We climb these mountains and our shoes are wearing out. Every day we go to pick,” says Xhosa khat harvester, Thandi (not her real name), pointing to khat outcrops in the rugged Kei River valley between Cathcart and Bolo in the Eastern Cape. Thandi and her friends harvest khat leaves every day, producing foot-long bundles to sell to Somali traders at R15 each – a welcome income in a desperately poor communal area.

In fact, it’s easy money for these women; the only skill required is the ability to identify and find the freshest leaves and shoots. These have the highest levels of cathinone, a chemical that increases alertness and focus, and suppresses appetite. “There are many people harvesting khat,” Thandi explains, indicating the rugged river valley towards the communal lands of the former Transkei. “The Somalis come from King William’s Town at night.”

It is hardly surprising that the Somali immigrant community in the Eastern Cape has turned its attention to the khat trees of the Kei Valley. In the Horn of Africa and Yemen, khat is harvested, traded and chewed openly, in much the same way as, say, coffee is enjoyed in western homes. Similarly, khat is harvested in Kenya and exported to immigrant communities in Britain where it is legal. In the US, by contrast, possessing khat and trading in it are both illegal, as is a street drug called ‘cat‘, a synthetic form of cathinone.

The Great Kei River flows through a deep gorge from Cathcart to the Kei mouth. Large numbers of protected Catha edulis trees grow in the area.

This is also the case in South Africa, according to police spokesperson Lieutenant-Colonel Sibongile Sico. “We are intensifying our approach to dealing with drug-related crimes,” she says. “We also acknowledge that dealing with drugs is a global challenge that needs to be co-ordinated with our international counterparts.” Sico stresses that khat is classed as an organic drug in the same category as cocaine.

A legal muddle

According to Stutterheim lawyer Ian Andrews, however, the fact that Catha edulis is a protected tree presents a conundrum. “How can the Catha edulis tree be protected if possession of it is unlawful?” he asks. “You are not allowed to chop it out because it’s protected, but if you have one growing on your property, you’re contravening the law.’’

Such legislation is even more confusing in a country where Xhosa people have used khat medicinally for hundreds of years. Tombi (not her real name), who lives near King William’s Town, explains that khat has been a part of her life from an early age. “You use it when your chest is sore or when you get fever. When I was a little girl, my parents gave it to me,’’ recalls the 65-year-old. “I remember my granny sometimes cooked leaves in a pot of water outside and then strained it and poured it into cups for us to drink. It was like tea, only green with no sugar.’’

Farmers and the khat trade

Despite studies suggesting that prolonged use of khat can lead to mental health problems, farmers have always accepted the habit among Xhosa workers as part of life in the Kei River valley. “All our guys chew the stuff – it gives them energy,” says Bolo farmer Russell Bowman. “If you searched them now, you’d find they would all have leaves in their pockets.”

It seems as if the habit of chewing khat as a remedy for flu symptoms has rubbed off on at least one commercial farmer who spoke to Farmer’s Weekly.

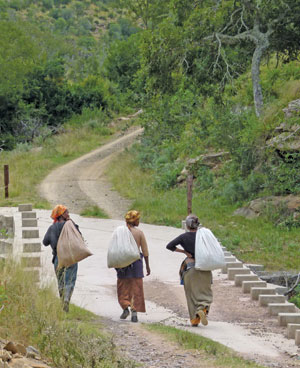

Catha edulis harvesters cross a causeway carrying their day’s harvest.

“If I feel I have the flu coming on, I grab a handful of shoots and put it into my mouth for 20 to 30 minutes and the flu simply doesn’t materialise,” says Peter (not his real name). “It’s also an appetite suppressant and gives one energy.” But even Peter admits that Somali immigrants entering the region at night in search of khat has unnerved crime-weary farmers. “Khat has never been an issue, but now that the Somalis are coming in to buy it, there’s a problem,” he says.

This is confirmed by Stutterheim-based anthropologist Dr Manton Hirst, who in the 1990s studied the use of khat in the region. According to him, the traders are not ‘criminal types’ but their zealousness to get to khat trees on commercial farms is a cause for concern. “It’s no joke,’’ he says. “If you don’t sell it to these people, they steal it from you. This is the reality of the situation.”

Crime worries

Although no major damage to property or crimes have been recorded as a result of the khat trade, farmers are concerned about the problem of trespassing. The area is extremely isolated, and is not served by police patrols or farm watches, leaving farmers feeling highly vulnerable. Cathcart farmer Andrew Bennet believes that the khat trade is a springboard for other crimes, including theft of livestock and infrastructure.

He has attempted to control the movement of Somali traders by locking a farm gate on a known smuggling route. “When we got there at six in the morning to open up, the Somalis were sitting there,’’ he says. “They said they were going to Quanti, but of course they walked over into the Kei Valley.” Hirst maintains that farmers are unlikely to stop the trade, mainly because it is beneficial to both immigrant traders and the Xhosa residents of the region.

“The Somalis have the money to bribe the farm workers to pick the khat,’’ he points out. ”So whether the farmer gives them permission to do it or not, it’s happening anyway. The farmers have no control over it.”

Successful – and secretive

The police, too, seem unable to stamp out the problem, according to Hirst. Despite numerous arrests, no successful convictions have been recorded. Their efforts have simply driven the trade underground, with Somalis no longer openly buying or selling khat. It was scarcely surprising, therefore, that when Farmer’s Weekly visited bustling King William’s Town recently in search of Somali khat traders, there was none to be found and the Somalis were wary of questions.

Eventually, Nbdala Mursal, a representative of the Somali Association of South Africa, agreed to be interviewed. He explained that it was incorrect to assume that all Somalis were somehow involved in the khat trade. “Very few Somalis in this part of the world chew it, but everybody thinks that we all do it – which is not true,” he insisted.

Sources: www.nationalgeographic.com, www.plantzafrica.com and www.erowid.org.

Contact Lieutenant- Colonel Sibongile Sico on 040 608 8400.