Photo: UPS Battery Center

Alessandro Volta, an Italian chemist and physicist, discovered in 1799 that when two dissimilar conducting materials, or electrodes, are covered by a solution that can conduct electricity, an electrolyte, one material will become positively charged and the other negatively charged.

READ New from Desmond Equipment

If these terminals are connected by an external circuit, an electrical current will flow from one to the other. With this discovery, Volta had in fact invented the world’s first battery.

I apologise in advance for introducing some chemistry, but it is difficult to understand the operation of the modern battery without it. The concepts are not difficult to understand.

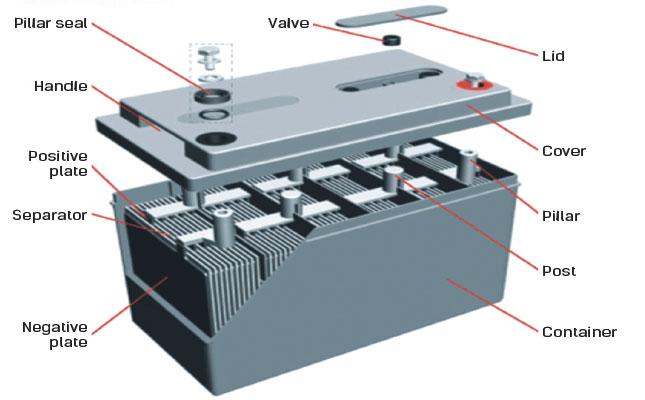

During battery manufacture, both the negative and positive plates are coated with a muddy mixture of lead oxide, sulphuric acid and water.

The plates are passed through a flash-drying oven and then cured for two days in a humid, temperature-controlled environment. This stabilises the plates chemically, and converts any free lead in the paste to lead oxide.

The plates are then assembled into a battery, which is usually shipped in a dry, unformatted state called a ‘green’ battery. The selling agent formats it by pouring in sulphuric acid to act as an electrolyte, and charging it for a period.

This causes the oxygen molecules to leave the negative plates and migrate to the positive plates.

The result is that the lead oxide (PbO) on the positive plates changes into dark chocolate brown lead dioxide (PbO2), and the lead oxide on the negative plates changes into grey sponge lead (Pb).

When a current is drawn from the battery, it starts to discharge, and some of the acid electrolyte combines with the material on both plates to form lead sulphate and water.

This results in a reduction in acid strength that can be measured by the change in specific gravity (SG) measured in kg/litre. The SG value is 1 270 for a fully charged battery, but drops down to 1 150 for a discharged battery.

(Pure water gives a reading of 1 000.) This can easily be measured with a hydrometer; a device fitted with a float whose depth in the fluid is a measure of the SG.

At a slow rate of discharge, the water formed at the plates has sufficient time to migrate away from the plates to allow enough acid to remain in contact with the plate material so that normal discharge can continue.

When the discharge is fast, the presence of water prevents acid from reaching the plates, with the result that the battery voltage falls away rapidly. After a rest period to allow the water to move away from the plates, such a battery will revive.

Back to square one

When the battery is recharged, the above actions are reversed. The acid is released from the plates, but drops to the bottom of the cell. It is denser than the weakened electrolyte and does not mix easily with the rest.

READ Managing no-till soil acidity and fertiliser requirements

The positive plates slowly revert to carrying lead oxide and the negative plates once again become covered with sponge lead.

At the start of the charging process, the cell voltage is about 2,1V and this increases steadily.

By the time it reaches 2,35V, gassing will begin. This occurs when the current passing through the cells is not fully utilised to convert the plate materials.

The excess current breaks the water down into hydrogen and oxygen, a process known as electrolysis.

The gas bubbles formed stir up the denser layer of acid at the bottom of the battery. This restores the SG to the correct value and causes the voltage to level off at about 2,7V, which indicates a fully charged battery.

If the charging rate is too high, gassing will set in prematurely. This will cause overheating, resulting in a drop in cell voltage that will increase the charging rate. The cell will get even hotter, creating a vicious cycle.

Jake Venter is a journalist and a retired engineer and mathematician.