When Andrew Canter of Futuregrowth Asset Management expressed doubts about more loans to Eskom and five other state-owned companies (SOCs), Eskom replied that it would “go elsewhere” for its “funding plan of R327 billion”. Eskom bonds would continue to be attractive as long as “its debts [are] guaranteed by government”.

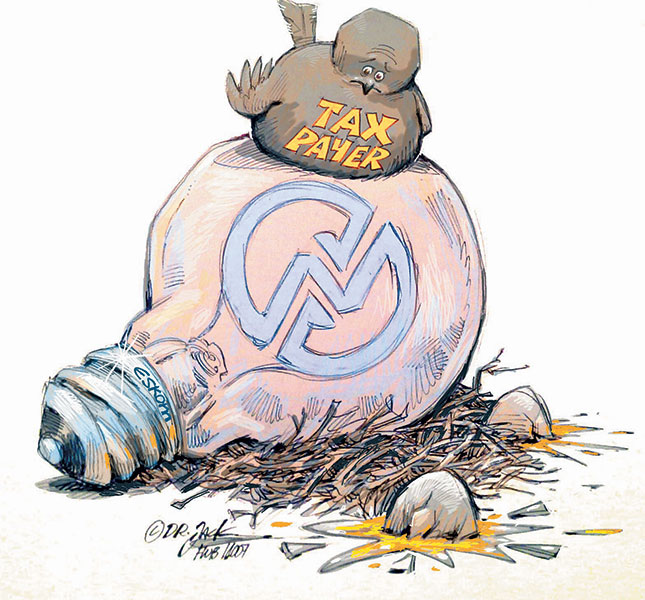

Such complacency is part of the problem that Eskom, South African Airways (SAA), Transnet and other SOCs present for South Africa. Even before Futuregrowth’s statement, the National Treasury had warned that existing guarantees, amounting to 11,5% of GDP, were a “source of pressure” on the country’s credit rating, which is due for reassessment before the end of the year.

Complacency is partly born of the sense of entitlement that pervades Eskom and other SOCs: they expect government to stand surety, as it has recently done again for SAA. Eskom also expects that the National Electricity Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) will readily pass on costs to consumers, among them farmers.

READ Cut electricity costs with wood gasification

According to a recent report by the parliamentary budget office, average electricity tariffs went up in real terms by 170% between 2007 and 2015. The retiring head of electricity regulation at Nersa, Thembani Bukula, said that if Eskom improved efficiencies, tightened up cost controls and carried out proper maintenance, it would not need large tariff increases.

These increases are not only reflected on consumers’ electricity accounts, they affect the operating costs of businesses, which then pass them on to the public, helping to keep South Africa’s inflation rate at the upper end of the target range (6%), and two or three times that of our major trading partners.

Efficiencies at Eskom have nonetheless improved, and President Jacob Zuma says there will be no more power outages. But there are many risks on the horizon. One is the Department of Energy’s proposal to give its minister, Tina Joemat-Pettersson, the power to overrule Nersa decisions (presently exercised by the courts).

Another is the huge cost of installing the additional 9,5 gigawatts of nuclear power that Zuma, Eskom CEO Brian Molefe, and some of their business associates favour. A third is the uncertainty about Eskom’s aversion to additional purchase agreements with independent power producers (IPPs).

A fourth is that Eskom will continue to apply racial and/or political criteria to procure coal and other supplies, unnecessarily pushing up costs. A fifth is continued violation of legislation on procurement and the management of public finances.

During the global financial crisis that began in 2008, governments in various other countries bailed out banks on the grounds that they were “too big to fail”. South Africa escaped the banking crisis, but Eskom in its present form has become “too big to save”.

Split Eskom in two

The solution is to unbundle, privatise, and introduce far more competition. This may sound radical, but it is not new in principle, as plans to split Eskom into separate generation and transmission companies were on the agenda soon after the ANC came to power in 1994.

This was part of what turned out to be a half-baked strategy of inviting greater private sector participation in a liberalised electricity market. Legislation was even drawn up to establish an independent grid operator for the transmission of electricity.

