In New York, the baseline for the World Food Programme’s (WFP)comparative cost analysis, a simple plate of bean stew costs US$1,20 (about R16) to make, or 0,6% of a New Yorker’s average daily income.

Using this as a baseline, the WFP then determined how much an average person in New York would have to pay for the stew if he or she spent the same proportion of daily income as someone in another country.

READ Food prices expected to continue fluctuating in 2018

To determine the cost of a plate of bean stew in various countries, WFP economists calculated the cost of a standard meal of beans and pulses in the respective countries, paired with a locally preferred carbohydrate such as rice or cassava, priced it on a local scale, then compared it with the average daily budget derived from national GDP per capita figures.

Thus, if a New Yorker had to spend the equivalent proportion of income as someone in South Sudan, for example, the same meal would cost him/her US$321,70 (R4 400). The reason for this is that 155% of Sudanese average daily income is needed to buy a simple plate of food!

Similarly, in Nigeria, the stew costs 121% of average daily income, the equivalent of US$200,32 (R3 000). In Deir Ezzor, Syria, it is 115% of average daily income, or US$190,11 (R2 600) for the New Yorker, while in Malawi, the bean stew would cost 45% of the average daily income, or US$94,43 (R1 300).

There are many reasons the same plate of food might cost a day’s wages in one country and a handful of small change in another. Most relate to the complex network of relationships that form pathways along which food travels from the people who grow, raise or catch it, to those who buy, cook and eat it.

These networks can be characterised as ‘food systems’.

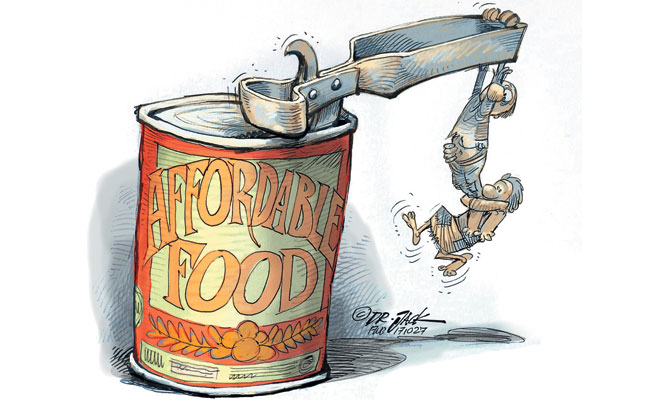

The spectre of almost 800 million hungry people globally, and the vast discrepancy in the cost of basic foods relative to income, suggests that food systems do not meet the needs of a large part of society.

Even in stable contexts they can be seriously flawed. Conflict, political instability, poor roads and extreme weather can disrupt them even more. The implications for hunger, both temporary and long-lasting, are real and urgent.

Short-term concerns include the volume, value and quality of food in the supply chain, the cost of packaging and transport, and whether it is possible to deliver food to people in need.

In the longer term, political, social and economic conditions, as well as climate trends, must all be taken into account. How these interact determines the location, volume and cost of food production and processing, which in turn affect whether the food available to vulnerable populations is affordable and safe.

More vulnerable

Three main problems have been identified in food systems. If inadequately addressed, they can generate chronic hunger or make food systems more vulnerable to shocks.

The lean season problem: When crops fail or shocks occur, poor families in urban and rural areas lack the resources to meet their food needs and adopt desperate measures, including cutting back on meals and eating less nutritious food.

The good year problem: Insufficient capacity to store, market and transport food surplus causes prices and quality to drop. This leaves farmers unable to put their produce up for sale at a premium when demand is highest, leading to food waste and spoilage, and increasing market volatility.

READ Smallholder co-operatives combatting food waste

The last mile problem: The rural and urban poor are geographically, economically, socially and politically isolated and hard to reach. When nutritious food is available near them, it is often too expensive for people living hand-to-mouth to afford.

The resilience and overall performance of food systems hinges on how effectively these problems are handled. The key findings of the WFP’s Fill the Nutrient Gap analysis have been widely reviewed to identify ways to improve access to nutritious foods.

While country contexts vary, it is, nonetheless, possible to identify examples of sector-specific priorities for governments, UN agencies, development partners, civil society, the private sector and academia.

Food assistance must be innovative and pragmatic. There is an acute need for concentrated efforts to create beneficial ripple effects that address the root causes of hunger. Only in this way can we reduce the number of hungry people.

Partnerships must be formed to:

- invest in market-friendly food assistance that delivers safe and nutritious food to targeted groups, is accountable to beneficiary populations, and enjoys strong government leadership;

- confront the political causes of vulnerability and hunger;

promote a sharper research agenda to develop food assistance solutions that address systemic problems, while also responding to emergency needs.

Supply chains

Strong yet flexible supply chains that can respond to shocks, whether human-induced or natural, are crucial for reducing food insecurity. Infrastructure connections between markets and smallholders need to be improved, enabling a smoother flow of goods along the supply chain.

Better access to markets and to credit facilities and insurance for smallholders will allow them to increase their output, earning and investment opportunities, resilience and knowledge base.

Other recommendations include:

- Introducing technology to reduce post-harvest losses;

- Encouraging the retail sector to become more efficient and competitive through aggregation of ordering from wholesalers;

- Communicating and cooperating with governing bodies to tackle large-scale crises.

What can farmers do?

When it comes to agriculture and the food value chain, we need to do the following:

- Ensure agriculture extension officers talk about the importance of good nutrition, diverse diets, the importance of horticulture and (small) livestock;

- Explore introducing bio-fortified crops;

- Expand and strengthen existing private (or public-private) sector initiatives to increase availability and affordability of fortified complementary foods in markets;

- Develop and implement standards and regulations for manufacturing and marketing of fortified complementary foods and snacks;

- Harmonise the regulatory framework related to staple-food fortification between national and provincial levels.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Extracted from ‘Counting the beans: the true cost of a plate of food around the world’ by the World Food Programme, a specialist unit tasked with mapping fluctuations in the price of food, and using these as an indication of the nutritional status of entire populations.

For more information, visit wfp.org.