A successful black professional was recently quoted as saying something to the effect that “people don’t seem to understand: nothing that can happen is worse than apartheid”. On face value, this makes sense. However, one should be careful of taking that argument too far, as it implies that the wrongs of the past should be rectified immediately, whatever the consequences.

When they look back on land reform since 1994, many commercial farmers see an underlying message: the land must be redistributed even if it means the breakdown of a well-established agricultural industry. Only then, once certain goals have been reached, can the focus switch to rebuilding. That makes for a paralysing, complex mix of redress, restitution and revenge for farmers to worry about.

Yet, despite the many hurdles, commercial farming has survived, and even excelled in certain areas. Yes, commercial farmer numbers have tumbled (and will continue to do so), but this has been more as a result of natural attrition, led by global economic realities and creeping old age than government policies.

READ: Land reform success for Western Cape fruit farmer

Many white commercial farmers, who still own and manage most of the land outside the former homelands, experience the land reform debate as a psychological war, with politicians varying the attack in typical iron-fist/silk-glove style, making it hard for farmers to distinguish between bluff and genuine support.

Does government really want to get rid of them and take their farms, or is it mostly hot air to please rural voters? This game has, in 20 years, done little more than move the land reform discussion from one in which one-third of commercial farming land was to have been quickly transferred, to the current ideas of a land cap and equity for farm workers.

During all this time, much money has been spent, a lot of it fruitlessly, on emerging farmer projects, land claims and counter-claims. Reasons for the general failure of the process are well known, but one mistake that is hardly mentioned is the original notion that one could, with a snap of the fingers and without doing great socio-economic damage, change land-use patterns that had evolved over centuries.

Black people had been kept out of mainstream commercial agriculture for very long. Unfortunately, when their turn came to bat, government had little institutional memory or practical knowledge of modern-day agriculture in South Africa. The result was that too much faith was placed on revolutionary politics and foreign consultants with no idea of local conditions and how to approach them. It was not politically correct to speak to experienced white commercial farmers or their technical advisers, let alone listen to them.

Farmers’ response

On the other hand, it has taken commercial farmers far too long to decide on what role to play in the process. The emphasis was more on shooting down projects and evading issues than tackling the challenges head on and seeking win-win schemes. The bigger farmers are at last making themselves heard, but valuable time has been lost. And, bearing in mind that time is money, the losses will probably never be fully recovered.

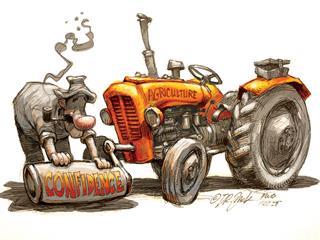

More frightening is that, in terms of agricultural economics, the margin for error is tighter than ever. The sector is unlikely to be able to absorb the high cost of failures much longer. For growth, the agricultural sector, like every other, requires confidence in the future. Agriculture needs an operating climate in which local entrepreneurial farmers are prepared to risk investment in land, improvements, labour and production.

This will enable them to generate money that could allow effective land reform to take place, independently of state control. Then, no laws will be needed to keep outsiders from owning land and there need be no debate about the pros and cons of mega-farms, food security, or rural decay and ensuing poverty.

Confidence is the cheapest catalyst for agricultural development while falling land prices, driven by fear and uncertainty, are the surest route to stagnation.Commercial farmers, aspiring new farmers and government should sit down again to map out a new road based on the economic realities of the future rather than on the follies of the past.

Email Roelof Bezuidenhout at [email protected].