Photo: Lindi Botha

A hardy plant and thick-skinned fruit are two of the characteristics that make brinjals a relatively fuss-free crop to produce.

“There are no production challenges. It’s a willing grower,” says Theuns Kotzee, one of the directors of AAL Boerdery in Trichardtsdal, Limpopo.

Kotzee runs the farm in partnership with his brothers-in-law Sybrand van Jaarsveld and Louis Lategan. Production comprises papayas, jam tomatoes, peppers and brinjals, with cabbage and butternuts gradually being added to the mix.

Kotzee says that having brinjals adds an element of stability to their operation.

“You can depend on a brinjal; it won’t really drop you. But because market expansion is limited, brinjal needs to form part of a larger basket of products that you deliver to the market.”

AAL Boerdery has been cultivating brinjals for about 20 years, testimony to the dependability of the crop.

“We have an affinity for brinjals. Our family eats lots of them and there are few meals where brinjals don’t feature,” says Kotzee.

Growing conditions

Trichardtsdal’s high temperatures are well suited to brinjal production. Kotzee recalls the mercury reaching 46°C without affecting the crop. Low temperatures, too, have little effect; in winter the minimum temperature falls as low as 0°C without causing problems. All this enables AAL Boerdery to produce brinjals throughout the year.

The crop is grown on 6ha, with an annual yield of between 100t and 120t. Four to five workers per hectare are required.

The lands are arranged in cultivated blocks, and these are rotated so that the crop is planted on the same land every third year.

Soil preparation is carried out at the start of each cycle, and begins with ripping the soil in September, then allowing the land to rest for three months.

During this time, the rows are marked out and the droppers placed where the brinjals will be planted and supported. In January, Kotzee and his team disc, level and ridge the soil.

They then plant the seedlings on the ridge in double rows, spacing them at two plants per dripper. The plants are supported from week two onwards with wires attached to the droppers.

AAL Boerdery plants Black King and Shakira cultivars, chosen for their droplet shape as this makes them easier to pack.

Kotzee says that a brinjal plant can last between eight months and two years, and a continuous harvest is obtained throughout the plant’s lifecycle.

“We get to a stage where production drops drastically or there’s eelworm in the soil, at which point we remove the plants.”

After many years of following a fertiliser programme prescribed by service providers, Kotzee now uses his own system.

“We found it’s better to be independent in this regard, so we get recommendations from several companies and then compare them.

“It’s important to understand what’s happening on the farm and not simply rely on advice from input suppliers. This means staying on the ball. By understanding how a fertiliser programme, irrigation and production cycles work, we’ve been able to better understand suppliers’ advice and know what’s right for our situation.”

Kotzee adds that brinjal, being a strong grower, is not overly dependent on nitrogen.

“You don’t have to pamper it to get it growing. Brinjals are actually quite low-maintenance when it comes to fertiliser. They prefer foliar feed, which includes phosphates and a few micro-elements. We think this is because they struggle to take up phosphates due to our compacted soil. We also use kelp products through the irrigation system to help strengthen the plants.”

Pest load is low compared with other crops, but Kotzee has to control thrips, white fly and Alternaria alternata, the most serious threat. This pathogen, which causes ageing in the plant, consists of two separate fungi, necessitating a combination of chemical groups for control. These are applied for two weeks, then alternated with other chemicals to prevent a build-up of resistance in the fungus.

To manage thrips and white fly, Kotzee mostly uses a compound such as acephate, but this must also be rotated with other chemicals to prevent resistance build-up. Due to the short withholding period, it can only be applied after harvest, before the next crop is planted.

He adds that they have started adjusting their pesticide programmes to encourage natural predators such as ladybirds and pollinators. They avoid harsh chemicals where possible, and apply pesticide at night, if conditions are suitable.

Nitrates and magnesium

An ongoing production challenge on the farm is high levels of magnesium and nitrates in the irrigation water drawn from the borehole. This causes soil compaction and problems with calcium uptake in the plants.

“We have deep loam soil, but the pH is very high at around 6,7. It should be about 5,” says Kotzee.

He spent a long time trying to get to the bottom of the soil problem before realising that the high magnesium and nitrate levels in the borehole water was the cause.

“We’re religious people,” he says.

“Often in life, we have questions that we can’t answer. At one stage, we were really wrestling with this problem of the crops that weren’t doing well and I was seeking answers all the time.

“One day, while walking around on the farm I suddenly felt drawn to a white patch of soil. It was caused by magnesium nitrates, and I suddenly understood that that was the problem. Minerals had built up in the soil over time as a result of the borehole water and we’re now in the process of trying to fix that.

“One method is to use lime, but lime also contains salt, so it’s only a small part of the solution. The other method is to build up the soil through micro-organisms and that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re doing a lot of research to get this balance right.”

He adds that AAL Boerdery has reached a turning point where they are focusing more

on soil health than plant health. “We could focus on plant health and get good harvests, but then what would be left of the soil if we didn’t look after it? We have to leave something for the next generation.”

Kotzee uses humates as part of the solution to rectify nitrate levels. Lime is added through fertigation at a volume of 5kg/ha/month.

“Lime has a calcium and a sulphur component. This rectifies the magnesium content in the soil as the calcium level needs to be increased to overcome the magnesium in order to release the potassium. The potassium in turn helps to ensure healthy fruit.”

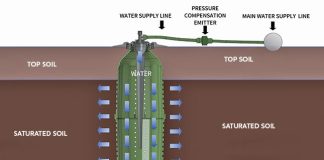

Compost is also added at 1kg/m along the dripper lines and the nutrients leach into the soil as it is irrigated. The brinjals receive 2ℓ of water per dripper per day. Soil moisture is monitored through tensiometers and irrigation adjusted where needed.

The brothers-in-law are trying to find a way of treating the water before it reaches the crops. “We only have boreholes on the farm; there are no rivers to draw from. The levels are dropping, which is of concern and prevents us from expanding,” says Kotzee.

Managing supply

While brinjals are a relatively easy crop to grow and manage, the market for them is limited, which prevents significant expansion of what would otherwise be the ideal vegetable crop.

This, says Kotzee, is in contrast to crops such as peppers and tomatoes, where demand allows for the production of huge volumes.

“Don’t think you can plant 5ha of brinjals and send it to market all at once. There’s a very fine balance between supply and demand, and this is what makes brinjals challenging.

“Demand also depends on where they’re marketed. We concentrate on fresh produce markets in Pretoria and Johannesburg, as the demand is better than in other parts of the country. Building good relationships at the market and delivering a consistent product is important to retain market share.”

He laments the lack of brinjal products. “Tiger Brands had a factory in Duiwelskloof that used to make a lot of chakalaka with brinjals and it was a good market for us. But they closed and moved to Groblersdal, and that has had an impact on the quantity we can produce.”

Prices are stable, on the other hand, which adds to the dependability of the crop.

Kotzee says they have faith in the future of the crop, and believe that demand will grow.

“Brinjals are known as the poor man’s meat, so they’re also good for the vegetarian market, which is growing.”

Email Theuns Kotzee at [email protected].