal at every inspection. In those cases, a smaller group of around 50 can be checked as a sample.

If most of the animals in the sample look strong and healthy and none fall into the danger zones, it is safe to assume the rest of the flock is coping. But if even one is severely affected, or 10% to 20% fall into the middle category, it is safer to check the entire flock.

Whole-flock treatment might be necessary at times. For example, if more than 10% of animals fall into the severe risk category, it may be better to dose all of them or move them to a fresh camp if grazing conditions allow.

Once an animal is treated, it needs to be marked with an ear tag or other visible marker, so it’s easy to track how often they need treatment.

An animal that needs more treatment than most of the flock is a red flag.

“The reasoning is simple: sheep that cannot cope with worms will pass weak genetics to their offspring. Removing them strengthens the flock over time,” he explains.

Importance of refugia

Another key principle, Malan adds, is refugia, which refers to the portion of the worm population left untreated. These worms are assumed to be mostly susceptible to treatment, helping to dilute resistant ones.

“If every single worm is exposed to a drug, only the resistant survivors will breed. Refugia slows this process down by ensuring resistant worms are mixed with susceptible ones, so the resistant population does not take over,” he explains.

Farmers can maintain refugia by avoiding whole-flock treatments unless they’re absolutely necessary, treating only the animals flagged by the Five Point Check, and returning treated animals to already contaminated pastures rather than clean ones during treatment.

Grazing management

But treatment and refugia alone are not enough. Grazing management plays a crucial role in controlling parasite pressure. The longer the animals remain in one camp, the higher the level of contamination becomes as larvae build up over time.

Heavy grazing pressure adds to the problem, with many animals confined to small areas quickly turning pastures into hotspots of infection, which should be treated to prevent future contamination.

Time away from a camp reduces these risks. “The longer a camp, veld, or enclosure is rested, the lower the risk,” explains Malan.

Alternating grazing between different species, such as cattle or ostriches after sheep, also helps break the worm cycle.

Pasture type and condition further influence risk. Short grazing exposes animals to more larvae, which are concentrated near the soil surface. Dense, matted grasses like kikuyu favour parasite survival, while herb-rich pastures are generally safer.

Flat, marshy areas and south-facing slopes are cooler and wetter, creating favourable conditions for worms, and irrigation can aid the survival of larvae on pastures.

Final advice

Farmers should also ensure that animals do not suffer from any diseases or nutrient imbalances that might cause stress and negatively impact their ability to deal with worms effectively.

Additionally, dung samples can be taken to identify pasture contamination and therefore risks, as well as drug-resistant worms.

Along with this, newly introduced animals should be quarantined and treated with the best drug available to minimise their risk of introducing drug-resistant worms to the rest of the flock. They should be checked for faecal egg count after 14 days and only be released from quarantine if they are clear.

Malan’s closing message is clear: smart parasite control is about more than just treating disease. It’s about monitoring animals carefully, consulting veterinarians, managing grazing effectively, and culling persistently weak performers.

“By using the Five Point Check wisely, farmers can protect their flocks, cut costs, safeguard the effectiveness of medicines, and build stronger, more resilient animals for the future,” he concludes.

Click here for more information on FAMACHA.