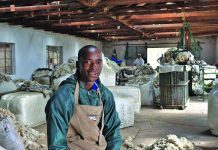

Photo: Sabrina Dean

Mariaan Grobler loves her goats. She also loves the opportunities presented by a commercial goat farming operation.

“You can make money from these animals,” she says.

Grobler and her husband, Cobus, live on the farm Verona just outside Dewetsdorp in the Free State, where she currently runs a herd of about 120 commercial Boer goat ewes on 10ha.

READ Getting started with dairy goats: practical tips from a farmer

Grobler has been farming goats for years, but has only recently begun to commercialise and expand her operation, aligning it to her ultimate goal of eventually going into stud production.

Her main aim currently is to sell the goats for their meat value. She produces them not only for the consumer’s plate, but for the lucrative cultural and traditional market, where goats for ritual sacrifice are always in demand.

Grobler also focuses on improving the genetic quality of her production herd, selecting according to the guidelines set out by the South African Boer Goat Breeders’ Society.

READ Strict selection the key to Boer goat meat production

In 2015 she decided to start introducing premium genetics into her herd and collaborated with Kobus Lötter of Doornpoort Genetics.

“He came to class my flock and that was also when I bought my first Doornpoort ram,” she says.

Grobler had been slowly and steadily increasing her flock or years, but the quality of the animals was not as high as it could be. She began by culling all ewes that failed to meet the breed standard, reducing her flock from more than 160 ewes to fewer than a hundred.

“A poor quality ewe eats just as much as a good one,” she says.

Having whittled down the flock to the best ewes, Grobler is now striving to maintain an ideal kidding percentage of 180%. “I select for twins or triplets,” she explains.

Careful selection

Ewes must kid every year, be good mothers and produce enough milk to raise all their offspring. Grobler also looks for a strong head with a feminine expression and a slightly bowed nose.

READ A sturdy breed: some Toggenburg basics

A breeding ram must have good length, depth and balance in the body, as well as a long rump, as such goats tend to carry more meat. Using a quality ram is non-negotiable, as this is the only way to enable genetic progress.

“A good ram can’t be replaced by anything else,” stresses Grobler.

She uses one ram to between 20 and 30 ewes, which she synchronises before breeding to make the kidding season more manageable.

A ram is kept with a flock of ewes for six to eight weeks. The ewes are then scanned and separated for appropriate feeding and care depending on how many kids each is carrying.

Those bearing triplets receive priority care, and first-time ewes also get a helping hand.

Because the groups of ewes are synchronised for breeding, ewes often kid simultaneously in a single night, so Grobler ensures that she is on hand during this time. In fact, she says that all her work revolves around this period, adding: “Poor kidding can affect your entire business.”

She considers any marketable goat valuable, and during tough economic times does not reduce the feed for ewes carrying single kids.

Lambing

Goats are normally seasonal breeding animals, with their peak heat periods in either March/April/May or September/October/November, explains Grobler.

Her goats are not bred seasonally, but according to a nine-month timeline: five months’ gestation, three months until weaning, and another month for recovery. This enables Grobler to have marketable goats all year except for November, December and January, when the weather is too hot.

“The goats get dehydrated and there are too many flies,” she says, adding that she also finds it more difficult to get the animals to gain weight in the heat.

She tries to limit stress, including handling and feeding stress, before and during kidding.

“Feeding properly up to kidding is essential,” she adds.

It’s also critical that a maiden ewe be at least at 80% of her mature weight when bred for the first time, otherwise her first kid may be handicapped and she is likely to remain small and produce small kids thereafter.

“You reduce the potential of that ewe for the rest of her breeding life,” says Grobler.

She also gives ewes a second chance if they don’t fall pregnant the first time around.

Intensive management

Grobler believes an intensive goat system is something any livestock farmer can cope with, adding that it is possible to start out without necessarily having to invest in expensive infrastructure.

However, good management is essential, she stresses, as high numbers of livestock are concentrated in a small area. Amongst other factors, this leads to a greater concentration of manure, which can add to the pest burden.

Even a hardy and resistant animal like a goat can become susceptible to ailments in a poorly managed intensive system.

Grobler currently uses about 10ha of the farm for her goat operation, and this area includes grazing and kidding camps.

In addition to having access to daytime grazing, the goats are fed lucerne, which is always readily available in the area, as well as a balanced protein concentrate mixed with crushed maize.

“They need this for milk production and growth of the kids,” explains Grobler.

Kids receive creep feed from two weeks of age until weaning.

Grobler doses against tapeworm regularly and administers only those vaccinations deemed necessary for goats in her area. All kids receive a Multivax P+ vaccine at six weeks, followed by another at 12 weeks. Adults receive a booster shot once a year.

Every animal is tagged at birth and Grobler records its number, its date of birth, and the name or number of its sire and dam.

Kids are monitored closely to ensure they receive sufficient nutrition and are supplemented if necessary. “You can pick up a kid and feel if it is getting enough milk,” says Grobler.

Weaning and marketing

Boer goat farming is economically viable, she says, but a farmer needs at least 100 ewes to provide the necessary economy of scale.

In addition, the focus in a commercial operation must be on delivering “maximum meat at minimum weight”. This means that it is best to market goats as soon as possible after weaning.

At a weaning age of around three months, a young goat will weigh about 20kg. To get it to a mature size of about 45kg, it has to be fed for eight months.

“For most farmers, it’s not profitable to feed it to full size,” says Grobler.

Buyers who purchase goats for traditional and cultural purposes tend to have a very specific idea of the type of animal they are looking for.

They will then pay a premium for their chosen animal, which does not necessarily need to be a mature goat.

What is more, there’s a market most of the year as goats are purchased not only for traditional festivals or religious days, but also to mark important occasions such as births or deaths.

For a commercial producer like Grobler, it is far easier to generate cash flow by loading her stock onto a trailer and driving the goats to a sale attended by buyers from KwaZulu-Natal than to explore options on the consumer retail market.

“Goats are more expensive than sheep and that’s because we can’t keep up with demand,” she says.

She adds that there is considerable opportunity for emerging goat farmers to enter the commercial arena, but they are in desperate need of knowledge and good-quality genetics.

She tries to assist by sometimes entering into arrangements with individuals, where she swops a young, well-bred ram for an adult goat of lesser genetic quality that she can still sell for profit.

The future

Grobler hopes to improve the grazing and fodder crops in her camps or introduce seasonal additives such as radishes.

Her long-term goal is more ambitious, but is certainly the next logical step in her tightly run operation: to improve the quality of her flock to the point where she can produce stud animals.

Phone Mariaan Grobler on 079 476 8675 or email her at [email protected].