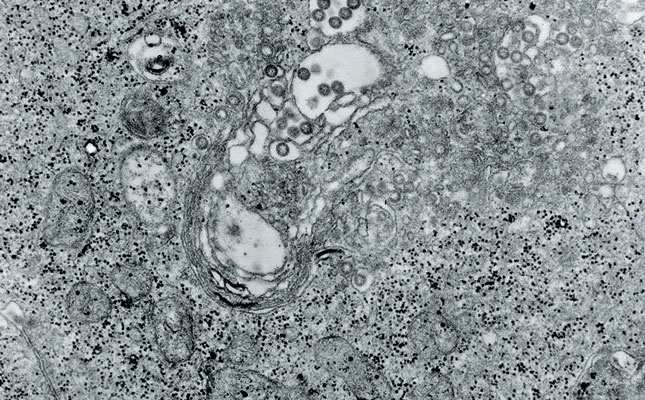

Rift Valley fever (RVF) is caused by a virus transmitted by mosquitoes during summer after heavy rainfall and persistent flooding. Thereafter, RVF spreads along river courses. Infected animals transmit the disease to others by means of aborted foetuses. RVF can also be spread by needles during vaccination.

RVF is a zoonosis: humans can contract it when handling sick animals or aborted foetuses, or performing post-mortem investigations. In fact, any person who works closely with animals, including an abattoir employee, can become infected.

Symptoms include fever, muscle pains and headaches that often last for up to a week. It can lead to loss of sight three weeks after infection.

Signs in sheep and goats

The RVF virus causes abortions in sheep and goats, leading to large-scale deaths in young lambs. Up to 95% can die within days.

The incubation phase is very short, and lambs can show signs of illness within one to three days of infection. Some die within just 12 hours. Newborn lambs are prime targets as their wool or hair is very short. Adult sheep show signs of weakness and sometimes bloody diarrhoea.

Bleeding from the nose also occurs.

Preventing infection

Two effective RVF vaccines are available for sheep and goats.

Live vaccine

This provides long-lasting protection after a single vaccination. But it cannot be used in pregnant animals as it may cause abortions. The vaccine also affects brain tissue.

If a pregnant ewe is vaccinated with it before the foetus is three months old, the vaccine will attack the undeveloped brain of the lamb and cause malformation.

The lambs and kids of vaccinated sheep and goats should be vaccinated at six months or at weaning but not before, or natural immunity will be destroyed.

Inactivated vaccine

This was developed for pregnant sheep and goats. Its disadvantage is that immunity lasts for only one year at most.

Source: Mohale, D: ‘Abortions and causes of death in newborn sheep and goats’ (ARC-Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute).