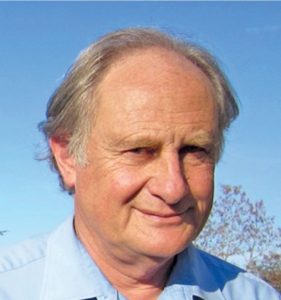

From where does your interest in the Karoo and idea for the book stem?

Although my career as a historian has been in the UK, I was brought up in Cape Town in the 1950s and 1960s.

As a child I travelled through the Karoo every year, by train to Pretoria. The landscape was foreboding but its starkness was appealing.

READ Community involvement in conservation and tourism

My research interest in the environmental history of the Karoo came by an unusual route. Trying to understand more about the history and experience of African people was a central project.

I did my doctoral research in Mpondoland in 1976-7 when the government policy of betterment or rehabilitation was still an important issue. Government planned to move rural African people from their scattered settlements into villages to demarcate selected areas for agriculture and to fence the vacated pasture lands.

Interventions

The plan was to cull cattle through enforced sales. These were the major interventions in African rural life. The motivation for this largely unpopular policy was officials believed that the Bantustans were overstocked, causing soil erosion that would destroy agriculture.

They were determined to introduce a system of rotational grazing and to end the kraaling of livestock. For this they had to clear the scattered settlements, empty out the communal grazing lands and fence them into camps.

The origins of these ideas led me to the Karoo, a different world of large, privately-owned farms, of drought, sheep and jackals.

The Drought Commission of 1923, chaired by HSD du Toit, a South African War hero and senior agricultural official, inquired into environmental degradation and soil erosion, which it saw as a national disaster, especially in the Karoo.

This report blamed overstocking by sheep and goats. And they blamed not least the predation of jackals which forced the nightly kraaling of sheep and a daily trek to pasture that ‘hammered’ the veld.

READ Tackling climate change and biodiversity loss

Their solution was to eradicate predators like the jackal, and introduce rotational grazing in fenced camps. I found these semi-arid districts were not backwaters but dynamic sites of economic development and of social and environmental thinking in South Africa.

I became fascinated by the environmental ideas and debates that were generated by the intensification of the livestock economy since the introduction of merino sheep in the 19th century.

It became clear measures being imposed unthinkingly in the African settlement areas derived from the large farms of the Karoo.

I pored over old government reports and articles in agricultural journals, including inquiries into the jackal and prickly pear, and then took to the road, visited farmers, found old diaries, and walked through the veld in the hopeless task of trying to understand the changing vegetation.

My distant memories of the Karoo, its space, its stillness, the mountains rearing up from the veld, were renewed.

The book was the outcome. Chapters cover issues that were part of everyday conversation on Karoo farms – drought and water, dams and boreholes, dongas and invasive plants, jackals and dassies and a preoccupation with sheep and goats, ostriches, fences and fodder.

What have been the biggest changes in the Karoo in your lifetime?

Two big changes since I was born (1951) have been the relative decline of the importance of wool; and the stabilisation, even improvement, in the Karoo environment.

In the early 1950s, wool was the golden fleece, and next to gold, by far the most valuable export. But by the 1950s, there was widespread consensus that environmental conditions had deteriorated.

Serious drought in the 1960s worsened the problems; there was an environmental low point from the 1920s to the 1960s.

Signs of recovery

However, there are increasing signs of recovery. Probably the major factor in this stabilisation, even improvement, is the decline in livestock numbers.

What also helped was the stock-reduction scheme implemented in the Karoo from the late 1960s in which farmers were compensated for destocking, and there were subsidies for water provision and fencing.

Larger farms, assistance with farm planning, and increased environmental consciousness all played a part. Cultivation of vleis for wheat and fodder, a cause of gulleys, largely stopped.

Systems of internal fencing and rotational grazing were implemented across the Karoo and boreholes provided dispersed water supplies.

My interviews in the 1990s with farm families around Graaff-Reinet and the eastern Karoo, suggested that commitment to conservationist ideas and strategies was widespread.

In the former Ciskei, on the eastern edges of the Karoo, environmental conditions have also improved, because many families have abandoned cultivation; burning of pastures is less common and livestock densities are lower.

There has been an expansion of national and provincial parks as well as private conservancies.

Wildlife farming has become a major new enterprise. Predators and baboons are thriving again and are probably an additional factor, together with theft, in reducing livestock numbers.

Wildlife farming also encourages restoration of indigenous habitats. But it is not all good news.

Climate change is probably leading to a decline in rainfall in the western Karoo and to more intense storm rainfall in the eastern parts, which could intensify gulleys. While prickly pear is controlled, invasive plants such as prosopis and jointed cactus remain a danger.

How will the Karoo’s future unfold?

Now that there is some environmental stability, the greatest problem is inequality. Black people were prevented from owning land.

Press, Cape Town. Visit oxford.co.za.

Karoo towns were fully segregated by race. At the same time, some small towns decayed as their role in servicing the farming economy was bypassed while small farms dwindled and poverty became widespread.

Clearly, land reform will need strong support from the private sector, non-governmental organisations and the state if it is to improve livelihoods. One example is the National Woolgrowers scheme for communal farmers.

It has been suggested that the Karoo be turned into a huge open range commonage for wildlife and that this would be the most ecologically benign solution. I don’t think that this would be the best way forward.

First, although the idea of rewilding is popular in some circles, we must accept that all natural environments and wildlife need to be managed if they are to survive.

Control is essential and this is probably best achieved through a mix of state-owned protected areas and private property.

Second, the Karoo in the past was able to generate substantial livelihoods and that may still be possible if investment is encouraged.

Third, the land still has considerable value and people live there. It would be too expensive to buy them all out.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) astronomy project in the Western Karoo probably constitutes the largest recent investment in the region.

Like most megaprojects it has both negative and positive impacts. More thought needs to be given as to how SKA can tie in with local needs.

There is scope to make parts of the Karoo a hub of green power. Major investment will, however, be needed in the infrastructure not only for generation but for storage and transmission.

Can tourism play a real role in the economy?

Tourism has been promoted in the Karoo for some years and has contributed to renewal in some small towns. While national parks and wildlife farms are leading to a decline in farm employment, they have been a factor in the growth of Karoo tourism.

Perhaps this will generate alternative jobs. More generally, tourism has strong environmental, outdoor and historical reference points.

Symbols such as old houses, windmills, old farming implements and especially traditional food, abound in the marketing of Karoo tourism.

Local alcohol such as iqhilika/karee, prickly pear beer and local distilling could be revived.

Large farms with handsome Victorian farm-houses have been opened out for accommodation; the farmlands are increasingly porous for those with mobility and money.

Travel magazines have been successful in making the cultural and environmental links. Ecotourism is popular and people are prepared to learn about animals and vegetation.

More could be made of rock art and pre-colonial legacies, as has been done at the !Khwa TTU San museum near Cape Town. Landscape, space and stillness have their own attractions.

As the COVID-19 years reminded us, tourism is fragile, and some see it as catering largely to an elite, further skewing social division. But it can help create broaden infrastructures of participation and connectivity.

For many it seems a quiet, untouched place. Yet it has a surprisingly dynamic history, with new people, new animals, new patterns of ownership, wealth and agricultural techniques.

It is unlikely the agrarian economy will provide the dynamism for growth, but the coupling of environmental and energy economies offer promise. A new economic dynamism does not have to result in eco-degradation.

Email Prof Willam Beinhart at [email protected].