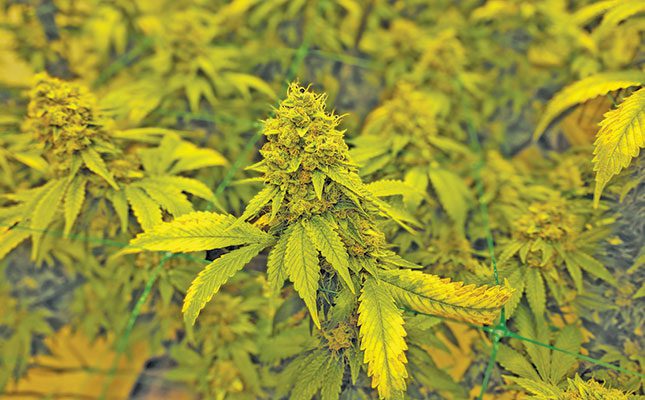

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The cannabis industry in South Africa is often touted as a potential saviour of the country’s ailing economy, and one look at the figures explain why.

There is R107 billion of value in the local industry waiting to be unlocked. In 2019, Prohibition Partners released its African Cannabis Report, which forecast the value of the South African medicinal cannabis market and that of the recreational cannabis market at R11 billion and R20 billion by 2023, respectively. The projected growth rate is 28,4%.

South Africa has the capacity to become a leader in this dynamic space. The country enjoys a strong head start on others, a good reputation internationally for quality of product, and is rated number one in Africa for technical competence and cost of production. In addition, its favourable climate, loosening laws, arable land and pre-existing experience in farming and hemp production make it a formidable force.

Despite all this, the industry remains in the very early stages of ironing out the various legal, political, economic, regulatory and social obstacles standing in the way of its potential.

Some advanced economies and sophisticated markets have not been shy to put their faith

in South Africa’s medicinal cannabis industry as cannabis use grows across the globe.

Germany, for example, has recently become the most developed market to allow the use of cannabis to treat medical conditions, with recreational cannabis (adult use) to be ratified within the next 12 months.

Investment drive

A number of European countries have relied on South African producers to source medical cannabis products. This may explain why the JSE-listed cannabis giant Labat Africa Limited was on a major investment drive that ended in late 2022. The group is also listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange (FSE) in Germany.

The company has made a number of notable investments in the past 18 months, including the acquisition of a 100% shareholding in Miami-based CBD lifestyle brand Echo Life. It also has the rights to distribute American pre-rolled hemp smokable Ace & Axle for 10 years locally.

In March 2022, Labat acquired Sweetwater Aquaponics (with its working capital requirements), a medicinal cannabis cultivation and processing facility in the Eastern Cape worth R11,5 million. The group is also funding its own biodata observational research into the replacement of opioids for pain management by medicinal cannabis.

Labat’s retail division, operationalised through CannAfrica, was also capitalised in the same period. It has invested more than R20 million of its own cash resources to build a medicinal cannabis value chain.

This will see its Labat Healthcare subsidiary fully integrated, with a deep focus on cannabis, and with cash investments continuing into its extraction capability since its latest collaboration with Californian partners.

According to Labat CEO Brian van Rooyen, South Africa needs to urgently address the constraints preventing the country from reaping the fruits of the local industry’s potential.

Since the Constitutional Court decriminalised cannabis for personal use in 2018, discussions on regulation have been ongoing. The Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill was drawn up and is still waiting on Parliament to be ratified. The Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development presented Parliament with a master plan in 2021 detailing how cannabis could be incorporated into the business sector.

And in last year’s State of the Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa said government was looking to streamline the cannabis regulation process, which could unlock 130 000 jobs.

Slow legal process

Van Rooyen says the right framework needs to be enabled as soon as possible so that growers can be involved in every part of the value chain.

“South African businesses can obtain licences to grow, cultivate and export cannabis. All levels of government are saying how much money can be made out of cannabis, but businesses won’t make that money if the legislation isn’t changed.”

The sluggish regulatory process is due to cannabis’s stigma as a narcotic tied to illicit trading.

“Development banks and potential financiers are reluctant to invest in cannabis because of its legacy reputation, and it’s not yet dealt with as a new economic category. They don’t have a clear picture of what the commodity can bring to the economy,” says Van Rooyen.

Labat Healthcare director for business development, Herschel Maasdorp, says changing legislation means amending several laws for best regulatory reform. Cannabis can be regulated through the Drugs Control Amendment Act or decriminalised through safety and security legislation, amongst others.

“All of these regulations where amendments can be issued on behalf of cannabis will inform the commodity’s commercial trajectory.”

Maasdorp says the absence of a sophisticated policy framework is an indictment of government agencies. “In South Africa, by now, we should have a recommended price per gram of different profiles of cannabis for different markets and purposes. And from the specific price point, each constituent in the value chain should get its share.”

He adds that the new auditing metrics for cannabis could potentially land the industry in the same dilemma as the wine industry, whereby high-quality products are underpriced for the international market. Labat currently sells to dispensaries in Brisbane, Australia, at a locally competitive price per gram, but these sell the prepacked, finished product at a margin as high as 600%.

Labat’s Healthcare division recently received an additional offtake order for a monthly supply of 200kg of product to Switzerland.

“South African companies shouldn’t allow the international market to dictate the price of our commodity,” says Maasdorp. “We’ll run the risk of becoming the backyard for the global pharmaceutical cannabis industry.

“If we can get the laws right, and market enablers and the regulations aligned, we can attract the ideal investors. When that happens, cannabis can begin to navigate its way out of the dark alleyways of illicit trade and into the formal economy as a legitimate economic category.”

Labat has been building its cannabis value chain over the years, from research and cultivation to manufacturing, distribution, retail and recently, consulting. Through its acquisitions, it has expanded to include genetics and extraction.

“Because we’ve developed a repository of intellectual property under a company called The Highly Creative Consulting, we’re now assisting African governments with their legislative framework at policy level,” says Maasdorp.

Labat became the first listed cannabis company on the JSE, with a dual listing on the FSE and 18 000 shareholders. Thanks to the FSE listing, it is setting up a direct marketing and distribution line into Europe. It plans to launch a pharmaceutical sales, marketing and distribution company in Germany in June this year.

South Africa simply needs to get serious about the cannabis industry. Fostering enabling legislation across the value chain should fuel the cannabis sector to new highs, and in doing so, boost the economy and assist with economic recovery. With the country already boasting plenty of sunlight and an abundance of land suitable for industrial hemp, it is an ideal location for productive cannabis crops.