Photo: FW Archive

Could a recently retrenched individual who has always dreamt of farming take R1 million from his or her pension savings and start a farming operation in South Africa’s current economic climate? The answer is yes, no, and maybe.

In this case, the devil truly lies in the detail. For this hypothetical farm, Farmer’s Weekly limited the scope to pig, poultry (both layers and broilers), vegetables and lucerne. While experts quickly dismissed some of these hypothetical farms, others just might be possible.

READ How two brothers built a R100-million farming business in 10 years

A few assumptions are necessary. The first is that the farm is in Gauteng, close to a market. The second is that the potential farmer does not own land and has no political means of obtaining land.

According to Michael Corbett, FNB’s head of agriculture in Gauteng, leasing land would probably be the best bet. After all, there is a difference between being a farmer and being a landowner.

“A quick Internet search indicates that we could possibly find land to lease for between R10 000 and R12 000 a month. Depending on size and infrastructure, this could work for a new farmer.”

Agricultural economist and independent consultant Jan de Jong agrees with Corbett.

“Leasing does make sense, because you’ll be able to free up capital. Unfortunately, it does have the downside of not having security. That’s a risk that the farmer would have to manage.”

Johann Kotzé, agricultural economist and CEO of the South African Pork Producers’ Organisation, says that when leasing land it is important to keep infrastructure to a bare minimum, as it will not necessarily benefit one’s farming operation to build infrastructure on another person’s land.

De Jong stresses that the potential farmer has to understand the crucial importance of profit.

“You are not a developing farmer; you are a small commercial farmer. When looking at these hypothetical farms, keep profit in mind. This should always be your motive. Even if you decide to exchange your cabbages for eggs, or vice versa, a transaction is still taking place.”

No-go options: Pigs and lucerne

The cost of the infrastructure needed to start a commercially viable piggery makes this option unfeasible for a R1 million start-up.

“To get the housing up and running for a single sow will cost around R85 000. It’s incredibly expensive to start a piggery,” says De Jong.

READ The influence of weather on lucerne hay quality

Corbett concurs, saying that in addition to costly infrastructure, good genetics are crucial.

Kotzé also believes that a piggery will not work in this particular scenario, but cites the high biosecurity risk as the main problem.

However, if a beginner farmer decides that money is no object after all, and wants to start a piggery, it is important to keep an eye on feed prices, as feed amounts to 70% of pig farming costs, says De Jong.

“Moreover, 50% of that is linked to the maize price, which is extremely high at the moment.”

Another option that is less than ideal is a lucerne farm, according to De Jong, who adds that it is important to look at the value per kilogram.

“Lucerne needs a lot of water, you need heavy equipment and your potential market is quite small. You’ll only be able to sell to other farmers.”

Maybes: Vegetables and broilers

Our experts are divided when it comes to broilers. De Jong says that it might be a viable industry, as a farmer does not have to spend too much on infrastructure.

“There are many farmers who have carved out a niche for themselves,” he says, adding that a producer could raise broilers in a free-range set-up and sell them live.

“The venues where people collect their social security grants could be great locations to sell live chickens. It makes sense for a person without a fridge to buy a live chicken and slaughter it at home. The same cannot be said for pigs.”

Corbett, however, says that the figures do not support the idea of farming broilers on a small scale.

De Jong believes that vegetables are the easiest to get to market, but the type of vegetable is a crucial factor. Cabbages or butternuts, for example, could be profitable.

“What’s good about these is that you’ll be able to store them,” he adds.

De Jong believes that farmers should consider growing vegetables that are not readily available. “Don’t try to compete with mega-farmers by producing tomatoes.”

Farmers should rather consider crops such as marog (wild spinach), rocket or edible flowers.

When researching the feasibility of a vegetable farm, De Jong suggests starting at the end of the value chain and working backwards.

“First, find your market. Only then will you be able to work your way back to what, where and when you’ll be able to produce. If you don’t do this, you’ll end up being a price-taker.”

Would-be farmers should also consider adding value to their products, says De Jong. An example of this would be vegetable preserves.

Corbett says that a cash crop such as lettuce could also be a viable option for new entrants. It costs at least R3,29 to produce a head of lettuce, and with hydroponics this goes up to R6,29. The average retail price of lettuce is around R10,40/ kg.

“This comes down to a profit margin of around 40c per head of lettuce,” says Corbett. “The margins would be tight, but this could potentially be an option to consider.”

The probable winner: Layer hens

Corbett says that after discussing the matter with farmers and other industry insiders and looking at financial feasibility, it seems the safest option is to start a layer farm for R1 million.

