Disinformation and misinformation seem like far-removed concepts that do not concern farmers. But everyone in the agri food chain has a ticket in what can be called the disinformation lottery. If you’re lucky, your ticket number will never come up. If not, you’ll need to learn very quickly how to navigate a disinformation storm.

There are three legs of this stool: misinformation, disinformation, and activism.Misinformation is when information is shared that is false but which the sender did not necessarily realise was false since they did not fact check. Everyone is susceptible to spreading misinformation, since social media is a hotbed of passing on such information.

Disinformation is when someone actively decides to upset, disrupt, or destroy something by publishing information that is known to be false.

Activism is on the far end of this spectrum and is general engagement from different types of civil society organisations for or against different things.

These are all interconnected, as misinformation feeds disinformation, which feeds activism.

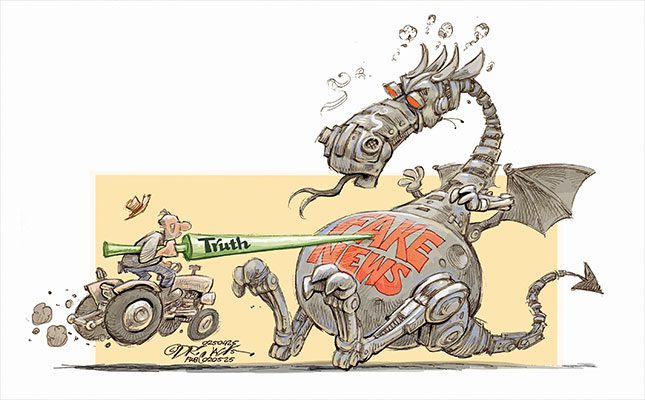

Artificial intelligence (AI) is currently being used in the communication space to effect some very undesirable impacts on agriculture. It can create content, spread it, disseminate it, and respond to it faster than we could ever hope to correct it. But we can use the same tools to distribute truth.

Working out how to do this is going to become critical, especially if we want new technologies and innovations to survive. Governments used to take decisions based on scientific facts and evidence, but today they also look at a whole host of different factors, which can include disinformation.

Everyone is vulnerable

New technologies require thorough communication strategies from the outset to prevent misinformation from halting commercialisation.

We often hear about innovation, science, and technological advancement in agriculture. However, what we don’t often hear is how many of those advances in agriculture have been contested and lost the fight in the world of public opinion.

Technophobia is not new and has existed since the printing press was created centuries ago; electricity was resisted violently for many years.

The most recent example is that of genetically modified organisms [GMOs]. No matter how much new science we throw at the GMO situation, it doesn’t seem to make any difference.

Actually, if you look at the statistics on public opinion on GMOs and science, they’re almost inversely related. The more science you publish, the worse public opinion seems to get.

With technology, the issue is not so much disinformation but technophobia due to the fear of the unknown.

Looking at how disinformation plays out, one can look at the example of Arla Foods in the UK. Last year, the company announced that it would start using a feed additive for its dairy cows that would reduce methane gas emissions by 35%. This was part of the company’s sustainability drive to comply with EU laws.

The information was publicised as a big win for the company and sustainability. But within

48 hours, it had to stop the project because it came under public attack. Suddenly there was a viral online campaign saying that this feed additive was toxic and should not have been authorised. The campaign stated that the additive would kill the cows and the children who drank the milk.

Within 24 hours after Arla’s announcement, people were posting videos of themselves

online pouring milk down the toilet. Within 36 hours, there were petitions to three supermarket chains to boycott all of Arla’s products.

Misinformation and disinformation are not just noise; they have real-world consequences, and we need to think about this as an industry, all the way down to a farm level.

The local risk

The risk of disinformation around agriculture is generally high because food is extremely personal. South Africa has additional risks that make it particularly vulnerable to disinformation campaigns.

Disinformation around land, expropriation, food security, and foreign corporate control of agriculture tap into existing fears and political narratives around agriculture. This is due to historic political sensitivities around land, food security, and foreign corporations. Politicians have been shown to take advantage of the agricultural narrative when it suits their purposes.

Furthermore, Facebook and WhatsApp are the two biggest channels for disinformation. South Africa has a high penetration of mobile phones, which are sold with these apps pre-installed. Social media platforms are one of the biggest drivers of fear and disinformation because their algorithms are tuned to promote emotional engagement. Factual posts don’t reach as far.

Adding to this is that South Africa has extremely low media literacy. This creates the perfect conditions for disinformation.

What can we do about it, and how can we make a positive difference? Misinformation and disinformation are so successful because they meet with apathy.

A proactive approach

Arla Foods’ response was to issue multiple statements and then mobilise a large number of individuals, including farmers, other stakeholders in the supply chain, consumers, and authorities to tell their side of the story. They told their story continuously for 10 days.

Like many misinformation moments, it spiked, and then just as fast as it came, it went.

Why? Because there was pushback. There was an alternative narrative. And all of those people who were initially interested just moved onto something else. This speaks to the theory of standing up to a bully. If you do, the bully often backs down. If you don’t, the bullying just gets worse.

A proactive approach includes gaining digital literacy and AI awareness, because you need to know how to fight. The biggest thing preventing pushback on disinformation is fear and hesitancy.

Most people will want to respond, but they’re held back by doubt over how and what they communicate from there. Arla Foods was completely transparent in their communication, which helped them tremendously.

In the US, there’s an organisation that, for the past 10 years, has been training

35 farmers each year in media and social media literacy. They want farmers to act as envoys, messengers, and have a voice.

Big corporations are usually the least credible voices in this space. Furthermore, their communication often has to go through a legal team, which makes it mostly incomprehensible for anybody who’s trying to read it. What makes a difference is the human stories – real people telling real stories.

But communication needs to be managed. This is where you can use AI in your favour. AI can help you identify the main areas you could be attacked on. It could be a fake health or safety claim, or a supposed environmental benefit.

The most powerful misinformation and disinformation mixes facts with falsehoods. If the whole story is completely fake, it tends to look obvious. Activists normally always have a point that may require you to look yourself in the mirror about some of your practices.

The next step is to have an early detection system in place, which includes proactive social media monitoring. AI can help you identify fake content.

After that, you need a plan for when a crisis hits, which ChatGPT can also help you create. It should include being able to prepare official statements backed up with data.

There should be a strategy for identifying credible journalists or industry leaders that can help discredit fake news. Aim to get as many third parties involved as possible to tell your side of the story. You’ll likely have to pay for amplification, as facts don’t spread as fast as disinformation.

The agri food chain is no longer just about the agri food chain. It is about the communication of and around the agri food chain. AI is fuelling disinformation, creating speed and scale to have an impact that we’ve never seen before. It is empowering amateurs to become professionals and giving power to a small group of activists and dissatisfied individuals.

Defending truth in agriculture is everyone’s responsibility, and it starts today. The future success of farming will, in part, be about good communication.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Advocacy Academy is an online education platform designed by public affairs professionals for public affairs professionals. It is aimed at empowering public affairs professionals by offering instructional videos, toolkits, templates and guides with a practical focus on key knowledge, skills, tasks and deliverables.

For more information visit advocacy-academy.com or Email [email protected], or Alan Hardacre at [email protected].