Fertility is five times more financially important to the beef producer than growth rate, and 10 times more important than carcass quality.

This is according to the authors of the highly regarded textbook, Animal Sciences: The Biology, Care, and Production of Domestic Animals.

Calving rates are the best and most commonly used parameters to gauge reproductive performance of cows or a herd. Although data is limited, research by veterinary surgeon, Dr Laetitia Gaudex, of Gaborone, suggests that average communal calving rates in Africa are 34% to 40%.

Her study details the average calving rates in various areas within South Africa, as well as elsewhere on the continent. It shows that, while the South African commercial sector boasts among the top calving rates (61%), the communal sector is far lower at only 23%.

Venda communal farmers achieve calving rates of only 15%, based on their responses to questionnaires.

Wild fluctuation

Data from southern Ethiopia shows a calving rate average of 55%, but this fluctuates between 12% and 83%. Zambia’s calving rate ranges from 44% to 80%, based on questionnaire responses, while Mazvihwa in southern Zimbabwe recorded a range of 68% to 82% (based on 12 years of data).

In most African countries, between 60% and 80% of rural households keep livestock as mobile assets, income generators and for household food security and nutrition.

According to a 2012 Food and Agriculture Organization report, smallholders provided up to 80% of the food in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

However, if Africa is to play its part as the ‘future breadbasket of the world’, the productivity and output of the livestock sector will have to increase drastically.

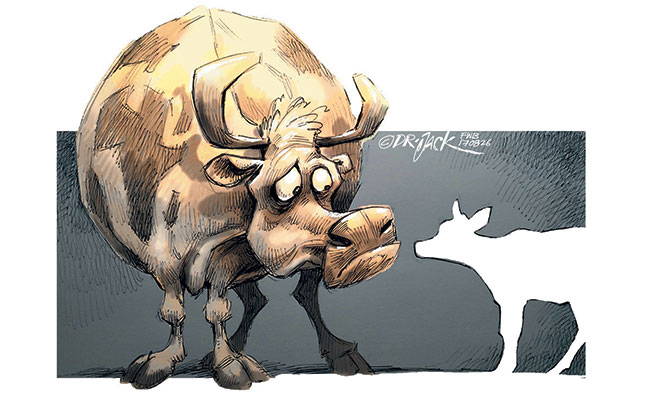

It cannot afford to have, on average, six out of every 10 cows as non-productive ‘passengers’ on grazing lands, particularly when droughts are becoming more and more frequent.

Moreover, if management and observation are lacking, calving rates can be misleading, as possible losses of newborn calves, for whatever reason, might be missed.

Root causes

A 2004 study conducted by Mokantla et al into the reasons for low calving percentages in communal cattle in Jericho in North West, found that low calving rates could be attributed mostly to poor bull fertility, poor nutrition (overgrazing and lack of supplementary feeding), diseases causing foetal loss, mismatches between herd genetics and the environment, and seasonal environmental stresses such as droughts, severe winters and high environmental temperatures.

According to a 2014 livestock futures study by the UN, Africa is the continent where ‘sustainable intensification’ of agriculture and livestock systems could achieve significant benefits.

These include food security, increased sustainable incomes for smallholder farmers, higher net food exports and trade balance deficit reduction, smallholder competitiveness and ecosystem services.

Sustainable intensification would require, inter alia, the increased provision of services, inputs, appropriate institutional support, and market/value chain development.

These are all essential to making livestock operations more viable, but they remain mere jargon at a macro level if something concrete is not done at grassroots level. It is here that we need to be changing the lives and productivity of communal and smallholder farmers.

In other words, when it comes to calving rates (and, indeed, other aspects of production), we need to stop talking and start doing!

Rolling up our sleeves and getting on with the job

Every role player within the support structures (government, NGOs and the private sector) should do something practical and positive every day towards achieving the aforementioned goals.

- Examples include:

Providing livestock owners and handlers across Africa with training on primary animal health care, livestock management and production. - Giving farmers affordable access to crucial inputs such as vaccines, supplements and medicines. This means breaking down bureaucratic red tape barriers and ensuring regional harmonisation of regulations to make registrations faster and cheaper.

- Creating a systematic programme of school-farm projects (farm-in-the-box solutions) to expose the youth to farming, create a passion for it among them, and teach them the economics of profitable farming from a young age.

- Not a single agribusiness conference or workshop should be conducted without a clear set of practical goals. Furthermore, these must be based on achievements or lessons learnt, reported on a country-by-country basis at next year’s Agribusiness Africa Conference.

- Low calving rates are but one symptom of reduced production capacity on the continent. If we don’t find solutions by 2030, Africa might not be able to feed itself. The current nearly 400 million undernourished people in Africa would probably having doubled again by then.

The continent would also not be able to contribute to food security for the rest of the world, as is envisioned, and it would fail in achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals set for 2030. It would be unable to become a net exporter of food and would instead remain a net importer. In turn, this would result in continual growth of trade balance deficits.

Blink of an eye

Africa would also fall behind in the endeavour to achieve environmental sustainability and climatic resilience. And if animal health is not taken seriously on the continent, there is the added risk of exposing the human population to devastating zoonotic disease threats.

We need to realise very soon that food production across the world, including Africa, must double in a mere 33 years. It took approximately 4 000 years of accumulated knowledge and skills in agriculture to achieve our current level of food production; we now have just over three decades to double that ability.

In the context of the long history of agriculture and the growth of the human population, that’s the mere blink of an eye!

Sources: Gaudex, L. 2014. ‘A health and demographic surveillance system of cattle

on communal rangelands in Bushbuckridge, South Africa: Baseline census and population dynamics over 12 Months’. MSc Animal Health. University of Pretoria: South Africa; Campbell, JR et al. 2003. Animal Sciences: The Biology, Care and Production of Domestic Animals. Waveland Press: US; Mokantla, E et al. 2004. ‘An investigation into the causes of low calving percentage in communally grazed cattle in Jericho, North West Province.’ Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 75[1]; Herrero, M et al. 2014. African livestock futures: realizing the potential of livestock for food security, poverty reduction and the environment in sub-Saharan Africa. Office of the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General for Food Security and Nutrition and the United Nations System Influenza Coordination.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Phone Dr Riaan du Preez on 012 817 9060, or email him at [email protected].