Photo: Dr Jack

As the planet’s human population grows, the area of arable land available to feed and clothe each person continually declines. It is anticipated that this figure will be approximately 0,15ha/ person by 2050, compared with 0,3ha/person in 1980.

So the global agriculture sector, including its livestock industry, is facing the massive challenge of having to significantly improve its productivity to adequately feed everybody, while using fewer resources.

Animal rights activists pose a major threat to the international livestock industry’s ability to improve its productivity into the future. These activists have surprisingly large financial resources and they influence policymakers and the general public.

They are able to get consumers to take a closer look at and to question the methods used to produce animal products.

It’s good that consumers want to know more about how their food and fibre are produced.

It’s not good if the information they are being provided with comes only from these activists, who have their own particular agendas.

The world’s livestock production sector must also share information about its systems so that consumers are given a balanced perspective with which to make informed decisions.

The international dairy industry has been one such target of animal rights activists, who claim that commercial milk production is not environmentally friendly. Yet substantial bodies of research show that every dairy production system, whether extensive or intensive, can and should be environmentally sustainable.

Achieving sustainability

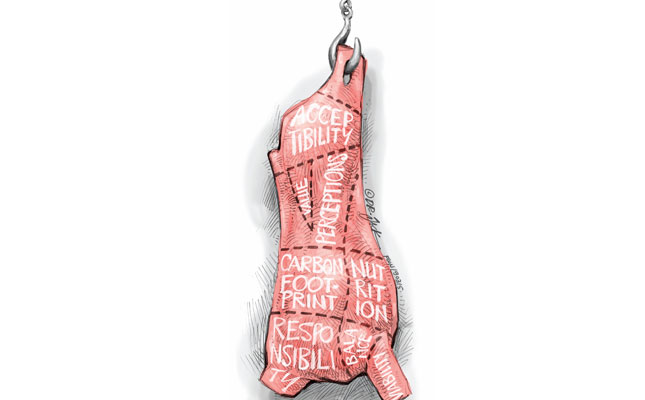

Three components are essential for a livestock operation to achieve sustainability. Most important is meeting the social acceptability component of sustainability.

This requires a livestock operation, and the value chain that it is part of, to make every effort to ensure that consumers still want its products. Without a strong market for these products, the entire meat or milk value chain would cease to exist.

The second component of sustainability is economic viability. Every livestock enterprise must make a profit, or it will ultimately go out of business.

The third component is environmental responsibility. As a livestock industry, we know that we have to care for the land, air, water, animals and environment. But we need to make the policymaker, processer, retailer and consumer realise that we do care.

These three components combine in the One Health approach, which recognises the health of the animals, the people and the environment.

All three are required for sustainability in food production and consumption, yet consumers don’t always appreciate the need to balance them.

A survey of 5 000 people across Europe found that people generally tended to prioritise environmental aspects such as sourcing only local and seasonal food, and contributing towards healthy air and water resources. To a lesser degree, they prioritised food cost, food safety and animal welfare.

So agriculture’s carbon footprint and greenhouse gas emissions have, to some extent, become the proxy for negative environmental impacts in general.

If we compare food products, for example meat, value-added dairy, grains, and fruits and vegetables, we find that meat production generates 6,2kg of carbon (C) per kilogram of meat products, followed by value-added dairy at 3,6kg of C/kg of dairy products; grains at 3,2kg of C/kg; fruit and vegetables at 1,9kg of C/ kg; and non-valued-added milk at 1,2kg of C/kg.

Fighting the good fight

If food consumers are primarily concerned about reducing their carbon footprint via their diet, then livestock production does fairly well in this respect.

Yet the global livestock industry continues to face the challenge of being labelled in many media as having a high negative environmental impact. Whatever the foods that people eat, there will always be some level of impact on the environment.

Posing a survival threat to the world’s livestock production industry are international campaigns such as Meat-free Mondays.

These and other anti-animal products campaigns are gaining momentum globally because the people who run them regularly use emotive language and images that the average animal products consumer finds upsetting.

But if objective science rather than subjective emotion is brought into the debate, a different picture emerges. For example, scientifically generated data shows that the total carbon emissions from German livestock production make up only about 4,8% of that country’s total national greenhouse gas emissions.

This means that 95,2% of Germany’s carbon emissions are generated by everything else, including transport, conference centres, hotels and other carbon emitters that anti-animal products campaigners utilise.

This data means the perception that going meat-free for one day every week would make a huge impact on reducing carbon emissions is simply untrue. Even if it were possible to get every single person in Germany to go meat-free for one day a week, this would reduce Germany’s total carbon emissions by a mere 0,7%.

I’m not saying that the world’s animal production sector should not be doing everything that it can to cut farm emissions and minimise its environmental impact, because these are positive activities. But people need to make wholesale changes across their lives instead of simply demonising meat or dairy.

There are a number of ways that the global animal production sector can make meaningful contributions to environmental sustainability.

One of the most important is to improve the productivity and efficiency of meat animals and dairy cows, while maintaining health and welfare, to reduce the level of land, water, fuel and carbon emissions for every unit of meat or dairy product produced. And this can be achieved at lower economic cost to the farmer.

Nutrient density

Livestock farmers should also educate consumers about the benefits of their products.

For example, many consumers are unlikely to be aware of the scientific fact that milk has a nutrient density, without energy, of 53,8% of its total volume, while the soya and oat drinks that are consumed as alternatives to milk have nutrient densities, without energy, of 7,6% and 1,5% respectively.

Milk production generates 99g of carbon dioxide (CO2) per 1g of milk, while soya and oat drinks generate 30g of CO2 and 21g of CO2 per 1g respectively. To achieve the equivalent nutrient intake, without energy, provided by 100g of milk, consumers would need to drink 707g of soya juice or 3 586g of oat juice.

Producing 100g of milk would generate 9 900g of CO2, while producing 707g of soya juice would generate 21 210g of CO2 and producing 3 586g of oat milk would generate 75 306g of CO2.

Anti-animal products campaigners and food consumers should start including nutrient density as a key factor when assessing the carbon footprint of food products.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

Email Dr Jude Capper at [email protected], or visit bovidiva.com. This is an excerpt from a presentation given by Capper at EuroTier 2018 held in Hannover, Germany, in November.

Farmer’s Weekly journalist Lloyd Phillips was sponsored by the German Agricultural Society to attend EuroTier 2018.