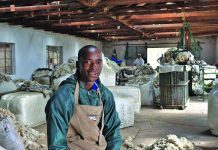

Photo: Annelie Coleman

Koenie Kotzé, who farms between Douglas and Prieska in the Northern Cape, is a keen livestock breeder. He runs Bonsmara and Dexter commercial cattle herds, as well as small-stock studs, including Savanna and Boer goats, and Dorper, White Dorper, Van Rooy and Blackhead Persian sheep.

His interest in breeding animals has also resulted in a flock of highly sought-after exotic Persians (which are not considered for stud breeding). In addition, he breeds four- and five-horned sheep to preserve their genetics.

Tricoloured Persians

In one of his most ambitious endeavours to date, Kotzé has succeeded, through careful selection, in breeding Persians that are red-speckled, black-speckled, blue-speckled, pink-speckled and white-speckled respectively, as well as two tricoloured types. The tricoloured combinations consist of black, brown and white sheep, and blue, pink and white sheep.

“All the colours are sought after by buyers in the Middle East, but the tricolours are the

most popular. White and red speckles are also gaining popularity. My wife Marina and I like the black, brown and white combinations in particular,” says Kotzé.

The sheep are kept as a leisure pursuit in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and competition amongst buyers is intense. Owners are keen to outdo each other with new and more impressive colour nuances, tones and shades, according to Kotzé.

Persian sheep are ideal for hobbyist farmers as they are small, calm, naturally polled and do not require shearing. Although the exotic Persians are not recognised as a separate breed by the Blackhead Persian Sheep Breeders’ Society of South Africa, all the animals earmarked for the export market must meet the minimum breed standards as set out by the society.

Before being exported, animals are examined by Persian society inspectors for diseases according to the importers’ protocols. Royalties are paid to the society for each sheep exported.

Complex genetics

The Persian breed is of ancient Middle Eastern origin, where the sheep once thrived in semi-arid desert areas. Forerunners of the Blackhead Persian arrived in South Africa in 1869 purely by chance. A ship damaged by a storm at sea put in at the Cape.

On board were four Blackhead Persians, a ram and three ewes, destined for slaughter. They were taken to Wellington, where the breed was further developed.

The initial group had black heads, but produced some progeny with red heads. In 1930, the Blackhead Persian Sheep Breeders’ Society of South Africa was formed. Blackhead Persians were registered as purebreds in the first South African Stud Book in 1906.

Kotzé has always been interested in genetics, and enjoys “playing with them in a responsible way”, as he puts it. However, colour inheritance in sheep can be complex.

Chromosomes are made up of a series of genes. Genes are sequences of nucleotides (amino acid combinations) and take on different forms, called alleles. The alleles are located at the same position (or genetic locus) of a chromosome. Sheep have 27 pairs of chromosomes.

When the egg and sperm unite at fertilisation, the genes of a pair recombine in the offspring. The new pairs of chromosomes created in this way determine the genetic make-up and characteristics of the offspring.

An uphill battle

Kotzé says he first became aware of the value of multicoloured Persians about five years ago. He sold a red-speckled Persian ram to a breeder in the Western Cape for R17 000, who eventually sold the same animal to a breeder in the UAE for R160 000!

“I learnt a valuable and expensive lesson, and then embarked on the breeding of painted sheep as an additional source of income. At the time, we found ourselves in the grip of one of the worst droughts ever in South Africa, which had a heavy impact on the farm’s cash flow.”

It was not an easy task to establish all the colour variants, and Kotzé took years to develop the various genetic strains now present in his flock. For example, he went through quite a struggle with the development of the blue-and-pink-speckled variety.

He even experimented with a grey Swakara ram in his quest to meet the challenge, but to his frustration it did not have the desired result, as the progeny merely resembled a run-of-the-mill Persian-Swakara cross.

Kotzé eventually succeeded in finding a blue-speckled ram from a breeder in Kenhardt, and this put him on the right genetic track.

“I put the blue-speckled ram to one of my red-speckled ewes and she gave birth to a few pink-speckled lambs. To this day, seeing pink-speckled lambs being born is rare,” he says.

Breeding challenges

It was difficult to breed sheep with a blue, pink and white combination. However, when Kotzé put blue-and-pink-speckled rams to blue-and-pink ewes, some lambs carrying blue, pink and white speckles were born, although they remain few and far between.

Meticulous selection and animal pairing have nevertheless enabled him to establish seven colour strains so far.

“There’s no room for complacency in any farming concern, and I’ve therefore set myself the goal of breeding sheep with four colours in future. This is important for retaining and expanding my market,” he says.

Kotzé exports his sheep, usually a group of ewes and a ram of the same colouring, through an agent. The animals are kept in a quarantine facility for up to 30 days, depending on the protocols of the importing country.

During the period of isolation, they undergo intensive health assessments. They are then transported by air to their final destination.

According to Kotzé, there is also a strong demand for exotic, coloured Persians in Namibia, but the trade between South Africa and its neighbour was seriously affected by the closure of borders because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The recent reopening of the border will, in all likelihood, add new impetus to the exotic Persian industry. Kotzé has also received inquiries from prospective exotic Persian breeders in Botswana.

Kotzé’s advice to prospective breeders and exporters is to make sure they “have the money in the bank” before following through with any transaction. Although painted Persians are not recognised as a separate breed, demand for them is on the increase. This is especially true of buyers in Namibia, where the colour variants compete in the show ring.

“The painted Persians retain the characteristics of the breed and should never be considered inferior to the rest of the breed. There is, for instance, no difference between the slaughter weight of coloured sheep and traditional Persians.

Even under the extremely taxing conditions caused by the continuing drought in our region, these animals perform just as well as the rest of my Persian herd,” he says.

Additional income

According to Kotzé, the painted Persians have added much-needed value to his business, especially as the region has been subject to a 12-year drought. Unfortunately this is not yet over, and on-farm income has been on a steep downward trend.

The new enterprise of exporting painted Persians has enabled him to meet cash flow demands and has given his farming concern some reprieve from the effects of the drought.

“We’re still experiencing drought, as a matter of fact. It goes without saying that the new opportunity of breeding and selling exotic Persians was a godsend,” he says.

Email Koenie Kotzé at [email protected], or Marina Kotzé at marinakotzé@gmail.com