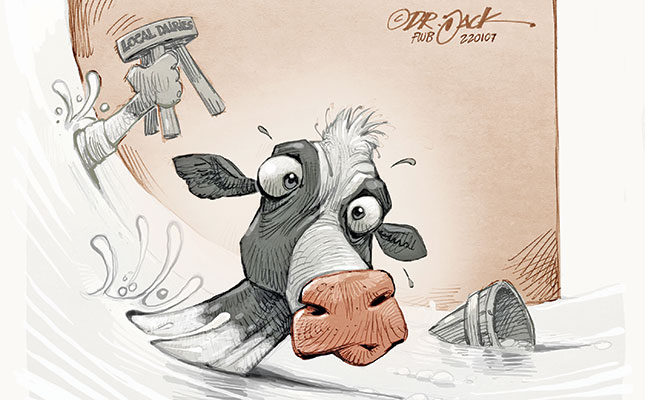

In simple terms, one of the main reasons that so many producers have left dairy production in recent years, and why those who remain have to increase the scale of their operations to survive, is low farm-gate prices for milk.

These low prices are a result of margin loss amongst dairy processors emanating from cheap (often subsidised) imported milk products that is then pushed back on milk producers.

For years, the Milk Producers’ Organisation has argued that the level of free on board (FOB) prices of imported dairy products from the EU, Ireland, Eastern European countries and the UK seems unrealistic and unfair. This is due largely to the substantial funds that subsidise farmers and dairy producers in Europe.

There are five EU funds that support agricultural and rural development, on top of the many direct payments to farmers under the Common Agricultural Policy.

These funds include the European Regional Development Fund (regional and urban development); the European Social Fund (social inclusion and good governance); the Cohesion Fund (economic convergence by less-developed regions); the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development; and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund.

Recently, subsidies for sustainable energy projects were also introduced.

Programmes and applications of these funds reduce costs in the value chains and enable European countries to make products and commodities available on the international market at reduced (unfair) prices. Subsidies are paid to farmers in Europe, as outlined in the Common Agricultural Policy.

In 2017, a total of €41 billion (about R730 billion) was paid to farmers and in 2020 this had risen to an estimated €59 billion (R1,1 trillion), an increase of nearly 15% per year.

Market-distorting policies

Fair competition between companies and countries around the world drives the optimal allocation of production factors that enable markets to discover price levels for different production factors based on demand, reflecting scarcity.

Unfair competition because of subsidies by governments distorts these markets, spilling over into improper economic policy and reduced economic growth.

In the end, it destroys a country’s ability to achieve food security or enter the export market. Notwithstanding the absence of binding competition rules within the World Trade Organization (WTO), competition concerns have long been a fundamental question within the international trading system.

And even though competition policy was deleted from the Doha agenda, anti-competitive practices continue to attract attention. Therefore, international institutions such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Competition Network, the UN Conference on Trade and Development, and the WTO actively discuss the creation of international frameworks to shape competition policy.

A striking similarity exists between the objectives of the WTO and those of competition policy laws in certain countries. The key concepts common to both are, inter alia, the promotion of an open market, the provision of fair and equal business opportunities to every participant in the market, transparency and fairness in the regulatory process, the promotion of efficiency, and the maximisation of consumer welfare.

In this article, we argue that important synergies exist between economic, trade and international competition laws and that it is reasonable to charge that a fresh reflection and overhaul on related issues are necessary when, for example, the South African dairy industry is analysed.

The prices don’t add up

Our analysis of the import data of dairy products for the first nine months of 2021 provides ample evidence to suspect foul play in the market. During this period, South Africa’s total value of dairy imports was R2,3 billion. For illustrative purposes, we conducted an analysis of only two imported products, Cheddar cheese and UHT milk.

Ireland and the Netherlands were jointly responsible for 91% of all Cheddar imports into South Africa between January and December 2021. To assess the ‘fair pricing’ of these imports, we compared the estimated cost of the milk needed to manufacture 1kg of Cheddar cheese and compared this with the FOB price that was paid for the imported Cheddar.

In both instances, for Cheddar imported from Ireland and the Netherlands, the cost of only the milk component exceeded the FOB price paid by the importer in South Africa by between 6% and 12%.

A backward estimation of the landed FOB price of Cheddar versus the cost of the milk component alone leaves no money available to cover the following: Cheddar-manufacturing costs, packaging material, storage costs, time value of money during storage, transport to and offloading at the harbour, and agents’ commission. There is also no profit margin available for the manufacturer.

Who then carries these costs and profit margin? One can only speculate that programmes from the EU funds provide cost-saving opportunities that enable European manufacturers to remain viable and profitable.

This, however, is at the expense of many dairy farmers across the world, mostly in poorer countries where money for subsidies is not available.

To drive the point home: it is easy to state that an industry must be able to compete with imported products and brush over it with “don’t worry, the market will sort it out”, but that is too simplistic.

What is missing are the words ‘fair-priced imports’, and this resonates well with international law on competitive behaviour.

In our analysis of UHT milk imported from Poland, which was responsible for 74% of all UHT milk imports for the period between January and September 2021, the price margin between the price paid to farmers and the FOB price for the imported milk also seems suspiciously narrow to cover all other costs.

On average, over the nine-month period, the margin left to cover all other costs was R2,90/ℓ. Other cost components of UHT milk manufacturing (excluding the cost of the unprocessed milk) include:

- Manufacturing: R1,31/ℓ;

- Packaging: R1,95/ℓ;

- Transport from Warsaw to port of export, Gdynia: R0,25/ℓ;

- Agents’ commission: R0,08/ℓ; and

- Profit margin: R0,30/ℓ.

When taking these costs into account, there is an average shortfall of almost R1/ℓ. Other costs not included are the time value of money during storage, storage costs in the processing plant, and losses. Moreover, the composition of the primary dairy industry in Poland, with a small dairy herd on each farm, raises the inevitable question of the financial viability of a herd of 50 dairy cows.

The examples of Cheddar cheese and UHT milk exhibit sufficient evidence to question

the fairness of using imported dairy product prices as a basis to determine whether the local milk market is competitive.

Downstream value chain role players (the secondary and tertiary industries) that use this distortion as a departure point in price negotiations have severely damaged the primary dairy industry, and will eventually destroy the industry in South Africa if this modus operandi continues unchallenged.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Email Bertus van Heerden at [email protected].