A statue of Paul Kruger stands tall and proud in Church Square in Pretoria. If he were still alive, he might stand tall and proud outside his farmhouses at Boekenhoutfontein beyond Rustenburg in North West – they still pretty much look how they would have when he lived there in the 1860s and 1870s.

Kruger still elicits mixed opinions more than 100 years after his death, but the legacy of his farmhouses, in the grounds of the Kedar Heritage Lodge, is solid. They point to the modest lifestyle of those early Boers: peach-pip and cow-dung floors, corrugated iron or thatch roofs, small rooms, simply decorated, thick mud-brick walls and small windows.

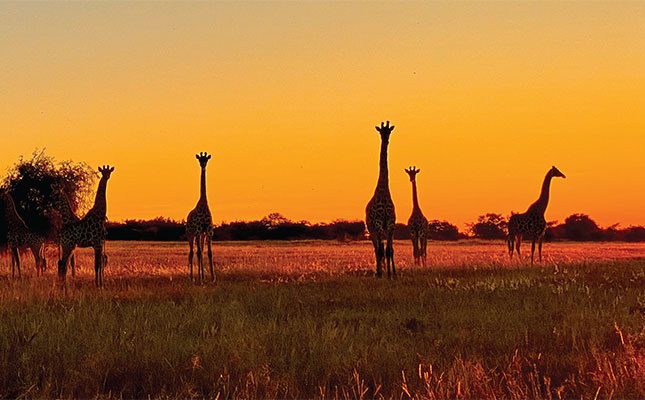

They are on land some 20km north-west of Rustenburg, a game reserve of 500ha with giraffe, wildebeest, eland, blesbok, waterbuck, zebra, and more. Hunting is offered at the lodge, and for South African War history enthusiasts, cabinets bursting with war memorabilia.

Kruger’s small tin bath sits in the foyer, a tight fit for him. Game drives, two restaurants and a spa complete the picture of a relaxed stay in the bushveld.

There are four farmhouses on the site, tucked against the koppie of scattered thorn and boekenhout (beechwood) trees. The first one, built by Rudolph Bronkhorst, now called the Bronkhorst House, is a simple three-room structure of mud brick and thatch roof, built sometime after 1840, when the first Voortrekkers reached the then Transvaal.

Kruger bought this house in 1862 but soon built his own house alongside it. It’s an attractive whitewashed house with thatch roof, consisting of several rooms, with its original peach-pip and dung floors. It now acts as a museum, packed with artefacts and farm implements.

As his family grew, Kruger built a bigger home, this time in the Georgian style, familiar to him from his childhood in Colesberg. It’s a double-storey house with a flat roof and flat facade. The ground floor contains three bedrooms, a voorkamer, dining room and kitchen.

The house contains period furniture, and the kitchen is filled with 19th-century ware. A steep stairway leads to the top floor, used as a storeroom. It’s a pleasing, homely house, with wallpaper in the dining room and blue walls in Kruger and his wife Gezina’s small bedroom, the colour believed to repel mosquitoes.

The fourth house on the site is in typical Victorian style, with a front stoep running its length and finished with a wooden balustrade. It is closed at the moment as funds are needed to renovate it.

This house was built by Kruger’s youngest son, Pieter, who also built the schoolhouse next to it, a long hall structure, now with wooden benches and walls covered with informative storyboards giving the background of local chiefs, the early history of the area, and the Voortrekker leaders and their journey from the Cape.

Family memories

Walking through the houses, one gets a feel for the married couple’s life: in the Georgian house, Kruger’s large Bible, and what is believed to be his pump organ. There are portraits of him and Gezina on the walls of the dining room.

There is little sense of Kruger except for a small fenced square at the back of the big house. Inside it is an arrangement of rocks in the form of a seat where he used to go daily to read and pray.

The Bible was the only book he read and it lay open next to his bed when he passed away in Clarens, Switzerland, in 1904 at the age of 78. The view from his room, overlooking Lake Geneva and the Alps, was a far cry from the warm blue skies of the Transvaal.

Kruger was buried in The Hague but his body was returned to Pretoria and buried alongside Gezina, who died in 1901.

On her death, he recorded in his memoirs, published in 1902:

“Shortly after my return to Hilversum, I received the heaviest blow of my life. A cablegram informed me that my wife was dead. In my profound sorrow I was consoled by the thought that the separation was only temporary and could not last long; and my faith gave me the strength to write a letter of encouraging consolation to my daughter, Mrs Malan.”

The Great Trek had started out with noble aims, guided by the Bible. Land was bartered in exchange for oxen and cows with the local chiefs.

“But God’s Word constituted the highest law and rule of conduct. The resolutions which came into general force contained, for example, the decree that it was unlawful to take away from the natives, by force, land or any other of their property, and that no slavery would be permitted,” wrote Kruger.

In time, cattle raids and battles with the Zulu Chief Mzilikazi and local groups changed the picture, and land was taken once Mzilikazi had been driven into present-day Zimbabwe. Kruger eventually owned 27 farms, and the Kruger family owned Boekenhoutfontein until 1971.

The land from which the local Bafokeng people were dispossessed would have been teeming with game. Kruger, like all the Boers, was an expert shot.

“It is, of course, impossible that I should be able to tell today how many wild beasts I have killed. It is too many to remember the exact number of lions, buffaloes, rhinoceroses, giraffes and other big game; and besides, it is nearly 50 years since I was present at a big hunt.”

He shot his first lion in 1839, at the age of 14. “As far as I know, I must have shot at least 30 to 40 elephants and five hippopotamuses. And I know that I killed five lions by myself.”

Leaving the republic

Elected president of the then Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek four times, Kruger boarded a train when the British were on their way to take Pretoria in June 1900. He headed east to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) and went to Europe by ship, never to return.

What must Kruger have felt sitting in Europe hearing snippets of news of the war and not having a role in the conflict? He heard of Lord Methuen’s defeat to General Koos de la Rey in March 1902. Reading in the news that Methuen was to be taken prisoner, he responded:

“I could not approve of that, and I hope that De la Rey will release him without delay; for we Boers must behave as Christians to the end, however uncivilised the way in which the English treat us may be.”

When the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed in May 1902, Kruger could have come home but refused; he didn’t want to live under British rule. He remained in Switzerland until his death. His body was brought back and railed up to Pretoria to be buried in the Church Street Cemetery.

I wonder if he would have preferred to be buried in rural Boekenhoutfontein instead.