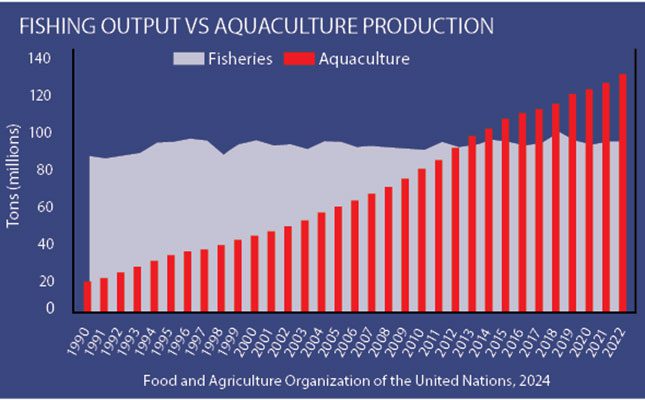

The output of seafood (both freshwater and marine) from global fisheries stagnated at around 90 million tons a year in the 1990s and, despite heavy investment into technology and subsidies, fishermen are unable to catch more fish.

This is simply because the resource is already fully exploited and additional fishing pressure simply reduces the future catch by targeting smaller and smaller fish.

Against this backdrop, the world’s human population has grown from 5,3 billion in 1990 to eight billion in 2022 (World Bank, 2024). Therefore, we require increased tonnages of fish.

The growing shortfall between the stagnant supply of wild fish and increasing demand for fish to eat (and to feed our farmed animals) is the impetus that is pushing the rapid global growth of the aquaculture industry.

The graph on the opposite page demonstrates this. Fisheries output has been constrained since 1990, while aquaculture has grown sevenfold over the same period.

About half of the aquaculture output is fish, with the other half being a combination of molluscs, crustaceans and aquatic plants. This rapid increase in fish farming has not been equally distributed across the globe, with Southeast Asia and selected other countries developing massive industries while other parts of the world languish far behind.

China farms about 60% of the fish produced globally. Within Africa, Egypt produces more than 1,5 million tons of fish annually (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024), which is roughly double the rest of the continents’ combined output.

Industry dominance

How have these countries gained such incredible command of the industry? There are several factors at play, but it seems that one of two approaches has dominated in almost every case: either the demand for fish by a population that consumes a large portion of fish in their diet (China, Egypt, Philippines, Indonesia) or commercial investment (Chile, Norway).

In both cases, the industry has grown with the support of a government that creates an enabling environment for commercial developers to make investments and enjoy a profit from their labour.

Low growth in sub-saharan africa

Across much of sub-Saharan Africa, aquaculture has failed to grow to its full potential despite there being huge demand for fish. Logistics challenges were a constraint, but these have been addressed and are less important in many countries.

Lack of access to quality genetic material along with a shortage of technical and business skills remains a hurdle throughout.

A huge factor that hobbles aquaculture’s ability to grow is the availability of affordable, quality fish feed. In countries where dedicated aquaculture feed manufacturers have invested, the result is a rapid growth of the industry. However, it must be quality feed and the price point needs to be correct.

When we speak of the cost of fish feed, the price tells only a part of the story. What is more important to understand is the cost of feeding per kilogram of growth. The diagram on the right provides a visual impression of what happens when fish are fed on a farm.

Some of the feed may be wasted if the fish are fed too quickly or too much feed – this is unacceptable and controllable by appropriate management.

A portion of the feed is utilised for metabolism; where fish are farmed under optimal conditions, this portion will be at its lowest but it is unavoidable. Some of the feed will be excreted as faeces.

The proportion of the total is a function of the quality of the feed: the higher the feed quality, the lower this portion will be. Whatever remains is then available to be laid down by the fish as growth, and the efficiency with which the feed converts to growth is again a function of the quality of the feed.

The efficiency with which feed is converted into growth is indicated by the feed conversion ratio (FCR), which is simply the ratio of feed fed compared to growth achieved over a period of time.

On a well-managed fish farm using high-quality feed, this ratio can be as low as 1:1 (bear in mind that the feed is dry whereas 70% of the mass of the fish is water), whereas the norm is around 1:1.3, meaning that 1,3kg of feed is required to achieve 1kg of growth.

Indicating feed usage efficiency, the FCR is a fantastic gauge of overall farm performance. If the FCR is poor, or worsens, then management knows something on the farm is suboptimal, providing the early warning indication that prompts investigation to identify and address the cause.

When the FCR remains consistently attractive the management can assume the farm is running well, and this in turn has a profound impact on the viability of the farm.

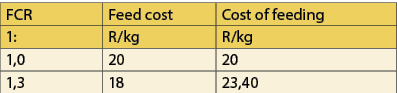

The table below compares the cost of rearing 1kg of fish under identical farming methods and infrastructure, using two different feeds. Feed A is high quality and costs a bit more but achieves an FCR of 1:1, resulting in a feed cost of R20/kg on every fish reared.

Feed B is slightly lower quality, offers an FCR of 1:1.3 and results in the cost of feeding being R23,40/kg of fish reared. On a farm producing 500t of fish annually, this amounts to a difference of R1,7 million a year!

Feed generally constitutes 50% of the operational cost on a fish farm and as such it is extremely important that we manage the facilities and protocols to ensure optimal feed utilisation. Feed usage efficiency should also be maximised to ensure we optimise the margin we make on our fish farm.

Leslie Ter Morshuizen designs and builds fish farms across sub-Saharan Africa, trains farmers to manage them optimally and has run his own operations. He is the founder of Aquaculture Solutions. Call him on 083 406 0208, or email [email protected].

Get trusted farming news from Farmers Weekly in Google Top Stories.

➕ Add Farmers Weekly to Google ✔ Takes 10 seconds · ✔ Remove anytime