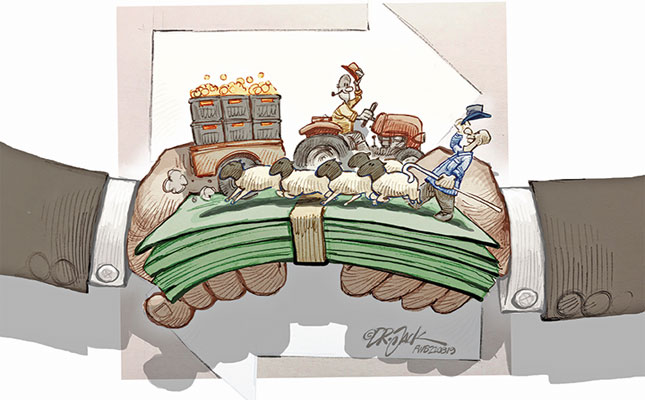

The expansion of trade in food and agriculture since the beginning of the 21st century has strengthened the interdependence of agrifood systems across the world.

New players have emerged as important exporters in the global market while several countries depend on imports from other regions. More food and agricultural products cross borders and trade is facilitated by multilateral and regional agreements.

The globalisation of food has provoked lively debates on what outcomes global markets generate and has raised significant concerns about the impact of trade on the environment, society, changing lifestyles and diets.

Opponents to globalisation maintain that trade is harmful to sustainable development. Switching to locally produced food and reducing trade are seen by many as providing better environmental and social outcomes.

Nevertheless, trade in food and agriculture has been an essential part of our societies, and discussions about the globalisation of food often overlook the fundamental drivers that shape global food and agricultural markets.

Why do countries trade?

Nowadays, technology differences across countries still drive international trade in food and agricultural products. Technology underpins a country’s absolute advantage in trade; it determines how the factors of production, such as land and labour, are combined, making them more productive and reducing costs.

In food and agriculture, technology includes anything that can influence the transformation of production factors into outputs. Improved seeds, fertilisers and machinery, digital technologies, innovations in organisation and farm management practices, and improvements in education and extension make up agricultural technology and shape absolute advantage.

Countries engage in trade to export what they can produce at a lower cost relative to other countries, while importing what is relatively more expensive to be produced domestically.

While a country’s absolute advantage is determined by its productivity level, comparative advantage reflects the opportunity costs of production and entails a comparison both across countries and across products.

With food and agricultural trade increasing twofold in real value terms since 1995, and with more countries participating more actively in global markets and more trade flows among them, the principle of comparative advantage is increasingly relevant in the modern economy.

Allocation of natural resources

Together with technology differences, the uneven allocation of natural resource endowments across countries forms another key determinant of comparative advantage in food and agricultural trade.

Land and water are crucial factors in food production, and their availability can influence the relative cost of agricultural products and shape comparative advantage. For example, water-stressed countries rely on imports of water-intensive foods to complement domestic production and ensure food security.

Countries with abundant land or water can export food and agricultural products that use these factors more intensively and capture large shares of global trade.

Given the available technologies and resource endowments, countries specialise in agricultural products in which they are relatively more productive. And by engaging in trade, countries can gain by exporting these products for which they possess a comparative advantage, while importing products in which they have a comparative disadvantage.

This does not mean that countries should only produce and export the products for which they enjoy a high comparative advantage, but that they tend to produce and export relatively more of these products, as markets provide incentives to specialise in the form of price differentials.

The gains from food and agricultural trade can be significant. Differences in technologies and the natural resources necessary for agricultural production, such as land and water, are substantial across countries. For example, agricultural land per capita in the US is about 25 times higher than in Japan.

Recent studies looking at how market integration helps allocate agricultural production according to comparative advantage suggest that gains from trade can be significant.

Without trade, such large differences would result in very high food prices in countries with few natural resources per capita and very low prices in countries with larger endowments of land and water. This would also have significant implications for food security.

Who benefits?

Gains from food and agricultural trade are not distributed evenly. Trade affects the prices of foods and production factors, including labour, and can result in winners and losers. In agriculture, a major concern relates to the ability of smallholder farmers in developing countries to compete effectively in global markets.

For these farmers, market failures, such as poorly functioning land and labour markets and limited access to technologies, credit and insurance can erode any comparative advantage and dissipate the gains from trade.

Analysing comparative advantage, the key determinant of food and agricultural trade, in a world of many countries and many products is difficult and it may not be possible to measure it precisely. Traditionally, practitioners measure the export performance of a country in a particular product relative to the global market to reveal comparative advantage.

Since a country with a comparative advantage can produce goods relatively cheaper than its trade partners, high comparative advantage relative to the rest of the world would be associated with exports, and low comparative advantage would be associated with imports.

However, using observed data in this way does not adequately reflect the fundamental comparative advantage. This is because agricultural and trade policies distort markets, and relative prices and the observed trade patterns of a country are determined on the basis of these distorted prices, rather than by underlying relative productivity levels and the availability of resources.

Developments in quantitative trade models provide a better connection between the theory and the data and, although they do not measure comparative advantage for each country, they explore its role in shaping trade flows between countries.

In these modelling frameworks, the influence of comparative advantage is assessed by the heterogeneity of relative productivities across trade partners, which, in turn, can generate price differentials and thus provide incentives for trade.

For example, the higher the heterogeneity of relative productivity across countries in the global market, the stronger the influence of comparative advantage. Agricultural and trade policies, such as subsidies and border measures, can weaken the underlying role of comparative advantage in determining trade flows.

They could even reverse the relationship between comparative advantage and trade, causing particular goods that would have otherwise been imported to be exported, and vice versa.

For example, this could happen with policy measures such as export subsidies, which have been eliminated for agricultural products by the 10th World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference held in Nairobi in 2015.

Other policies, such as non-tariff measures (NTMs), including sanitary and phytosanitary standards, could also affect the impact of comparative advantage on trade flows. Although many NTMs aim to improve the safety and quality of food, address environmental and health issues, or support social norms, they can increase costs related to trade as exporters have to comply with different standards in order to export to different destination markets.

The increasing prevalence of NTMs in food and agriculture means increasing costs for trade but, at the same time, weaker regulations could result in negative environmental, health or social outcomes.

Trade costs, in general, strongly affect trade flows. Transport costs are significant, increase with distance and influence food and agricultural trade between countries. Other costs include search and communication costs, or costs associated with documentation, procedures and clearance delays at the border.

Trade costs are likely to be higher for agricultural products and perishable foods, such as fruit and vegetables.

They are also significantly higher in developing countries where transport and communication infrastructure are relatively poor, thus limiting the opportunities for trade that would potentially arise due to comparative advantage.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

This is an edited excerpt of a Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations report titled ‘The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2022’.

.