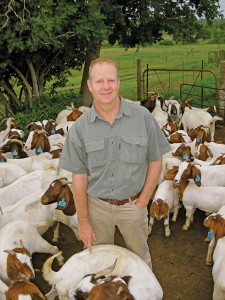

Photo: Courtesy Johan Steyn

The Boer goat industry in South Africa

To what extent is the Boer goat industry important for SA agriculture?

South Africa is not a very agriculture-friendly country. Its northern neighbours have a much more favourable climate. Large areas of the country receive an average annual rainfall of less than 400mm, which is classified as a semi-arid environment.

The Boer goat is bred to thrive under extensive livestock farming conditions in hot, arid environments where the quality of grazing is poor. The breed has the ability to convert poor-quality forage into meat at a very low cost, enabling livestock farmers in these arid areas to farm commercially.

Cultural practices among black and Indian communities provide a steady market for live slaughter Boer goats, with KwaZulu-Natal being by far the largest market for Boer goats.

READ:Emerging farmers must be empowered

South Africa imports large numbers of Boer goats from Namibia at low cost. Can our farmers compete with this market without suffering losses?

There are unscrupulous importers of Namibian Boer goats who contravene South African import legislation by selling goats imported as slaughter animals, as breeding stock. This depresses the market price of quality breeding animals produced by SA farmers. Local buyers believe they can buy top-quality genetics for between R900 and R1 200 on auction. This simply isn’t possible.

By law, animals imported into South Africa as slaughter animals have to be slaughtered within a specific number of days of crossing the border. When I enquired what this period was, the agriculture department declined to give an answer, insisting on a written query that its communication department would reply to.

The second problem is that there’s a current trend amongst commercial SA farmers to pamper their goats, providing stall feeding and entering them in shows and auctions. These animals require expensive inputs, negatively affecting profitability. The Boer goat was never bred for this; it was bred to be fertile, hardy and adaptable with good mothering abilities – requiring very low input costs to farm profitably.

Should our farmers look at other markets?

There is a good market for slaughter goats in South Africa. As with all businesses, prices vary according to the time of year and prevailing economic conditions. Generally, however, the market for live slaughter animals is steadily increasing. The urbanisation of South Africa’s population has seen other markets for Boer goat farmers opening up. These include Boer goat meat – chevon – being available in butcheries and supermarkets supplying speciality restaurants and the health-conscious consumer.

To my mind, the latter has great potential, considering that Boer goat meat, after venison and ostrich, has the lowest cholesterol levels, is lean and contains high levels of iron and other nutrients. It’s also farmed extensively, so no growth stimulants or supplements containing animal protein are fed to the animals. I believe these are the new undeveloped markets awaiting the Boer goat farmer.

BFAP statistics show that around 430 000 families in South Africa own goats. One gets the impression that these families are not generating a sustainable income from them. What are the reasons for this?

This is proof that small-scale farming is unsustainable and uneconomical, and gives the lie to the government’s plans to establish small-scale farmers. Livestock and crop farming require volume and economies of scale to be profitable. A family of four, for example, cannot survive on the income generated by 20 to 50 goats. Modern, commercial stock farming practices, including rotational grazing, planned production cycles and effective animal health programmes, must be combined with good genetics to maximise the revenue generated by a livestock farming enterprise. This is simply not happening.

A purebred Boer goat, combined with good management practices, should deliver weaning percentages of around 160% to 170% and a marketable slaughter animal weighing between 30kg to 40kg within nine to 10 months. In practice, it often takes communal or small-scale farmers 22 months to 26 months to get their slaughter animals to these weights.

Training, mentorship and economically viable farming units can go a long way towards rectifying this problem for farmers who have a passion for their Boer goats.

Can the industry make a meaningful contribution to the development of emerging farmers?

Boer Goats South Africa, an independent organisation that provides information and expertise aimed at sustainability has trained more than 2 000 farmers in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and other African countries on profitable Boer goat farming over the past nine years.

Most of these learners have paid their own way to attend the courses and buy training materials. The Free State agriculture department took the right approach some years ago when it insisted that more than 100 learners attend these courses prior to receiving start-up flocks of goats. Boer Goats SA will also soon have online courses and ebooks available to give all Boer goat farmers access to this knowledge base.

However, no amount of training or development can turn a non-viable venture into a viable one. This is an economic reality. The learners should have a passion for Boer goats and have gone through a selection process where potential farmers are identified before going for training.

The training should be followed up by farm visits and other mentorship programmes until the farmer can stand on his or her own feet. Rather than granting money to non-viable farming enterprises, the government should work with organisations such as Boer Goats SA to train new and existing farmers on sustainable and viable Boer goat farming.

Input costs for Boer goat production are less for sheep, which makes the industry more accessible to emerging farmers. Is government looking at a strategy to help the industry and establish a market for emerging farmers?

