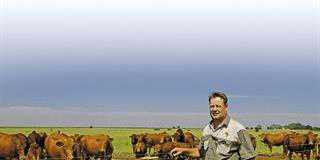

Cloete Afrikaners produces and supplies beef directly from the veld. This approach is the only way to ensure that the family farms for another 150 years, says Adrian Cloete.

Adrian, his brother Ben, his father Johan, his uncles Willie and Kobus, and his mother Dorothea run their cattle under extensive conditions on four North West farms, near Kameel, Stella, Tosca and Piet Plessis – a total of more than 10 000ha.

‘From the veld, for the veld’ is their motto, and Cloete Afrikaners seeks to establish a sustainable and ethical business model that can be adopted by others.

READ Bonsmara infused Afrikaners: enhancing performance

Adrian is chairperson of the Grass-Fed Association of South Africa (GFASA), established in 2014. Members produce free-range grass-fed beef, free from hormones and antibiotics, and the GFASA has a definition as well as a national minimum standard for free-range, grass-fed meat.

Since it involves direct marketing of a certified product, the grass-fed system is the only way a producer can become a price-maker, says Adrian. This is in contrast to the conventional system where one is forced to be a price-taker.

According to Adrian, the market increasingly demands grass-fed animals, full traceability and humane slaughter.

Certain consumers are willing to pay a premium for a product that meets these criteria. As a way of ensuring sustainability, Adrian has invested in marketing directly to consumers.

“I’m accepting the role of pioneer and overcoming the start-up challenges,” he explains. “But I don’t mind paying for it now. Our aim is to provide what consumers want, and supply directly to them.”

The four Cloete farms run approximately 750 breeding cows, split between registered stud animals, commercial Afrikaners and crossbreeds. Grazing is predominantly on sweetveld, supplemented by buffalo grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), wool grass (Anthephora pubescens) and finger grass (Digitaria eriantha) pasture.

All grazing land is managed along the same principles. For example, the farm Kromlaagte, near Stella, is divided into camps of between 50ha and 100ha, and rotated in a four-camp system in which two of the four camps are rested for an entire year.

The other two camps are grazed alternately in a six-week rotation, or until the grass again reaches the three-leaf phase.

Holistic approach

“After completing a holistic management resource course years ago as well as more recent courses with the Savory Institute, we follow a holistic approach,” explains Adrian.

“We get together and conduct grazing assessments in detail, discussing carrying capacity and cattle movement. We look at dry matter versus green growth and shoots. We then decide how much forage per animal, or animal-days, are left, and calculate our stocking rate/animal-days/camp accordingly.”

“We get together and conduct grazing assessments in detail, discussing carrying capacity and cattle movement. We look at dry matter versus green growth and shoots. We then decide how much forage per animal, or animal-days, are left, and calculate our stocking rate/animal-days/camp accordingly.”

The family also consults rangeland scientist Riaan Dames from Best Farmer on veld and pasture management.

“Even in the current drought, with our system we only sold cattle that were marketable, as usual,” says Adrian.

“We had no need to cull and now stock at five to six MLU/ha, in contrast to my grandfather, who for many years followed the system promoted by extension officers who saw 7ha/MLU as the ideal.”

Before switching to their current system, they stocked conservatively and had an excess of old dry grass in the camps.

“We also had low production. Changing our grazing approach over the past four years has made a real difference,” says Adrian.

“It’s not just about veld management. We now also ask other questions. What are the economic and ecological implications of using a different bull? Would a different or a specific bull take us further or closer to our breeding goal? Does it comply with our ethics and financial goals? What will be the effect on reproduction if we move our cows to another camp?

“Reproduction is the most important trait in our cattle. That’s why we use Afrikaners. They’re extremely fertile and

have the natural ability to survive on the veld. We breed with the end- goal in mind, which means that beef produced on the veld should not be seen only as a commodity, but as an essential part of the consumer’s daily diet. It should be a high-quality product that the consumer favours.

“Cows must calve annually and produce enough milk, maintain themselves and their calves on the veld and reproduce easily.”

Producing good bull calves is one of the main goals, as rearing steers on the veld is always an option. Steers are preferred to intact bull calves in large herds – they are easier to manage in a group, and produce better quality beef.

“We run multiple-sire breeding herds, usually three to five bulls to between 110 and 120 cows,” says Adrian. “It ties in with our grazing management plan. We have large camps and need large herds to utilise them optimally. We don’t use a fixed breeding season.”

The grass-fed model enables the Cloetes to provide a steady supply, while retaining some marketable animals to ensure continuity.

The steers receive less than 0,5% of body weight daily in lick. “This sustains them and enables us to market them off the veld at a carcass weight of between 200kg and 220kg, which is what the market favours,” explains Adrian.

“By supplementing and keeping them in a positive growth phase, we effectively gain the equivalent of a year’s production and insure they are in prime marketable condition.”

Challenges

The main difficulty of going the grass-fed route is time, admits Adrian. “As free-range grass-fed steers are only marketable at two or three years, starting a steer production system means that, in contrast to a weaner system that markets to feedlots, cash flow is initially limited.”

The three-year time-line for growing out steers does not fall into a commercial bank’s framework, which caters only for an annual/seasonal system.

“Securing a production loan to transform from a weaner to a steer production system is not that simple,” Adrian says.

READ Grass-fed beef: proven by block test

“Such a transfer should preferably be on a cash basis with minimal input cost. It’s also wise to do so incrementally over five to 10 years. We first had to enter the system. Then we had to manage our marketing. For example, last year we had to market more than one year’s stock due to the strong market demand. Now we have to catch up with fewer animals, but still meet the demand.”

However, the longer one is in the system, the easier it becomes, adds Adrian.

Determining the cost differential between a steer production system and a weaner production system is difficult. It is a calculation that few farmers have managed to get right because of all the variables involved, such as drought and veld fire, as well as the uncertainty of what the market might do in the next two years. Planning is always three years in advance.

“A breakdown of the calculation involves an either/or choice,” says Adrian. “On the same forage resource, a cattleman could potentially grow out three steers and market them as grass-fed after two years. Or he could keep a cow and her calf, sell the calf as a weaner and hope to wean another from the same cow. Which of the two options is financially more beneficial?”

This may be a difficult to decide.

“Steers need only be monitored once a week, whereas a cow has to be checked daily. Moreover, its lick intake is equivalent to that of three steers. One has to calculate every cost.”

Trace to know

The Cloetes are implementing a full traceability system in which each animal’s digital ear chip number is linked to its mating, grazing system, feed flow, lick intake, health, management plan, performance information and more.

Software linked to an abattoir system can trace a carcass from farm to slaughter and packaging, and further to butchery, restaurant or supermarket. A QR code integrated into this system would enable a consumer to track the origin of the meat they eat, whether at home or in a restaurant.

“The software also assists with our breeding goals,” adds Adrian.

It tracks the movement of the animal between camps and the weaning weight of the calf. This is compared with the dam’s weight, assists with determining a breeding goal, and assesses the animal’s performance on the farm as on the hook (dressing % + block test) and even beyond that to the plate.

“It also allows us to see on how many hectares the animal has grazed to determine kg/ha and cost/ha, and will enable us to identify genetic lines with a specific characteristic such as fat content and distribution on the carcass, as well as marbling, tenderness and carcass conformation. It also comes back to the sustainability of our business model. We need a model that can be duplicated by others,” says Adrian.

The Cloetes have been supplying beef to restaurants across South Africa from Johannesburg to Franschhoek over the past two years.

Phone Adrian Cloete on 082 213 2120 or email him at [email protected].