In its present form, Eskom is in a structured conflict of interest. It generates electricity, but is also compelled by the Department of Energy to buy it from IPPs at, what Eskom claims, are higher prices than electricity generated by its own power stations. The solution is simple: remove the conflict of interest by splitting generation from transmission.

Eskom’s two dozen existing power stations should be housed in separate companies and then sold to the private sector.

To avoid monopoly risks, limitations could be placed on how many each bidder could buy, and both local and foreign companies should be encouraged to bid.

The grid operator would own, run and maintain the grid. It would buy and sell electricity but not generate it, buying from the new owners of existing power stations, competing on price. Secondly, the grid operator would buy from companies installing new capacity, whether coal, wind, solar, water, gas, diesel or nuclear.

Installing new capacity would be entirely at the risk of these companies finding funding on capital markets. The cost of overruns would be for their own account and they would compete for contracts with the operator.

Companies relying on wind or solar power would have to make their own backup arrangements, although this problem would diminish over time as technology for storing energy improved and high storage prices dropped.

Alternatively, the grid operator could diversify sources widely enough to get the appropriate and most reliable mix of intermittent and base-load electricity.

The grid operator would negotiate price with suppliers, and the role of the department would fall away. As the operator would be the sole major supplier to businesses and households, prices would be subject to Nersa regulation, whose independence would be strengthened and its membership chosen in a public process similar to that used by the Judicial Service Commission.

However, anyone wishing to generate or purchase energy from outside the grid would be free to do so. They would also be eligible to sell any excess to the grid. No type of energy would receive any state subsidies, nor would the state seek to guarantee these markets.

What would become of Eskom?

Eskom’s survival in its present form is impossible without continuing subsidies extracted from consumers and taxpayers, including the enormous additional costs incurred by its notorious overruns. Higher and higher electricity prices will further damage the economy, while also driving more and more consumers off the grid.

It is possible that Eskom could disappear altogether, or become one of a number of competitive suppliers, or it could reincarnate itself as the grid operator, which would itself be privatised. Among the present Eskom-owned facilities that could be sold would be Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations.

They are well over the deadline for completion and far over budget, and could be sold at bargain basement prices to whoever would be willing to shoulder their debt and remaining completion costs – estimated at anything up to R300 billion. The objective would not be to profit from their sale, but to get them off the public balance sheet.

As for more nuclear power, capital costs have been estimated at between R650 billion and double that figure – far beyond government’s financing ability or guarantee. Anyone wanting to put up that kind of money would be free to build nuclear power stations at their own risk.

They would negotiate with the grid operator to supply nuclear-generated electricity at an agreed price when it became available.

Apart from reducing the risks to the country’s fiscal position, the breaking up and privatisation of Eskom would subject the entire electricity-generation function to the disciplines of the market.

It is more difficult to buck these than it is to shrug off procurement procedures or other demands by Treasury, especially when the latter cannot be sure of Zuma’s backing in disputes over accountability or governance.

The sale of Eskom’s power stations would have to be an entirely transparent process, managed not by the Department of Energy, or even Treasury, but independent agencies such as consortia of local and foreign investment banks.

This would help guard against one of the problems that has accompanied privatisation in countries such as Russia, where the old SOCs were captured by the so-called ‘oligarchs’. This would be a major risk to South Africa.

Privatisation would also solve the inefficiencies arising from overstaffing, which is so characteristic of SOCs.

Privatisation in the UK under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s led to substantial job losses, but it helped pave the way for today’s far more efficient and job-creating British economy. Millions of workers were also laid off in China as that country began economic liberalisation 40 years ago.

Job losses are inevitable because companies accountable to shareholders in competitive markets cannot afford overstaffing. Both to compensate those affected, and reduce resistance to privatisation, Eskom’s power stations employees would need to be offered share options.

At the same time, South Africa’s overregulated labour market would have to be liberalised to reduce the risks of hiring additional employees, and generous state subsidies would be needed to retrain retrenched workers.