How important is the SKA site bid outcome for South Africa? What does it mean for the country?

This is a very significant moment for South Africa, and Africa as a whole. It is also an important milestone in the international SKA project – the overall winner here is global science. For South Africa and our African partner countries this represents a new era, where Africa is seen as a science destination and takes its place as an equal peer in global science.

Prof Justin Jonas. Photo by: Loretta Steyn

How will the SKA be split between Africa and Australia? Is this feasible, given the distance between the two continents?

The SKA consists of two quite distinct components – one working at low frequencies and one working at mid frequencies. The two components use very different antennae technologies and operate independently. For this reason it’s quite easy to separate the SKA into these two components, and build them on separate sites. Even if the SKA had been allocated to one country, the two components would have been separated by quite a large distance.

How will components of the SKA be split across both continents?

South Africa, together with eight African partner countries (Namibia, Botswana, Zambia, Mozambique, Kenya, Ghana, Madagascar and Mauritius), has been allocated the Phase 2 mid-frequency dish array, and Australia has been allocated the Phase 2 low-frequency aperture array. The higher elevation of the South African site makes it more suitable for observing at the mid frequencies.

What is the budget for the SKA? How much will South Africa be contributing towards it, and how will project financing be divided among the participating countries?

Innovation, Industry, Science and Research; Canada’s National Research Council; China’s National Astronomical Observatories; the Chinese Academy of Sciences; Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics; New Zealand’s Ministry of Economic Development; South Africa’s National Research Foundation; the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research; and the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council.

The SKA will be built in the Karoo region. What is the exact location and size of the site and what makes it ideal?

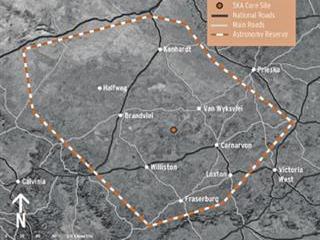

The SKA will be located on two farms purchased by the South African government in the area between Brandvlei, Carnarvon and Williston in the Karoo. The total area amounts to about 14 000ha. It’s a ‘radio quiet’ region, being in a remote area with sparse population and no economic activity other than low density farming. It’s also a dry, high plateau providing good atmospheric and tropospheric conditions for mid-frequency observations. Although it’s remote, it’s well-serviced with basic infrastructure such as utility grid power and roads.

Because of the fact that the site has to remain a ‘radio quiet region’, there has been some concern from farmers in the Brandvlei, Carnavon and Williston regions about continued access to cellphone reception. How will farmers and residents be affected in this regard and what interaction have you had with communities in the area to explain the impact the SKA might have on them?

Yes, a small number of farmers and their employees will be affected by the regulations in terms of the Astronomy Geographic Advantage Act of 2007, which will regulate transmissions in the area which might interfere with the MeerKAT or the SKA. For example, the cellphone tower in Brandvlei has been modified to restrict signals that are directed to our site and this has affected some farmers. But the South African SKA project and the Department of Science and Technology are working with Agri Northern Cape and the affected farmers to implement alternative solutions for services which might be lost, including TV, emergency communications, trunked telecommunications and even internet connections.

Agri Northern Cape supports the South African SKA project and has been involved in the project since May 2010. A forum was created to look after the interests of farmers who are affected by the project. In addition, stakeholder meetings are being held on a regular basis where all interested parties are involved. This includes organised agriculture, MTN, Vodacom, SKA and the Department of Science and Technology. Telkom has now also joined in the forum’s activities.

There have been some reports that the SKA project is likely to clash with Shell’s plans to use hydraulic fracturing to explore for shale gas in the Karoo. Is this true?

The Astronomy Geographic Advantage Act provides protection for all astronomy activities within designated areas within the Northern Cape, and it gives the science ministry a mandate to cut down trees, re-route air flights, silence radio signals and prohibit anything that harms astronomy in the region. SKA South Africa does have a representative on the working group on fracking and we have indicated our requirements, including those stipulations set out in the act.

However, this does not automatically mean that there can be no fracking in the region. We have given specified guidelines as to how fracking can be done in order to cause no interference with the SKA project. If Shell, or any company wishing to explore for shale gas in the Karoo region, can work within those constraints we have no further grounds for stopping them.

What kind of impact will the SKA have on the development of science and technology in Africa?

The SKA has already had an impact through the MeerKAT project and the human capital development project managed by the SKA South Africa project office. The MeerKAT has provided African academia and industry with challenges that have improved their competitiveness, and the human capital programme has increased the numbers of students taking degrees up to the PhD level in physics, mathematics and engineering. Being much larger, the SKA will take this to the next level.

Construction of the telescope is set to begin in 2016. What preparations need to be made in the next four years and by when will the telescope be operational?

The next step for the SKA is a detailed design and pre-construction phase (2013-2015) followed by the construction of SKA Phase 1 – making up about 10% of the total instrument. Scientists should be able to use SKA Phase 1 for research by 2020. By that time, construction on SKA Phase 2 should be underway (2018-2023) with full science operations commencing by 2024.

What will the SKA look like and what will it look for?

“The key science programmes are all transformational in that they will provide answers to fundamental questions in physics, astronomy and cosmology,” says Prof Jonas. Scientists expect that the Square Kilometre Array telescope will make new discoveries about the universe that we have not imagined yet.

South Africa is currently building the Karoo Array Telescope, or MeerKAT, a mid-frequency ‘pathfinder’ or demonstrator radio telescope, alongside the proposed SKA core site. The first seven dishes (some of them seen here) of the local precursor instrument were completed by December 2010. The MeerKAT array will be the largest and most sensitive radio telescope in the southern hemisphere until the SKA is completed around 2024. Photo by: Dr Nadeem Oozeer

The SKA will consist of thousands of different types of antennae spread out over large areas. Some will be shaped like dishes, while others will look like flat tiles and TV antennas.” The SKA’s science objectives and artist’s impressions of what

the dishes will look like can be found by visiting www.skatelescope.org

Contact Prof Justin Jonas on 046 603 7361 or at [email protected]