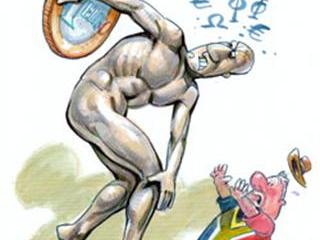

The current turmoil in global markets, due to uncertainties surrounding Greece’s economic survival, can play out in two different ways, and will affect SA farmers’ pockets. It all began as a project in the 1950s to eradicate the possibility of European countries ever engaging in a disruptive world war again. The project, known as the European Union (back then it was called the European Economic Community), culminated in the early 2000s with the introduction of a single currency, the euro.

Some 17 countries, called the Eurozone, use this currency and Greece is one of them. Not all the member countries of the EU, the UK for example, use the euro. To be part of the Eurozone, countries have to adhere to strict government spending rules. A country’s debt as percentage of its annual economic output shouldn’t exceed 60%, and the financing gap between a government’s spending and its taxes received as percentage of economic output shouldn’t exceed 3%.

When Greece was allowed to join the Eurozone in the early 2000s, there was doubt about the integrity of the country’s statistics – in layman’s terms. And Greece was allowed to join the Eurozone on the basis of these figures and, worse, it was allowed to stay in this club. The government suddenly had access to cheap euro-denominated debt and a debt party kicked off.

This jollification ended in 2008 and the country still hasn’t emerged from its debt hangover. Greece will hold a second election in as many months on 17 June. The new government will have to steer the fragile and leaking economic ship between Scylla and Charybdis.

Scylla

The first option is for Greece to leave the Eurozone and adopt its own currency. This, it’s speculated, will lead to short-term hardship, which may include fuel and hard cash shortages, the evaporation of savings, food shortages, wage destruction and even social unrest. The global financial markets, which eventually determine the value of the euro, would most probably react positively towards the euro and we should see an appreciation in the value of the euro.

As the rand’s value (against other currencies) moves closely with the euro, it will most probably appreciate in tandem. A stronger rand could result in a lower fuel price, easing the pressure on South African farmers’ profitability. An exit by Greece will most likely boost investor and consumer sentiment in the EU and lead to stronger economic growth. As more than a third of SA’s agricultural products find their way to the EU, according to the National Agricultural Marketing Council, this will boost the off-take of SA produce, including wool, fruit, vegetables and mohair.

Charybdis

The second option, and the most unlikely one, is that Greece will stay in the Eurozone, tidy up its tax collection system and fight chronic tax evasion. Financial markets will most likely punish the euro by selling it off and buying dollars, which will be perceived as safer. This will cause the euro to depreciate, with the rand following suit. More rands will be needed to buy a dollar.

Local fuel prices will be under pressure as more rands are needed to buy the same dollar amount of oil. Higher import prices will not be limited to oil. Agricultural machinery will also see price hikes, as will imported chemicals, used to produce animal medicines, pesticides and herbicides.

Agricultural exports to other world regions, like the rest of Africa (where currencies tend to follow the US dollar, but are historically linked to the euro), the US, China (whose currency is unofficially pegged to the US dollar) and the Middle East, will do well in money terms. Exporters will receive more rand for the same volume of exports.

It is, however, in this scenario where a zero-sum game is possible. In a perfect world, the amount by which input costs, mainly fuel, fertiliser and animal medicine prices rise, ought, with no middlemen, to be the same as the increased revenue farmers will receive for their produce. This is highly unlikely, though, and farmers may feel some cost pressure despite higher receipts for their produce.

A precedent

If Greece exits the Eurozone, much of the current global uncertainty will disappear. What is happening in the country now is unprecedented and will set an example for the future. Investors – who ultimately dictate the rise and fall of economies – will have an example to look to if similarly highly indebted Portugal, Ireland and possibly Italy and Spain also exit the Eurozone.

This would most probably soften the blow to the value of fringe currencies such as the rand and, to an extent, the blow to farmers’ bottom lines.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.