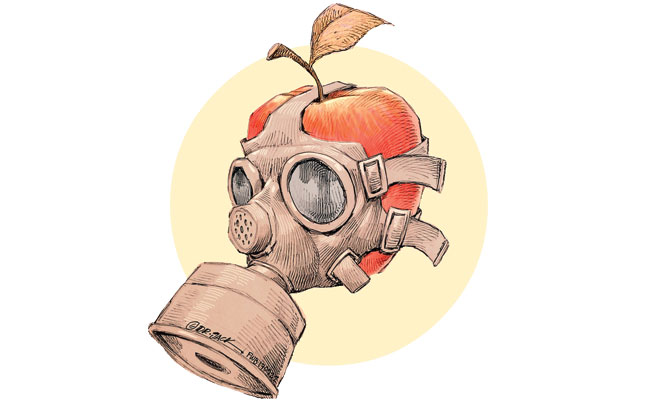

Photo: Dr Jack

South African retailers are increasingly aware that agrochemicals used in fresh produce production can pose a potential health risk to their customers.

This awareness largely stems from the ever-stricter regulations being imposed on agrochemical usage in Europe, such as maximum allowable residues of these chemicals on fresh produce, which are aimed at promoting human, animal and environmental safety.

Interestingly, trends that develop in Europe are likely to have an impact on farming practices in South Africa, especially where export crops are involved.

History of agrochemicals

Agrochemicals, in one form or another, have been used for hundreds of years around the world. In pre-World War II agriculture, the active ingredients in these fairly basic chemicals included salt, sulphur, calcium arsenate, arsenic, nicotine sulphate, and Bordeaux mixture (a mix of copper sulphate and slaked lime).

While some of these ingredients are relatively harmless and target only agricultural pests and diseases, others are deadly if handled inappropriately or ingested.

In her book, Silent spring, published in 1962, Rachel Carson highlighted the dangers that indiscriminate use of synthetic agrochemicals pose to human, animal and environmental health. Carson’s views created widespread awareness of this issue, and triggered the incremental development of ‘friendlier’ agrochemicals.

These included pyrethroids, insect growth regulators, and the Streptomyces-based avermectins.

Initially, the new agrochemicals met with resistance, with many producers preferring to continue using products they already knew. The turning point came in July 1985, when watermelons produced in California in the US became contaminated with highly toxic aldicarb pesticide, resulting in approximately 1 000 people accidentally being poisoned.

This was the largest ever case of food-based poisoning in the US, and led to the development of better methods of testing agrochemical residue levels on food products, as well as the implementation of further legislation to govern maximum allowable residue levels.

These US regulations started a trend that resulted in many countries adopting similar practices.

Testing for agrochemical residues on food and in the environment has subsequently been refined to the point where parts per billion can now be measured.

There has also been a significant increase in public awareness of food safety issues, which has led to the establishment of pressure groups to lobby governments to implement policies aimed at enhancing food and environmental safety.

The role of digital media

Social media and the Internet have been mixed blessings in terms of agrochemical residues, as information can be accurate and informative, or wildly inaccurate.

The latter tends to overshadow the former, unfortunately, as many people gravitate towards sensational news and fail to check for accuracy. They are quick to believe that the majority of modern farmers indiscriminately use toxic agrochemicals as part of their food production practices.

On the other hand, there have been many cases where agrochemicals were abused, and this has resulted in valid concerns about chemical residues on food products.

Much of the world, including South Africa, has reached a middle ground between the use of synthetic agrochemicals and integrated pest management (IPM) tools, such as biological agents, to control agricultural pests and diseases.

IPM is still in its infancy for many crops, but is rapidly growing in popularity, and increased implementation will lead to a significant reduction in the need for, and use of, agrochemicals.

This is especially important because governments around the world, especially in Europe, are increasingly issuing directives that strictly control, or even outright ban, active ingredients considered undesirable or potentially harmful to humans, animals and the environment.

Increasing restrictions

In 1991, the European Commission issued Directive 91/414/EEC, slashing the number of active ingredients registered for agrochemicals in Europe from about 1 000 to around 230. In the decades since then, South Africa too has seen a noticeable decrease in the number of active ingredients registered.

The European Commission is currently reviewing a further 40 of these ingredients, and South Africa is likely to follow suit eventually.

Many major retail chains in the EU support the European Commission’s ban on certain active ingredients in agrochemicals, and expect that residues on the produce they procure not to exceed 30% of the European Commission-stipulated maximum allowable limits.

The downside

These measures place tremendous pressure on food producers worldwide and are likely to cause harm in the long term.

For example, to achieve the stringent maximum allowable limits on citrus set by retailers, growers may have to apply post-harvest fungicides at below recommended levels.

The downside of this is that the fungal diseases targeted by these fungicides are likely to eventually become resistant. In turn, this could lead to post-harvest quality problems in years to come when no effective active ingredients remain.

In South Africa, the public increasingly engages major retail chains on the ethical production of safe food. I make it a point to respond, on behalf of Woolworths, to any concerns raised, and, where necessary, investigate and address genuine problems with our produce growers.

An added challenge is products that have not been registered in South Africa, but are sold here as agrochemicals or sanitising soaps.

While farmers may use these with good intentions, some of the products result in undesirable chemical residues on produce destined for consumers.

I, therefore, urge farmers to ensure that they use only registered products and only for the registered use intended. At Woolworths, we are happy to advise them on the maximum allowable agrochemical residue levels on the fresh produce we procure from them.

Woolworths is also working with its produce suppliers to implement integrated pest management practices. We strongly encourage them to avoid using pesticides and other agrochemicals unless absolutely necessary.

If they have to use an agrochemical, they should ensure that it is the correct one and it is applied correctly.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Phone Tom Murray on 021 407 3024, or email [email protected].

This presentation was made at the Intensive Growers’ Association’s

2017 Spring-Summer Symposium, held in Durban on 20 July.