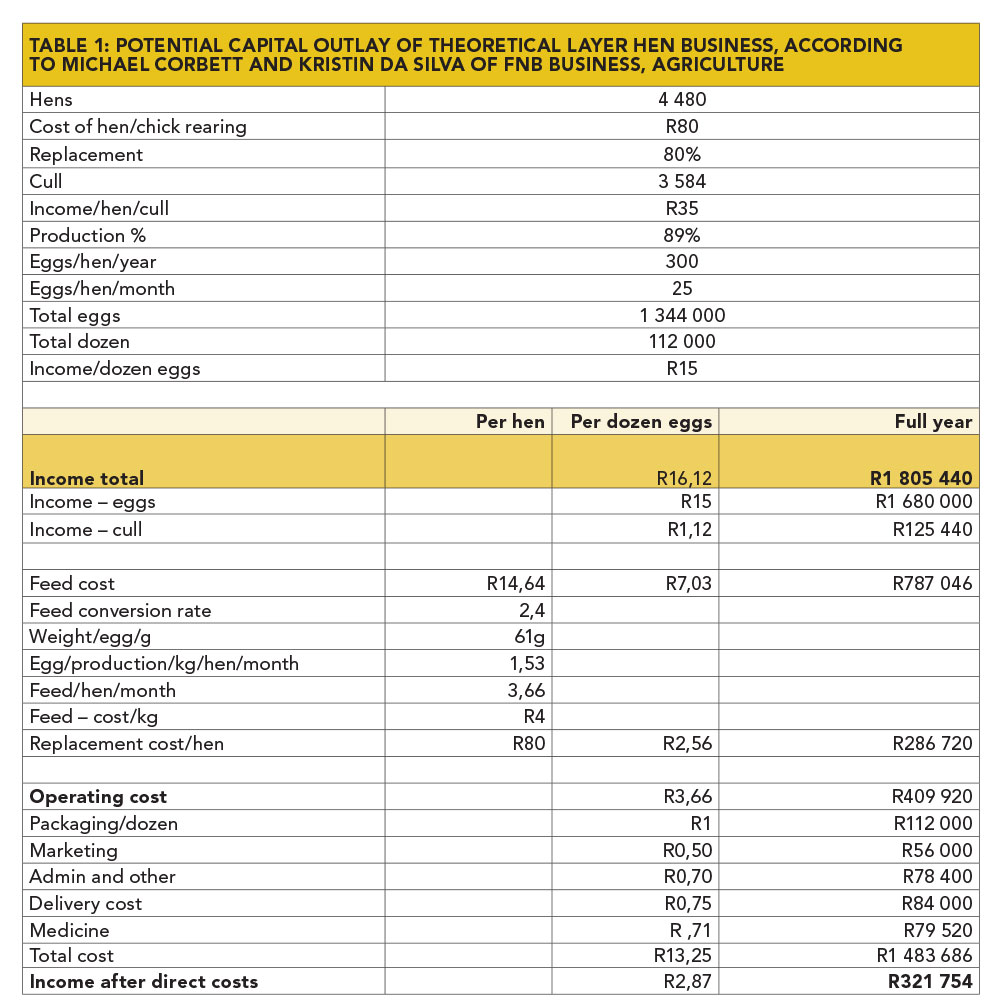

This assumption is based on a 4,9ha piece of land near Benoni advertised on safarmtraders.co.za. The property has a storeroom of 800m2 that should be able to house two layer cages. A basic cage can be procured for R110 000, so this would be an infrastructural investment of R220 000. The cages are large enough to house 4 480 chickens (See table below).

“A good farmer can get 330 eggs/ chicken/ year, but for our theoretical farmer I’ve worked

on a figure of 300 eggs.”

This amounts to 1 344 000 eggs (112 000 dozen) annually. At an assumed selling price of R15/dozen, the income from egg sales would be R1 680 000.

“We’re also working on the assumption that every hen, which costs around R80 to procure, could be culled and the farmer would be able to receive R35/hen,” says Corbett. He adds that if the replacements were estimated at around 80%, then 3 584 culled chickens would add R125 440 to the farmer’s bottom line.

This means that a farmer could potentially earn R1 805 440 per annum. “But this is only your income. Costs still need to be deducted to determine profit,” he points out.

The estimated feed costs for running such a layer farm would be R787 046 and hen replacement costs would escalate to R286 720 per year, according to Corbett’s calculations.

Other variable operating costs that must be considered are packaging (R112 000), marketing (R56 000), administration (R78 400), delivery (R84 000) and medicine (R79 520). Corbett’s estimate shows that total annual costs could amount to R1 483 686. A farmer should also ascertain whether he or she needs to have an environmental impact assessment performed on the property.

Water, electricity and rent were not included in the calculation. However, it seems as if a farmer could expect an annual profit of just over R320 000 after deduction of costs. If the cost of utilities were added at R12 000/month, profit would be reduced to R176 000/year (R14 999/month).

A farmer should also factor in losses that could be suffered. Corbett says it is probably more realistic that a farmer would earn around R10 000/month from this farm.

Phone Michael Corbett on 011 269 9777, or email him at [email protected]. Phone Jan de Jong on 082 783 9538, or Johann Kotzé on 012 100 3035.