The current debate in South Africa about land expropriation without compensation has placed the spotlight on land reform policies and polarised rural communities.

On the one hand, the idea of accelerated land reform seems to have stimulated demand for land; many people imagine that obtaining land will help them emerge out of poverty.

On the other hand, others worry that a policy of expropriation without compensation will mean Zimbabwe-style land grabs, with all the dire implications such a scenario is assumed to have.

READ Land reform: Joint venture between seller and community pays off

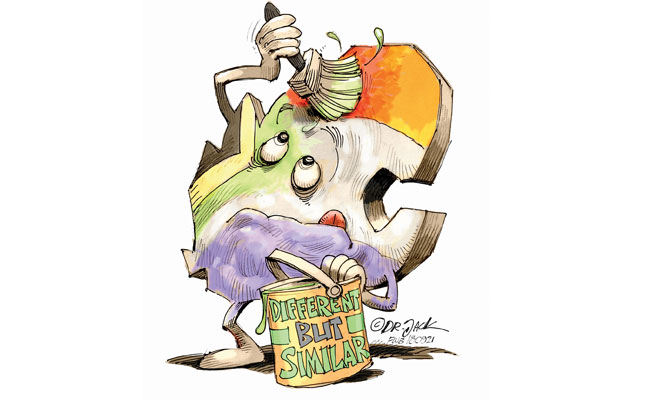

The extent to which Zimbabwe’s fast-track land reform programme holds valuable lessons for South Africa can be debated.

The purpose of this article, however, is to point out that there is a parallel closer to home that receives little attention, namely the experience of ‘homeland consolidation’.

The Tomlinson Report and expansion of the Bantustans

‘Homeland consolidation’ was the process through which the reserves (territories set aside for black South African and South West African inhabitants as part of the policy of apartheid) were expanded.

Homeland consolidation was called for by the Tomlinson Commission, which was appointed by the South African government to study the economic viability of the reserves (later Bantustans) in which the government intended to confine the black population.

According to the commission’s 1954 report, the reserves were incapable of supporting South Africa’s black population without significant enlargement and state investment; therefore, homeland consolidation was a way of improving agricultural conditions in them.

Thus, while the 1913 Natives Land Act apportioned 7% of the land to the reserves, the collective size of the Bantustans, with homeland consolidation included, eventually reached 13%.

READ ‘Government’s land reform statistics not accurate’

In practice, an equally important rationale for homeland consolidation was the apartheid government’s desire to resolve the ‘chessboard’ appearance of interspersed white and black land, which contradicted the policy of separate development (Platzky and Walker, 1985).

In the process, some of the areas acquired to enlarge the former homelands merely became dumping sites for black households who had been forcibly removed from ‘black spots’ elsewhere.

Thus, even while it involved enlarging the Bantustans, consolidation played an important role in the process of dispossession.

Despite this tainted aspect of the homeland consolidation process, the reality is that it made some commercial farmland available to black people. And it also resulted in some erstwhile farmworkers being left behind when their previous employers were bought out and forced to go.

The Ciskei case study: Difference between groups

For my master’s research, I spent time in some of the areas that became part of the Ciskei homeland through consolidation in the 1970s.

The aim of the research, which included undertaking a household survey and conducting a number of in-depth life history interviews, was to understand the experiences of three distinct groups of people: those who had worked for the previous farmer and chose to stay on the land after the farmer’s departure; those who voluntarily settled on the land; and those who came to the land involuntarily after having been forcibly removed from somewhere else.

Even today, one can discern material differences between these three groups.

For example, many of those people who were moved involuntarily own few assets, because when they were moved, they had to sell their belongings, such as livestock, at a loss.

Some of their possessions were also stolen during the relocation process.

The situation for those who moved voluntarily is quite different. Some own livestock and practise farming, and their conditions and standards of living are much better than those of the other groups.

READ Hunting traditionally with the Khomani San

When it comes to those who had worked for the previous farmer, some were left with assets, such as houses, planters and livestock, while others received nothing from their former employers.

When the white farmers were removed, the farmworkers lost their jobs and had to look for employment elsewhere. Of those who remained behind, some worked in development projects, others worked for black people, and the rest practised farming.

At that time, agriculture was thriving, but focused mainly on peasant farming. Farmers would pay a small contribution to government to provide cover for losses at their farms, as well as to buy seeds and other inputs.

A few also practised large-scale farming and were left with significant resources by the departing farmers to enable them to continue to thrive.

The leader of the former Ciskei, Lennox Sebe, was not necessarily appreciated at the time as he was viewed as being tough and strict.

However, he supported his people and encouraged agriculture in Ciskei. He visited communities to track and monitor their progress, and provided tractors that farmers could hire for a small fee.

There were factories and businesses, some still evident today, from where Ciskeian products were exported.

After Sebe’s term ended, however, the level of farming in the former Ciskei dropped significantly.

This is because there was, and is, a lack of significant support from the current government, the youth tend to shun agriculture, and there is a general lack of interest in farming by other people.

While it would seem that the process of homeland consolidation was carried out in an uncoordinated manner, without attention to the land’s continued use for agriculture, I believe that history is repeating itself.

I view the process of homeland consolidation as an antecedent for present-day land reform. About seven million hectares of land were made available to black people during the apartheid era; this is approximately the same as the area of land transferred through land reform from 1995 to 2015.

Understanding the changes in agriculture over time due to this process will help us understand the decline of agriculture while providing lessons for the current process of land reform

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

For more information, email Zimbini Coka at [email protected].