There have been a number of initiatives launched whereby some form of ‘collective grower’ scheme is supposed to supply supermarkets with goat meat. The problem with these initiatives is that they start at the top rather than at the bottom – with the farmer. A farmer with no training, poor-quality animals and little or no animal health programme, and who suffers high stock losses from mortalities and stock theft doesn’t remain motivated for long.

These are the areas where the government could possibly become involved – but they should not try to establish 50 families on 250ha of land, as was attempted in North West some years ago. This dooms people to a life of poverty and misery.

The market already exists. New farmers should be provided with the basics upon which to build a business to supply that market. This consists of training, foundation stock and essential inputs, as well as meaningful mentorship until such stage as the farmer is independent and productive. The process should be aimed at a selected group of dedicated, proven farmers operating on economically viable farms. The current approach by government is too wide and applied for the wrong reasons.

The Boer goat industry doesn’t seem as regulated as, for example, the beef and sheep industries. Is there room for better regulation and will this help it grow?

Your observation is correct, and there are moves afoot to better self-regulate it. While change in the interests of improvement is good, change for the sake of change is not. A few of the aspects that can be improved are breed standards and consistent implementation thereof, development of a functional, easily manageable grading system, and farmer participation in performance statistics and genetics recording by bodies such as SA Stud Book.

These initiatives will improve the breed by developing a database and establishing performance benchmarks to support the current predominantly visual grading system that has led to the growth of stall-feeding Boer goats. Farmers need solid performance data on which to base their decisions when buying Boer goats. A visually pleasing animal is no longer enough to ensure success as a commercial farmer.

What’s in store for the future of the Boer goat industry?

The Boer goat industry in South Africa is essentially healthy, with a steady market locally and internationally in Africa and the Middle East. However, while there’s strong demand from countries such as China, India, Nepal and Pakistan, the lack of formal protocol between South Africa and these countries precludes farmers from exporting to them.

The agriculture department does very little to expand and formalise agreements with the many potential importing countries, which constrains local producers.

Locally, the industry could look to the burgeoning packaged meat and speciality restaurant markets. These are sectors woefully serviced despite their growth. The sustainability of supply will need to be addressed, as will the logistics and grading standards. Above all, the industry must return to the breed’s core strengths of hardiness, fertility, adaptability and good mothering abilities.

These are the foundation stones of the Boer goat and diluting them will do long-term damage to the breed.

A Boer goat must thrive under extensive conditions, bucks should display a high libido, easily covering does in the veld on natural grazing with minimum inputs. They should walk long distances and convert poor-quality vegetation into healthy lean meat. Does should kid in the veld and raise the kids easily and with minimal intervention by the farmer.

The Boer goat’s low input costs are what drive the profitability of farming with the breed. This is what the commercial producer is looking for. The trend toward stall-feeding will result in substandard genetics becoming more prevalent in the breed, to its detriment.

What could the industry do to increase the local use of Boer goat meat, especially as an alternative source of meat?

Sustainable production needs to be expanded in order to meet the demands of an increasingly urbanised and affluent population. Retailers will not allocate marketing and retail space to a product that cannot be supplied consistently and according to accepted standards.

In addition, producers must take greater ownership of the supply chain by establishing standards, developing branding, implementing generic marketing and promotional campaigns co-funded by retailers, building a nutritional value and benefit database for goat meat, and communicating all this to the market.

The health food industry is an underexploited segment despite its growth worldwide. Goat meat is one of the healthiest red meats available and it can fill a gap in this market segment if marketed correctly and aggressively.

The stud market has potential for growth. Are farmers aware that exports to countries such as the United Arab Emirates is profitable?

The export market does have potential, but it’s not for the faint-hearted. Although prices are somewhat higher than those in South Africa, the risk is much higher and administration requirements significantly more onerous. The deteriorating exchange rate works in the favour of producers earning US dollars and this fact supports the Boer goat export industry to a large extent.

Much like the recent vigorous growth in the exotic game industry in the country, the Boer goat export market is maturing rapidly as participants looking for quick money are shaken out. There are already signs that the buyers are becoming more educated and less prone to scammers and gold diggers. The recent decline in the oil price has placed a significant damper on export to the Middle East but other markets seem to be less affected and demand remains good.

Why is the stud market in the Middle East so good?

In the Middle East, while many of the Boer goats do indeed form part of a commercial farming operation, a certain percentage is bought more as a hobby, a status symbol or as part of a lifestyle farm. For those bought as status symbols, grade is important to buyers, with Grades 8 and 9 stud animals being particularly sought after.

Extensive farming in many countries in the Middle East is simply not possible due to the very limited availability of any form of grazing. Much feed in the form of lucerne and pellets is imported from countries such as Spain.

In Africa, many farmers and governments import Boer goats as commercial production units or as part of cross-breeding programmes with indigenous goats to improve the quality of their flocks. Here the core Boer goat characteristics of hardiness, fertility, meat-carrying ability and adaptability weigh more heavily in the decision-making process.

Email [email protected].

This article was originally published in the 25 September 2015 issue of Farmer’s Weekly.