Photo: Prof PG Goussard

Over the 2021/22 season, wet spring and summer conditions resulted in an explosion of powdery mildew infestations on wine grape farms in various regions in the Western and Southern Cape.

Not only did the fungal disease negatively affect yields, it also drove up production costs, as farmers were forced to use more fungicides than usual in an attempt to combat the disease.

In addition, before harvesting could take place, they also had to send workers into the vineyards to remove infected berries by hand, or risk them having an undesirable effect on wine quality.

De Wet du Toit, a crop protection specialist at Winfield United South Africa, told farmers at a Winetech Vinpro information day held in May in Rawsonville, Western Cape, that early action was key to the successful management of powdery mildew.

“Instead of waiting for signs of powdery mildew to appear before taking action, it’s better to follow a spraying programme from early on in the season to prevent the disease from spiralling out of control. You can’t destroy powdery mildew, so prevention is much cheaper and more effective than trying to eradicate the disease,” he explained.

The foe

While there is an absence of physical signs when plants first become infected with powdery mildew, farmers should know that poor management and high disease pressure in one season are an indication of more problems to come in the next.

Du Toit said the fungus overwintered in dormant buds, which released spores after bud break. These spores were carried on the wind to neighbouring vines, where they germinated to form new infections within five to 10 days. Once a vine had become infected, it took between seven and 28 days, depending on climatic conditions, for the characteristic white powdery stains to form on the leaves.

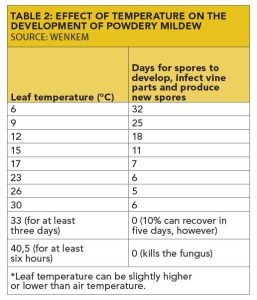

He added that powdery mildew usually developed at temperatures of between 20°C and 27°C (see Table 2), with relative humidity of more than 75%. The fungus could be destroyed when exposed to temperatures above 40°C for at least six hours. However, such temperatures were rare in vine canopies, especially those of vigorous growers with a lot of foliage.

Other contributing factors to the development of powdery mildew include periods of reduced ultraviolet radiation, such as when the days are overcast or when overshadowing occurs in leaf canopies; as well as a lack of air movement through canopies, especially thicker ones.

The spores don’t require free water to germinate, so rainy conditions aren’t a requisite for disease development.

“Some tunnel farmers use irrigation to wash powdery mildew from their vegetables, but this won’t work outside, as the fungus might be present at multiple developmental stages in the vineyard,” Du Toit said.

The fungus mainly attacks the green parts of the plant. Once the berries have reached a Brix value of 12 to 13, they are no longer susceptible; however, the leaves and stems remain prone to infection.

Du Toit said the wine grape varieties that were most susceptible to the disease were Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, Sémillon, Pinotage, Muscadel, Hanepoot and Ruby Cabernet.

The weapons

Speaking at the information day, Gustav Rademeyer, crop protection specialist at Wenkem, said farmers should put proper plans in place for their spray programmes before the start of the season. Depending on disease pressure and farmers’ access to implements, applications should be made every second or third week.

“If you farm in a high-risk area, a two-week programme is recommended, while a three-week programme will suffice in a low-risk area,” explained Rademeyer.

“Spraying every third week will require higher dosages and is riskier than applying fungicides every other week. Some farmers can get away with it, but that is not the case if you farm in a region where environmental conditions are conducive to the development of powdery mildew,” he added.

Rademeyer said that mistakes made in a powdery mildew spraying programme could be corrected by applying dusting sulphur between the flowering stage and when the grape berries have reached pea size, but added that the weather had to be taken into account when doing so.

“In windy areas, such as Worcester and Rawsonville, conditions aren’t always favourable for applying dusting sulphur.”

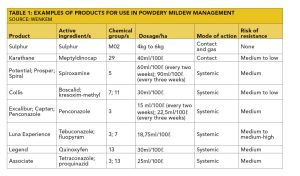

Aside from sulphur, a wide variety of products are available for the management of powdery mildew (see Table 1). Some farmers use products with the same active ingredients twice in a row; however, Rademeyer advised against this due to the risk of the fungus becoming resistant to the fungicide when an active ingredient was used repeatedly.

“There are enough products with different chemical groups to allow farmers to use a product only once a season,” he said.

“There are enough products with different chemical groups to allow farmers to use a product only once a season,” he said.

To reduce this risk, he advised farmers to use four or five products from different chemical groups, and to rotate them. He added that sulphur was a valuable weapon in this arsenal, as there was no risk of powdery mildew becoming resistant to it.

The fight

As with all pesticides, products used in the management of powdery mildew needed to be used according to the instructions in order to achieve the desired results. Thus, farmers need to read the product labels to ensure they use the correct mixtures and application methods, and apply the products under the right climatic conditions.

Rademeyer advised that it didn’t pay to spray fungicides if the spray nozzles weren’t clean or if they were worn out, as this could cause blockages or incorrect droplet sizes that could lead to poor fungicide cover. In turn, this would negatively affect the efficacy of the product.

“The nozzles have to be cleaned every morning before spraying. If the nozzles continuously clog up, the filters might break, which means they’d need to be replaced,” he added.

A nozzle of the correct size also needed to be used with the right pressure, as this will give good spray coverage and droplets of the ideal size.

Rademeyer said it was best to use four to 10 nozzles per spray pump, depending on the stage of growth and size of the canopy. “For instance, more nozzles and water are required to accommodate increased leaf coverage and vegetative growth at different phenological stages of vine development.”

He said spray droplets needed to range in size from 145 to 325 microns. “In the past, farmers were advised to spray fungicides at high pressure, which implied the use of smaller nozzles.

“We’ve since realised it’s better to use larger nozzles at lower pressure, as they don’t clog up and wear out as fast as the smaller nozzles do,” he said.

Rademeyer recommended using orange or red Albuz nozzles at a pressure range of between six and 12 bars to achieve the optimal volume of water and correct droplet size.

For good penetration of thick canopies, he advised that the fungicides be applied at a speed no faster than 80s/100m, which boils down to a maximum tractor speed of 4,5km/h to 5km/h.

Given the huge escalation in input costs, farmers might be tempted to forgo fungicide applications. To save on costs, Rademeyer said producers rather needed to apply the more expensive products early in the season, when low water volumes were required, and use the less expensive ones later, when higher volumes of water were needed.

Email Gustav Rademeyer at [email protected].