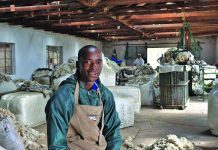

Photo: Mike Burgess

According to Ross Rayner, the value of his indigenous livestock lies in their ability to produce efficiently and effectively under often unpredictable natural conditions with minimal input costs.

What’s more, he stresses, indigenous breeds not only offer emerging farmers hardy livestock, but give them the ability to access potentially lucrative niche markets.

READ Indigenous species: let’s widen the net for aquaculture

“Indigenous livestock is the key to the successful entry of emerging farmers into the agriculture sector, while offering great potential for the cost-effective production of grass-fed beef and mutton,” he says.

In 2007, Rayner started farming Nguni cattle and Indigenous Veld Goats (IVGs) on the family farm, Walkersvale, near Adelaide in the Eastern Cape.

Although his IVGs, which were dominated by the Xhosa Lob Ear and Mbuzi ecotypes, were hardy and very fertile, keeping them on the right side of the boundary fence became a major management headache.

About six years ago he therefore began investigating the possibility of introducing indigenous sheep, which he believed would not creep through fences as easily as the IVGs.

By 2013, he had found out about indigenous livestock enthusiasts Scott and Christopher Atherstone near Tzaneen in Limpopo, who farmed both IVGs and Pedi sheep.

Then in December 2013, Rayner and fellow Eastern Cape indigenous livestock farmer Lionel Whittal made their way up to Tzaneen.

“I thought I would like to learn more about these sheep,” says Rayner. “So we put some diesel in a bakkie and set out for Limpopo.”

READ Basic goat health management: all you need to know

The Atherstone brothers escorted their Eastern Cape guests through the former communal homelands in Limpopo in search of indigenous sheep and goats before introducing them to a number of commercial farmers who specialised in indigenous small stock.

To Rayner’s surprise, he found that a study group had been established in 2009 to promote the value of the Pedi and the Super Pedi, or Bosvelder.

The aim of developing the currently unregistered Bosvelder has been an attempt to improve the carcass qualities of the Pedi, but retain its legendary adaptability, fertility and immunity to tick-borne diseases.

In the end, Rayner left Limpopo with five Pedi ewes and two rams to begin building his first indigenous flock of sheep in the Mankazana Valley.

By 2014, he had introduced another 10 indigenous Nguni or Zulu-type ewes (sourced in KwaZulu- Natal), three Meatmaster ewes and a ram (from the Karoo) to his flock. In the same year, he sold all his IVGs and committed himself to his indigenous sheep.

Towards the Bosvelder

Rayner is convinced a Bosvelder-type sheep is the best small-stock option for Walkersvale.

“The Pedi is the secret. But I decided to breed a Bosvelder type with a slightly better carcass that’s still easy to manage on the veld,” he says.

The current Bosvelder flock sire, Eastwood, is the product of one of the in-lamb ewes Rayner originally purchased in Limpopo mated to a Meatmaster ram. Eastwood was born on Walkersvale.

Currently, Eastwood is run throughout the year with the ewes, which achieve a lambing rate of between 110% and 120% on the veld. Most adult ewes produce two lambs a year, and although some maiden ewes lamb with ease at one year, Rayner prefers them to lamb at about 18 months.

However, it is the longevity and mothering abilities of the ewes that are particularly impressive, he says.

READ Indigenous veld goats: A family’s profitable passion

“Some sheep have lambs, but they have no teeth left in their heads. Lambs are always quickly on their feet, following their protective mothers in the veld.”

The sheep are dosed for worms in spring and again in summer. Screw worm has been an occasional problem in the deep folds of the tails of mature Pedi wethers, and this is treated when necessary.

Despite roaming on veld with heavy tick loads, the sheep (dipped on the rare occasion) have shown admirable immunity to tick-borne diseases such as heartwater.

“Through the years I can count the cases I have had on one hand and they are normally young sheep,” says Rayner. “And most of those pulled through.”

The only supplementation the sheep receive on the veld is a protein lick towards the end of winter when it becomes exceptionally dry.

Ngunis

Rayner also started farming Nguni cattle on Walkersvale in 2007. Foundation animals were acquired from Stephen Cockcroft (Adelaide), the late Chris Bush of Molweni Private Game Reserve (Adelaide) and Jacques Steenkamp (Humansdorp).

Genetics were also purchased at the annual Eastern Cape Nguni Club Sale in Queenstown.

The Rayner Ngunis have proved to be excellent producers on the veld where heartwater, redwater and gallsickness are common. This was particularly evident in the recent drought years when their ability to browse proved critical.

“When there was no grass left, they would climb the steepest parts of the farm to reach the spekboom [Portulacaria afra],” Rayner says.

“If the cattle hadn’t eaten bush [during the drought] they would have been gone.”

What’s more, despite the threat of tick-borne diseases, the herd is dipped only when tick loads are visibly heavy. Incredibly, Rayner says, his cattle are not subjected to any inoculation or dosing regimes, although he has treated them when unique risks such as Rift Valley fever have surfaced.

Cattle receive a phosphate lick in summer and a maintenance lick halfway through winter.

A disadvantage of the purebred Nguni has been their smaller weaners, which are unpopular with feedlotters. Although Rayner knows that one solution would be to grow out Nguni oxen, lack of space on Walkersvale has made this impossible.

He thus recently began a terminal crossbreeding programme with bulls sourced from the nearby Frontier Boran stud. The Nguni x Boran weaners have been very impressive, he says.

“If you’re terminal-crossing, there’s no better dam line than a Nguni cow,” he says.

“The conformation on the [Boran]weaners [which average about 210kg at eight months] is a lot better [than the Nguni].”

READ A unique farm-to-fork Nguni operation

Bulls are kept in the herd all year round, with most cows calving in October and November.

Heifers are preferably mated at two years and some cows are still producing at 13 years old.

In future, Nguni bulls will be used in the herd to produce Nguni replacement heifers for the crossbreeding programme.

Phone Ross Rayner on 071 777 9927.