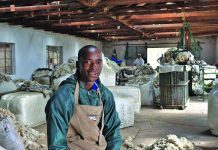

Photo: Glenneis Kriel

Dwars-in-die-Weg, near Matjiesfontein in the Karoo, has suffered five consecutive years of drought, receiving less than 60mm of its 170mm annual average rain over the past three years.

Climatic conditions appear to have normalised this year, but PF Theron, who joined his father, Wilhelm, on the family farm at the start of the drought, estimates that it can take up to 10 years for Karoo vegetation to recover its full carrying capacity.

“The problem is that you can’t accelerate veld recovery by sowing seed, because the ecosystem is highly sensitive and the vegetation extremely diverse,” he explains.

With climate change expected to result in more extreme conditions, the chances are high that the region could suffer another drought before the veld has fully recovered.

To alleviate the impact of the sheep on the veld, Theron significantly downscaled production during the drought, ending up with a mere 500 ewes on the 9 000ha farm.

This would have been financially disastrous had Wilhelm not diversified into vegetable seed production a little more than 10 years ago, a move made possible by the farm’s good-quality borehole water.

Today, this side of the operation accounts for 75% to 80% of the farm’s income. What is more, vegetable seed production complements sheep production by supplying grazing after the seed has been harvested.

“We produce onion, spring onion and carrot seed for various seed companies,” explains Theron.

“The carrots are not really nutritious, but the onion and spring onion plants supply up to three months of grazing between January and March, when there’s a general scarcity of feed due to this being a winter rainfall area.”

The only downside to this is that the sheep must be taken off this grazing at least three weeks before slaughter, as the onions badly affect the smell of the meat.

“Believe me, not doing so is a mistake you’ll only make once!” says Theron.

Sheep production

The sheep are raised under extensive veld conditions and taken to the onion and spring onion lands after the seed has been harvested.

“These lands should supply enough feed for two to three months at a stocking rate of 30 sheep/ha,” says Theron.

Because of the abundance of food, Theron uses this time as a mating season, placing one ram with 25 ewes in the onion lands. The lambing season then starts around June, when there is normally plenty of natural grazing.

Ewes that fail to raise a lamb during this cycle are placed with a ram in August while on the veld. These ewes lamb in January, when the sheep are placed on the onion lands again.

“I can’t afford to cull ewes that don’t raise a lamb, as it’s impossible to know whether they lost a lamb due to predation or because they’re poor mothers,” says Theron.

“We lose up to 30% of our sheep every year due to predation, with black-backed jackal and caracal being the main problems even though the farm is surrounded by jackal-proof fencing.”

Ewes are scanned 60 to 90 days after being placed with the rams, irrespective of the mating season. Those that failed to conceive are culled.

Thanks to the high nutritional value of the Karoo bush, the sheep receive no supplementary feed. Theron does, however, plant dryland oats where vegetable seed was planted previously, depending on the availability of soil moisture. The sheep graze the oats or the crop is ploughed in as green manure.

Lambs born in June are sold in November, and those born around January are sold between May and June under normal conditions. “We’ve been forced to sell lambs earlier during the drought to ensure there’s enough feed for the core flock,” notes Theron.

He plants about 20ha of onions and spring onions and 5ha of carrots each year, with the area under production being rotated to prevent a build-up of soil-borne diseases. The varieties also need to be planted at least 5km apart to prevent cross-pollination.

“You can plant carrots after onions, but onions should only be planted on the same land once every four years,” explains Theron.

“We take soil samples in October to November to identify nutritional imbalances and deficiencies before planting. Our soil is highly variable, so we try to get as great a mix of different soils as possible in the sample. Deficiencies and imbalances are then addressed before planting.”

As the water on the farm is brackish, Theron usually adds gypsum a few weeks before planting to address potential salinity problems.

Labour-intensive

Production is extremely labour-intensive, but conveniently spread across the season.

“During the production season, we employ between 30 and 70 seasonal workers, and they need to help with everything from planting to weeding and harvesting of seed,” says Theron.

The soil is ploughed up to 40cm deep and loosened with a rotavator to ease planting.

Spring onion bulbs are planted between February and March, depending on the variety. Seed is harvested up to six times every 10 days, from two weeks after the spring onions have been planted.

Onion bulbs are planted from April to May and are ready for harvest from Christmas to New Year, whereas the carrots are planted from June to July and harvested from the start of January up until the end of February.

The lands are under drip irrigation, as this is the most efficient way of delivering water and fertiliser to the plants. Its main drawback is that Theron has to remove the dripper lines each time after use.

He uses permanent and tape lines. The former can be used for up to 10 years, but need to be checked before being installed on a new land. Tape lines have to be replaced each season, but require less care and maintenance as they are used only once.

The onion plants are planted 8cm apart in the row and at an inter-row spacing of 30cm, with a dripper line spaced in the middle of each row. The drippers are spaced 30cm apart and supply water at a rate of about 2ℓ/hour.

The carrots are planted the same distance apart, but with 18cm inter-row spacing. Each row has its own dripper line, with drippers spaced 20cm apart and delivering 1ℓ/hour.

The volume of water applied ranges between 250 000ℓ/ha in winter and 400 000ℓ/ ha in summer, based on soil moisture, climatic conditions and the physical appearance of the plants.

“In winter we might irrigate a block for four hours once a week, and this could increase to five hours every four days in summer,” says Theron.

Power sources

The farm does not have access to Eskom power, and energy is generated from solar panels, Lister Petter engines and a diesel generator.

“The diesel generator works out more expensive than the solar power, but is required where there isn’t enough sun,” says Theron.

At the moment, he uses three Lister Petter engines, ranging from 8kW to 20kW, and four sun pumps ranging from 3kW to 5kW to pump water and run his irrigation systems.

The fertigation recipe has been developed to accommodate the plants’ nutritional demands at various growth stages, and are tweaked when deficiencies are identified.

With the drought, the region has been relatively free of disease and insect problems.

Theron nonetheless scouts the lands regularly for signs of problems and addresses these timeously. Production depends heavily on cross- pollination, so he plants male and female plants in the correct ratio and relies on bees to do their work.

“You can have the most amazing looking plants, but it won’t mean a thing unless they’re pollinated. I own 40 beehives and rent an additional 150 hives during the season,” says Theron.

Email PF Theron at [email protected].