Sustainably feeding an expanding global population depends on how well we protect our food systems from threats. This is especially true when it comes to managing antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is rapidly becoming one of the greatest perils to lives, livelihoods and economies.

Combating the pace of resistance

AMR is a process whereby micro-organisms acquire a tolerance to antibiotics, fungicides and other antimicrobials, many of which we rely on to treat diseases in people, terrestrial and aquatic animals, and plants.

One of the consequences of antimicrobial-resistant micro-organisms is drug-resistant infections. Resistance is already making some diseases in humans, livestock and plants increasingly difficult or impossible to treat. It is undermining modern medicine, compromising animal production, and destabilising food security.

The impact of AMR is further amplified by the slow and expensive process of developing replacement medicines. Current research and development of new antimicrobials and health technologies to address AMR is inadequate and in need of incentives and investment. For these reasons, AMR affects everyone and requires all of us to take urgent action.

We need to keep antimicrobials working for as long as possible to buy time for the discovery of new drugs. Together, we must combat the accelerating pace of resistance and make food systems more resilient.

Protecting food and health systems is a common need of our global society. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) shares a responsibility to guard against economic losses as resistant microbes contaminate environments, cross borders and spread readily between people and animals. The time for action is now.

Practical and preventive adjustments

The world is expected to produce the same amount of food over the next 30 years as it has produced in the past 10 000 years. This places unprecedented pressure on our agriculture systems to deliver nutritious food safely and sustainably in the face of climate change, diminishing natural resources and global health threats, which include pandemics and drug-resistant infections.

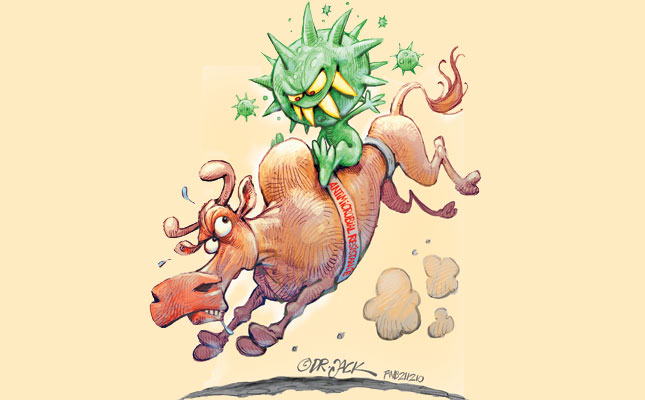

Within the next 10 years, antimicrobial use (AMU) for livestock alone is projected to nearly double to keep pace with the demands of the growing human population. Usage for aquaculture and plants is predicted to continue rising as well. The intensification and specialisation of agricultural production is already contributing to infections.

Human and animal waste, wastewater from hospitals and clinics, and discharge from pharmaceutical manufacturing sites contaminated with resistant microbes and antimicrobials can also enter the environment. These factors will speed up the emergence and spread of resistance unless we act now to improve practices to minimise and contain AMR.

Many improvements in agriculture practices to control AMR more effectively, such as good nutrition, health, vaccination, hygiene, sanitation, genetics, husbandry, welfare, environmental protection and growing methods, help boost production in addition to protecting against losses from infectious disease. This can make agriculture more profitable and more sustainable.

In fact, there is a strong economic benefit to seizing this window of opportunity for implementing practical and preventive adjustments at relatively low cost now, compared with the 1% to 5% or greater loss of GDP predicted for countries if AMR remains unchecked.

Web of transmission

In support of inclusive protection, the FAO champions multisectoral and multidisciplinary responses coordinated through strong governance, informed by surveillance and research and which promote good production practices and responsible AMU.

The expansion of communication and behaviour change initiatives are also urgently needed to target the drivers of AMR and empower stakeholders to improve their practices. Since the advent of antimicrobials, the occurrence of resistant micro-organisms in livestock has grown exponentially.

The widespread presence of antimicrobial-resistant micro-organisms in terrestrial and aquatic animals, plants and the environment is influenced by an interplay of factors across sectors.

These include:

- Anthropological, behavioural, sociocultural, political and economic factors;

Poor sanitation and limited access to clean water; - Limited biosecurity and production practices that lead to an overuse of antimicrobials;

Absent or inadequate oversight of AMU in agriculture, with limited access to animal and plant health experts, as well as inadequate training of, and support for, these experts; and - Unregulated sales of antimicrobials without prescription, and increased availability of counterfeit and low-quality antimicrobials, including products with harmful combinations and subtherapeutic concentrations.

The intermingled web of transmission pathways of antimicrobial-resistant micro-organisms includes the potential for emergence and spread across all sectors and stages of the food supply chain. Timely action can help limit the spread of food-borne and zoonotic antimicrobial-resistant micro-organisms that may reach humans, animals and crops through a multitude of transmission pathways.

These include both direct contact with animals and human sources, and indirect transmission through the environment and food supply chain.

AMR can originate at the point of production and be carried by animals and plants into the food chain. Resistant micro-organisms can also be introduced during the handling, processing, transport, storage and preparation of food products. Once people become carriers of antimicrobial-resistant micro-organisms, they can easily spread AMR within and between communities.

AMR can also reach the general population by spilling over from human and agricultural sources into the environment and wildlife populations, and people can then be exposed through contaminated water, soil and agricultural products.

The way forward

Contributing towards the goal of building resilience in the food and agriculture sectors by limiting the emergence and spread of AMR depends on controlling AMR effectively as a shared responsibility among farmers, herders, growers, fishers, prescribers and policymakers in food and agriculture, as well as other sectors.

AMR threatens progress in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals as more agriculture producers may struggle to prevent and manage infections that threaten to disrupt food supply chains and thrust tens of millions more people into extreme poverty (World Bank Group, 2017).

To respond to this challenge, the FAO has established two main goals for its work on

AMR. The first is to reduce AMR prevalence and slow the emergence and spread of resistance across the food chain and all food and agriculture sectors, and the second is to preserve the ability to treat infections with effective and safe antimicrobials to sustain food and agriculture production.

The FAO Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance suggests five key objectives to help focus efforts and accelerate progress in the fight against AMR: increasing stakeholder awareness and engagement; strengthening surveillance and research; enabling good agricultural practices; promoting responsible use of antimicrobials; and strengthening governance and allocating resources sustainably.

Success in containing AMR, keeping antimicrobials working, and boosting the resilience of food systems will depend on targeted and sustained efforts in all five areas, which are mutually reinforcing.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

This article is an edited excerpt from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ report titled ‘The FAO Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2021–2025’, which was published in 2021.